This post is published as part of an editorial partnership between Ranking Digital Rights and Global Voices.

When students in Bangladesh protested, demanding improved road safety, mobile internet connections were cut. Image via Wikimedia Commons by Asive Chowdhury CC: BY-SA 4.0

When students in Dhaka, Bangladesh launched public protests demanding road safety after a speeding bus killed two students on July 29, mobile internet connections suddenly were no more.

When the protests turned violent on August 3, after rumors of rape and kidnapping triggered confrontations between police and protesters, authorities resorted to shutting down 3G and 4G networks in and around Dhaka.

Local media reported that the Telecommunication Regulatory Commission ordered service providers to reduce mobile phone network signals for 24 hours so that only 2G networks could operate.

The measures made it impossible to share multimedia and live video, which many protesters were using in an effort to show what actually was happening on the streets, in real time, and to debunk false claims. Telecom operators in Bangladesh gave subscribers no explanation of the cut in service.

These measures are not unique to Bangladesh. They represent part of a growing trend across South Asia, where access to networks or platforms is restricted or completely shut down when protests or violence erupts, and the public is left in the dark, with little or no information about what causes these shutdowns.

Trends in South Asia mirror what has become an increasingly serious human rights threat around the world. Although the United Nations Human Rights Council has condemned network shutdowns and other intentional restrictions on access as violations of international human rights law, governments continue to order telecommunications companies to restrict access. Advocacy group Access Now documented 116 network shutdowns around the world between January 2016 and September 2017.

Technical glitch or strategic shutdown?

Earlier this year, Sri Lankan authorities shut down the internet in the district of Kandy, in response to acts of sectarian violence. The government, which also ordered telecom operators to block Facebook, Viber and WhatsApp across the country, blamed social media for spreading hate speech and calls to violence.

While service providers alerted users prior to the shutdowns, “there was no indication as to why in the formal notice,” Amalini De Sayrah, an editor at GroundViews, an award-winning citizen media group based in Colombo told Global Voices. GroundViews contacted the Telecommunication Regulatory Commission for more information, but “there was confusion or just unwillingness to divulge more,” De Sayrah said. “We were told it [the shutdown] would end in a few hours, but it carried on for a few days.”

The lack of corporate transparency is also an issue in India, where the Software Freedom Law Center, documented 106 shutdowns across the country so far in 2018.

In India, users are “most often” not informed about these shutdowns before they take place, “leaving [them] to wonder if it is a technical glitch or a shutdown,” Mishi Choudhary, legal director at the SFLC told Global Voices in a previous story.

“Transparency in the operator-user relation has a long way to go in South Asia,” said Subhashish Panigrahi, a Global Voices author and co-founder of O Foundation (OFDN) a non profit organization working to preserve underrepresented languages and cultures through digital technology. “India had blocked as many as 23,030 websites by 2017. There are cases where the operators share about the shutdowns and there are many [others] where the users are left to be startled.”

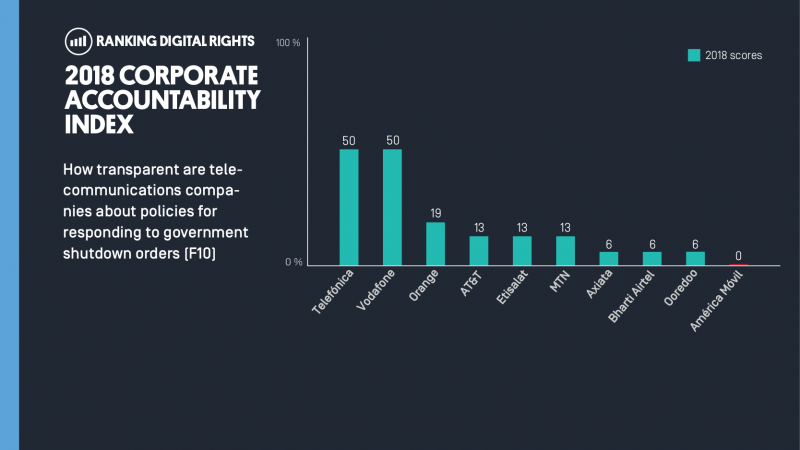

Research from the Ranking Digital Rights 2018 Corporate Accountability Index showed that the world’s most powerful telecommunication companies lack transparency about how they handle government shutdown demands. Out of ten telcos evaluated by the Index, only Vodafone clearly disclosed a process for responding to these types of government demands and clearly committed to push back against demands when possible. Telefonica was the only company that disclosed the number of shutdown requests it received. All other eight companies, including the Indian multinational telecommunication group Bharti Airtel, revealed almost nothing or no information at all.

‘Operators owe transparency to their users’

Telecommunications companies are facing increasing burdens in this area, from all sides. Companies that push back on shutdown orders can risk losing their licenses. While companies usually have little choice but to follow these orders, that should not absolve them from responsibility towards their users’ human rights.

In legally-challenging environments, companies should at least notify users when shutdowns are about to happen, name the authorities that ordered the shutdown, and specify its duration activists told Global Voices.

De Sayrah said that she would like to see operators not only publish alerts about shutdowns that are about to happen but also include information on who made the shutdown request and when and the duration of restriction.

“This way the companies are accountable to the people and are doing their part, which is one step up from the government,” she added.

Panigrahi noted that industry organizations like the Internet Service Providers Association of India’s (ISPAI), which represents 60 operators could address this issue by maintaining a public record of the ongoing shutdowns. While there are civil society groups and activists that document these restrictions, “ISPs have a wider and a direct reach to users and [can] always inform users prior to the shutdowns.” He added that activists and civil society groups “can at times put their own security at risk” in their efforts to document shutdown cases.

Transparency from the part of telcos can help media groups that play a key role in times of crisis to verify information and provide accurate media coverage prepare better. During the March shutdowns in Sri Lanka, GroundViews found it challenging to get information on the situation in Kandy, editor Raisa Wickrematunge told Global Voices.

“Providing justifications and ideally a potential duration of a block or shutdown can help assess what strategy to use to continue pushing out information,” she added.

Corporate transparency can also help digital rights activists and advocacy groups understand the scope, the impact and the legality of shutdowns.

Data such as revenue loss experienced by telcos, impact on e-commerce, reasons given by the state and terms of licensing could be useful for advocacy groups, Choudhary said.

“It is important to have a record of how long these blocks persist, and when and why they commenced, in order to help digital rights advocates prepare for possible clampdowns in the future,” Wickrematunge said. She added that transparency can be useful when engaging with the government “to try and prevent these types of shutdowns happening arbitrarily…”

Despite the outcry from civil society groups and a 2016 UN Human Rights Council resolution condemning “measures to intentionally prevent or disrupt access to or dissemination of information online,” governments across South Asia are very unlikely to stop ordering shutdowns anytime soon.

The Indian government, which has been blaming Whatsapp and other messaging and social media apps for a spike in mob killings and lynchings, has reportedly urged telecom operators “to explore various possible options” to block such applications “to protect national security.”

In Sri Lanka, activists fear that the the Kandy shutdowns may not be the last. “I do believe the incidents in March have now set a precedent for similar blocks in future, particularly on social media,” Wickrematunge said.

Following the recent 3G and 4G network shutdowns in Bangladesh, the ICT minister said that access to Facebook and networks could be restricted again for the “security of the state and its people.”

In the absence of government transparency, corporate transparency can help users and digital rights groups prepare to fight shutdowns when they are about to happen, hold to account those responsible, and raise awareness about their negative impacts.

“Operators owe complete transparency to their users, as consumers who are paying them money and also in the interest of accountability,” De Sayrah.

Companies should inform the public of how they respond to government network shutdown demands, and commit to directly notify users about these types of restrictions, and to push back on requests to shut down a network or restrict access to a service. They should also publish data about the number of shutdown requests they receive, and name the authority that ordered the shutdown, so that those responsible can be held accountable.