Images remixed by Oiwan Lam.

On June 4, which coincided with the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, a user on the Chinese microblogging platform Sina Weibo posted the word “candle’’ in Chinese. Two hours later, the post disappeared.

The post was yet another attempt by Chinese internet users to outsmart censors that ban references to the massacre that followed the 1989 student-led democracy movement in China. In the days leading to this year’s anniversary, platforms like Weibo, LINE, TOM-Skype, and others actively monitored and removed posts referencing and remembering the massacre.

Chinese companies did the same for coverage of memorial activities taking place in Hong Kong, where thousands of people joined a vigil at the city’s Victoria Park to honor the victims. For example, popular live streaming platform YY updated its list of banned keywords to include references to Hong Kong memorial activities, their locations, and names of groups and advocates organizing them.

These cases of content takedowns by Chinese social media platforms at the behest of the government are but the latest examples of how privately-owned internet companies in China are an integral part of the country’s censorship and surveillance regime. Chinese law requires local platforms, as well as foreign companies like Apple and LinkedIn doing business in the country, to proactively monitor and take down objectionable content.

Overall ranking and scores of internet and mobile ecosystem companies.

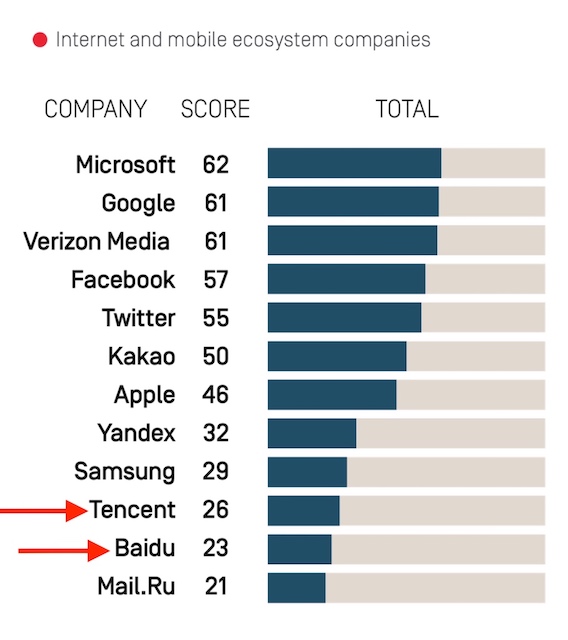

It is therefore not surprising that China’s largest tech companies Baidu and Tencent continued to perform poorly in the 2019 Ranking Digital Rights (RDR) Corporate Accountability Index. The RDR Index evaluates how transparent companies are about their policies and practices affecting human rights — specifically users’ freedom of expression and privacy.

Baidu and Tencent made notable improvements to policies and disclosures that are not directly related to government censorship and surveillance demands, like how they secure user data from breach or theft, and how they handle user information for commercial purposes. They revealed barely anything, however, about their policies and practices that pose the greatest threats to internet freedom and digital rights in China: censorship and government surveillance. Their inability to disclose commitments, policies, or practices related to government demands to take down content or provide access to user information kept Tencent and Baidu near the bottom of the 2019 RDR Index, ranking 10th and 11th respectively among the 12 internet and mobile ecosystem companies evaluated.

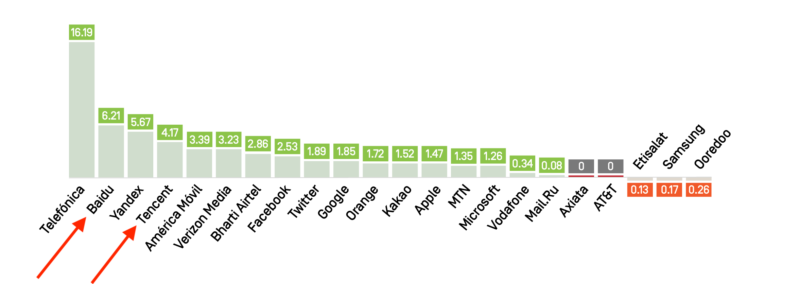

Baidu and Tencent were among the companies that improved their overall scores in the 2019 RDR Index.

Freedom of expression blackout

China’s cybersecurity law bans internet users from publishing information that damages “national honor,” “disturbs economic or social order,” or is aimed at “overthrowing the socialist system.” Platforms and search engines automatically filter politically-sensitive keywords such as “human rights’’ and “Tiananmen Square.’’ They are also required to comply with an ever-evolving list of censorship requests from authorities, driven by current events and hot topics on social media.

For example, censors last year banned phrases like “anti-sexual harassment” in an effort to prevent the #metoo movement from spreading to China. According to Wechatscope, a research initiative that monitors censorship on the Tencent-owned messaging and social media app WeChat, allegations of sexual harassment and sexual misconduct were one of the most heavily censored topics on the service in 2018.

Chinese internet companies that fail to comply with regulations risk fines or even revocation of their business license, prompting them to invest substantial financial and human resources to keep objectionable content off of their sites.

In September 2017, the Cyberspace Administration penalized Baidu, Tencent, and Weibo with maximum fines under the country’s cybersecurity laws for failing to detect and take down banned content including, “pornography’’ and “false rumors.’’ A month later, Weibo hired 1000 additional content moderators to monitor and remove “pornographic, illegal and harmful content.”

These companies are also increasingly deploying artificial intelligence technologies to help moderators monitor objectionable content.

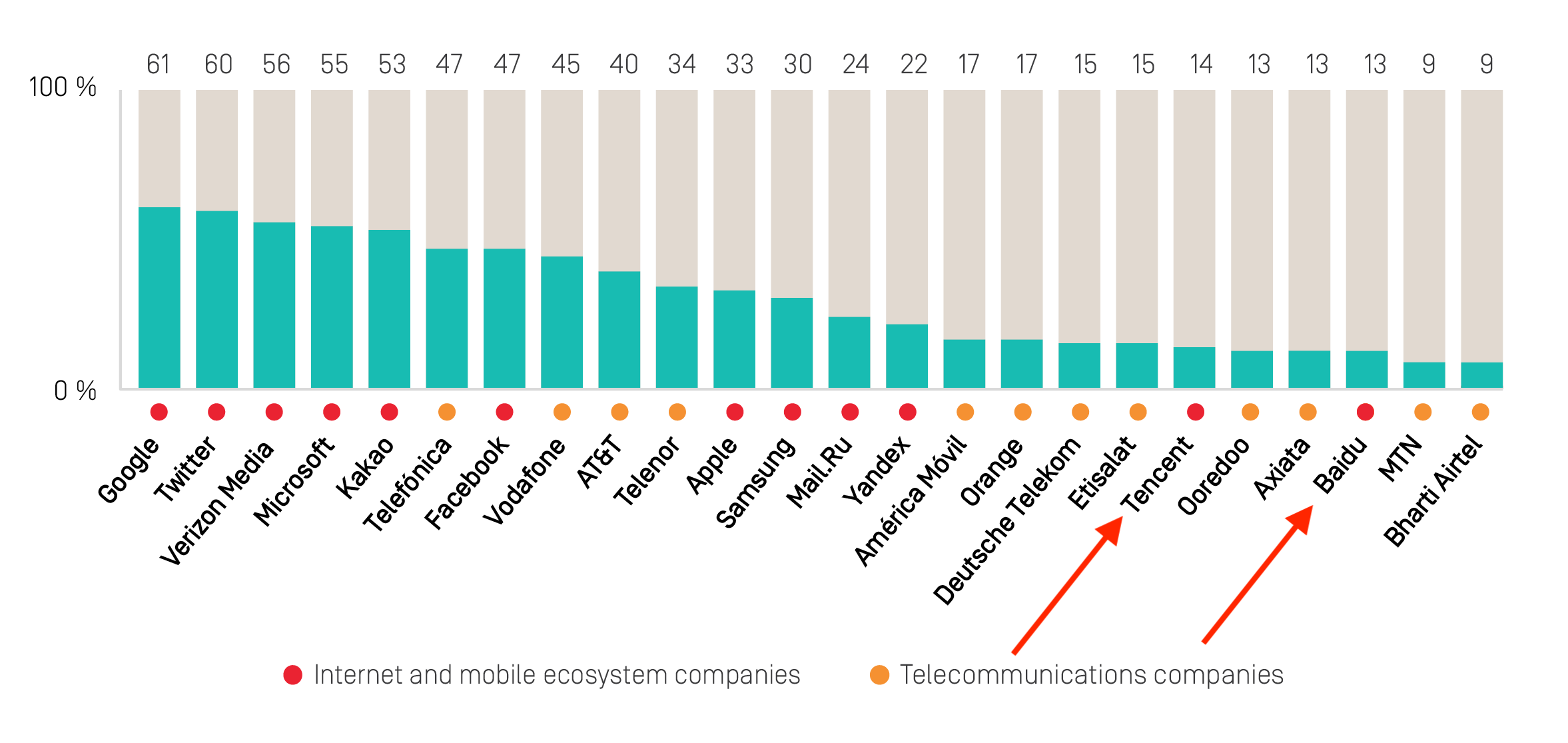

The Freedom of expression category of the RDR Index applies 11 indicators to evaluate how transparent companies are about their rules and how they are enforced, how they deal with government demands to censor content, and how they respond to government orders to shut down access to the internet or to certain services or applications. Baidu and Tencent performed poorly in this category.

The government’s constant crackdown on freedom of expression, through censorship demands and draconian laws, prevents companies from being transparent about how they moderate content on their platforms and how they respond to the Chinese government’s censorship orders. In the Freedom of Expression category of the RDR Index, Baidu and Tencent received the two lowest scores of all internet and mobile ecosystem companies, disclosing hardly anything about these policies. Both companies revealed limited information about what types of content and activities are prohibited on their services (F3) but they disclosed nothing about how they respond to government censorship demands (F5). They also did not commit to notify users when they restrict their access to content or accounts (F8).

Privacy progress remains inadequate

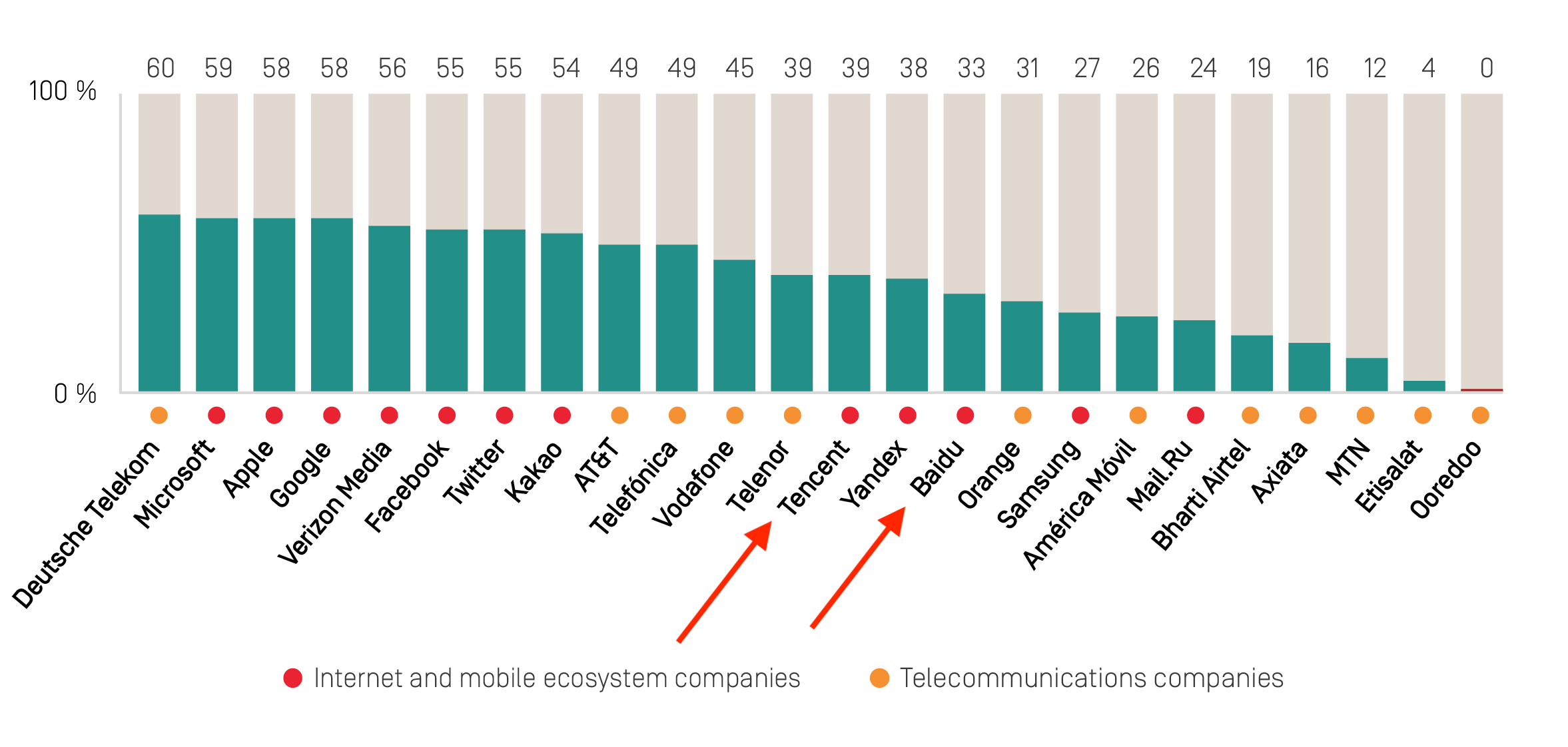

In the Privacy category, both Baidu and Tencent made improvements mainly on indicators related to how they handle user information and their security policies.

The Privacy category of the RDR Index applies 18 indicators to evaluate how transparent companies are about policies and practices affecting users’ privacy and security, including how clearly companies disclose what types of user information they collect, share, with whom, and why.

Improvements made by Baidu included disclosing more detailed information about the types of user information it shares, with whom, and why (P4, P5). The company also disclosed more about its security policies, including limits on employees’ access to user data (P13), its process for responding to data breaches (P15), and its use of encryption technologies(P16).

These positive changes appear to have been influenced by new data protection guidelines — the Personal Information Security Specification — issued by the national information technology security standards-setting organization (known as TC260), China’s national standards body. The specification clarifies the definition of personal information, and sets the guidelines for how organizations should handle personal information, including the collection, retention, use, sharing and transfer of personal data.

However, this progress remains inadequate to safeguard Chinese users’ privacy from Chinese government surveillance in a regime where political dissent can be defined as a crime and where ethnic muslims who have not been convicted of any crime are held in internment camps against their will.

China’s cybersecurity law requires internet companies to collect and verify users’ identities whenever they use major web sites or services and to “provide technical support and assistance’’ to security agencies in their criminal investigations. Internet companies are also required to keep user activity logs and relevant data for six months and to hand it over to the authorities when requested without due process.

Authorities also have direct access to user data and communications. Internet users have been arrested for the content of private conversations. WeChat has come under considerable scrutiny from activists and dissidents who believe their accounts and conversations are monitored, which the company denies. In April 2018, the internet policing department in Zhejiang Province ordered an investigation of an individual who criticized president Xi Jinping in a WeChat group that only had eight members. A leaked police directive identified the real name of the user, who used a pseudonym, phone number, ID number, and location. In 2017, several WeChat users were arrested after making politically sensitive jokes in a private chat-room.

Laws giving the Chinese government direct access to user communications prevent Baidu and Tencent from being transparent about how they handle government requests to hand over user data. Neither companies published any information at all about how they respond to third-party requests for user data (P10) and failed to reveal any data about such requests (P11). They also disclosed no commitment to notify users about requests made to access their data (P12). Baidu, however, disclosed the circumstances under which it may not notify users of requests for their information.

Opportunities for further improvement

The Chinese censorship and surveillance regime requires internet companies to play a proactive role in monitoring and removing objectionable content and surveilling users. Companies that fail to comply with government orders and regulations risk fines and even closure. As a result it is unrealistic to expect Chinese companies to commit to challenge government demands to censor content or hand over user data or to be very transparent regarding such demands. In fact, Chinese National State Security Law prevents the disclosure of information related to national security and crime investigations. However, even in the absence of regulatory changes, both Baidu and Tencent can take immediate steps to improve their disclosure of policies and practices affecting users’ freedom of expression and privacy.

Specifically, both companies could:

- Increase transparency about private requests: both companies should improve their disclosures of how they respond to private requests to restrict content or accounts and for user information.

- Give users more control over their information: Tencent and Baidu should provide users with more options to access and control their own information.

- Improve transparency regarding handling of user data for commercial purposes: the two companies could further their policies of collecting, sharing and retaining user information.