Late last year, a bombshell investigation found that 12 companies linked to the persecution of the Uyghur minority in China’s Xinjiang region appeared in Article 9 funds. These funds, under EU law, are meant to include only companies that follow the strictest level of sustainability. One of those companies was Dahua, a Chinese manufacturer of video surveillance systems. Dahua was accused by industry research group IPVM of selling products that detected the facial attributes of ethnic Uyghurs to the Chinese government. The danger of these kinds of contracts for vulnerable groups are clear—and yet, the influential sustainability ratings provider Sustainalytics still classified Dahua as “Low Risk.”

Such disconnects between companies’ ESG risk ratings and the actual risks they generate for people and societies are all too common.

ESG ratings still measure the risk that the world poses to the company and its shareholders, rather than a company’s real impact on the world.

In the U.S., right-wing politicians have co-opted valid critiques to accuse ESG investing of promoting “woke ideologies,” withdraw investments from ESG-labeled funds, and ban state pension funds from using ESG criteria to guide their decisions. This week, the conservative crusade against ESG culminated in the first presidential veto of Joe Biden’s term. Biden struck down a Republican bill that would have barred retirement funds from considering ESG factors in their investment decisions.

Beyond the loud yet shallow critiques of conservative circles lies a more legitimate debate. As Bloomberg has reported, ESG ratings still measure the risk that the world poses to the company and its shareholders, rather than a company’s real impact on the world. They are fundamentally still designed to protect profits, not people.

Consequently, for years, U.S. tech companies surfed the lucrative wave of surveillance capitalism with only a contingent of digital rights advocates standing in vocal opposition. In the absence of coherent privacy regulation and with strong public adoption, platforms grew and tech stocks soared. As interest in ESG spread, many tech companies continued to receive high scores from rating agencies, often due to their naturally low carbon footprint. This translated into limited concern from many of the world’s most powerful investors.

Yet an increasing number of revelations about the potential harms of Big Tech during the past few years has forced a rethink. Much of the investment community is now recognizing the risk of privacy-invasive business models and corporate misbehavior in the tech world. But the flaws in the fabric of ESG data risk leading investors to underestimate the next big threat to the users of tech products and those around them.

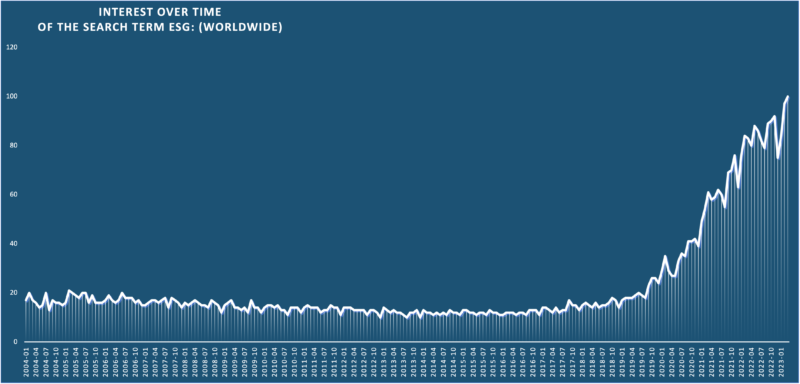

Line goes up: Google Trends line for “ESG,” Jan 2004 to Jan 2023. According to Google, “Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term.”

Rating the Raters

ESG investing, or “responsible investing,” uses environmental, social, and governance criteria to build a portfolio of “responsible” companies. If an investment fund deems a company’s performance on these issues “good enough,” its decision to invest or seek alternatives becomes a signal for others to follow suit. This continuous feedback loop has driven a steady torrent of capital toward companies and funds with an ESG label, often awarded by established financial agencies.

While ESG as a term has been around since 2004, it has seen explosive growth since the start of the pandemic. Consulting giant PwC recently estimated the volume of ESG-labeled capital at 18 trillion USD worldwide, on track to form a fifth of all investments by 2026. There are numerous powerful actors in the responsible investing community, but one group has attracted particularly intense scrutiny from policymakers, regulators, and investors themselves: ESG rating agencies.

Consulting giant PwC recently estimated the volume of ESG-labeled capital at 18 trillion USD worldwide, on track to forming a fifth of all investments by 2026.

By most accounts, the largest provider of ratings is MSCI, followed by Sustainalytics, RepRisk, and ISS, among others. These agencies evaluate how vulnerable companies are to “financially relevant ESG risks” and how well they manage those risks. But agencies do not inherently view the obligation to respect and protect human rights as “financially relevant,” unless a human rights issue exposes the company to enough financial and reputational damage through investigations, fines, and other setbacks.

Nevertheless, ESG scores from the heavyweights in the field hold enormous power to steer the conversation about what counts as “sustainable” or “ethical” in the investing world. Yet the data generated by the ESG industry is awash with problems. Paywalled scores with poorly explained drivers, disparate standards, conflicts of interest, and decisions that are sometimes at odds with reality are only some of them. For example, in February 2022, when Russian forces invaded Ukraine, MSCI immediately downgraded most Russian companies. But many others headquartered elsewhere kept their operations in Russia going and experienced no impact on their ESG scores, despite indirectly supporting a regime engaged in severe human rights violations. Why? One possibility is that they were able to mitigate any negative impact on their scores as the data providers did not consider the risk of staying in Russia “financially relevant” enough to lower their score.

Many of the largest tech firms, despite their spotty human rights records, coast to strong ESG scores simply by virtue of being less environmentally destructive than other companies.

This case illustrates some of the broader issues that pervade ESG scores:

- ESG scores are not based on any one consistent set of standards. This allows providers to freely adjust scores with no pre-existing framework to guide such decisions or account for them publicly. In one illustrative example, MSCI upgraded McDonald’s ESG rating in 2021, citing examples of good environmental stewardship that it had not previously considered in its methodology. Some of these improvements stemmed from new government regulations on recycling that the company had been compelled to abide by. The fast food chain’s emissions had in fact climbed steadily over time, generating more greenhouse gases per year than entire countries, including Hungary and Portugal. Similar cases are rampant. Many of the largest tech firms, despite their spotty human rights records, often coast to strong ESG scores simply by virtue of being less environmentally destructive than their fossil-burning corporate peers.

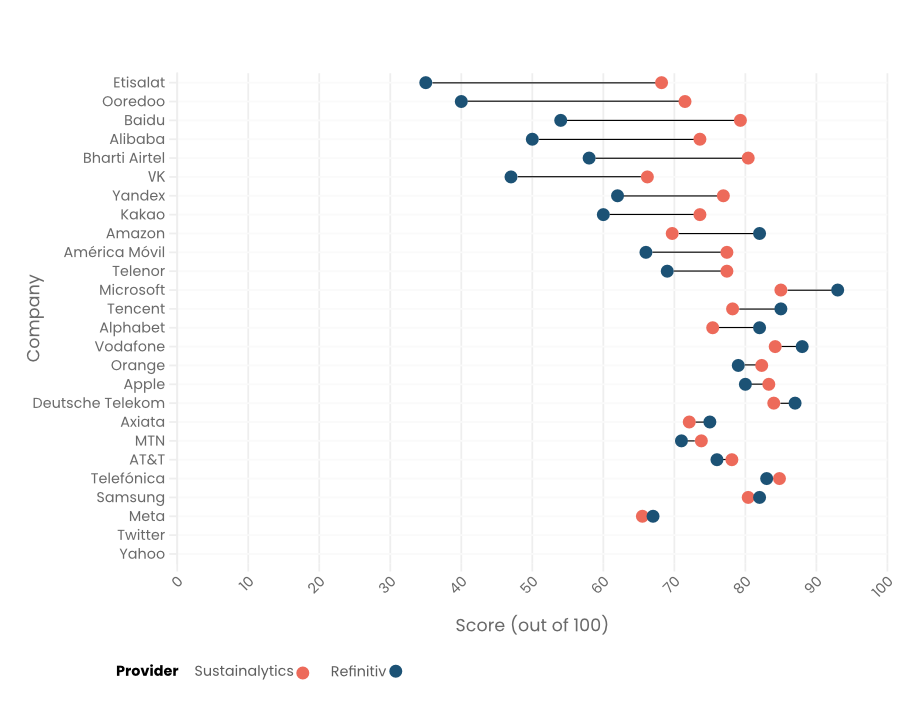

- Different ratings providers produce different results. Dahua, the China-based surveillance company deemed “Low Risk” by Sustainalytics, received the lowest possible ESG score from MSCI. A recent study of the six most prominent ESG rating agencies revealed that less than half of their scores in the “Social” category correlated across agencies. In addition, three of the six agencies have either one single human rights indicator or none at all, which implies that they are evaluating limited areas of operation and their related impacts. Thus, even when they use a human rights lens, rating agencies risk turning complex human rights issues into an oversimplified check-the-box exercise.

- The logic behind the factors that culminate in an overall ESG rating is almost never clear to the public. The mere fact that ESG ratings diverge is not inherently a red flag, but it becomes one when coupled with low public-facing transparency with regard to what is actually factored into these scores and how strong an impact each element can have. Are greenhouse gas emissions more important than protecting user privacy? Does expanding training programs for marginalized youth outweigh a record of compliance with censorship orders? Many critics of holistic ESG scores argue that topics as diverse as these should never be compared to begin with, much less assigned arbitrary weights. Balancing inherently incomparable issues across companies offering an array of services across different operating markets opens ESG ratings up to biases that are themselves hard to untangle.

- ESG scores ignore human rights issues that are vital to holding tech companies accountable. Rating providers tend to emphasize how tech companies address climate change, advance diversity and safety in the workplace, and strive for ethical supply chains. While critically important, these issues do not reflect the full spectrum of human rights problems that tech companies can generate. Investors will not find information about an e-commerce behemoth’s efforts to enforce its rules on hate speech, its resistance to government censorship demands, or the protections it puts in place to curb discriminatory ad targeting. Some providers may acknowledge the “financial relevance” of privacy and data security for tech platforms, only to assign low weight to their broader digital rights policies. This means ESG rating agencies and the investors who rely on them may be severely underestimating a number of real “non-financial” risks, especially in rapidly evolving industries.

- Conflicts of interest abound. Some rating firms provide paid consulting services for the very companies they rate. They also face strong pressure from various lobbying groups, which sometimes succeed in bending their standards away from proper scrutiny on human rights issues.

The Gap Non-Profit Benchmarks Fill

Human rights benchmarks, and the broader ecosystem of similar civil society-led tools, take a different approach than the one championed by commercial rating agencies. Protecting companies’ bottom line is not our goal. Rather, our goal is to hold companies accountable for how well they manage the protection of fundamental rights⸺in RDR’s case, freedom of expression and privacy.

Putting the focus on companies’ impact on people over profits makes a difference. For RDR, it gives our data a stable anchoring point that ESG ratings generally lack: international human rights standards. These standards should be the real baseline that all companies strive for. Grounding ESG ratings in such frameworks would strengthen their foundations and give them more credibility. But it would also help address other issues that reduce the value of ESG ratings, including inconsistency, poor transparency, and low granularity.

ESG rating agencies and the investors who rely on them may be severely underestimating a number of real non-financial risks.

Benchmarks like RDR also fulfill an essential function currently missing in the ESG space: they highlight companies’ impact on rights that have often been neglected by existing ESG frameworks. For example, RDR analyzes how companies help enable or suppress speech, what they do with users’ data, and what governance structures oversee it all. While elements of these themes exist in some commercial ratings, they compete with many other metrics and struggle for visibility among them. This dilutes the importance of the serious human rights issues they represent.

Since we developed our inaugural Corporate Accountability Index with Sustainalytics a decade ago, one of our main objectives has been to bridge the divide between digital rights groups and investors looking to hold companies to account. We take the core issues activists are actually fighting for and evaluate how transparent tech corporations are about them, using the benchmarking tools that shareholders are already familiar with. As we’ve evolved, we’ve held firmly to the principle of listening to civil society groups, developing our standards to reflect their voice and their warnings about emerging human rights issues in tech. ESG rating agencies could learn a great deal from open and equitable consultation with activists on the front lines, which is familiar territory for civil society-led benchmarks.

The impact that benchmarks like RDR have achieved can provide important lessons for ESG rating agencies that want to measure the risk companies pose to individuals and society, not just the bottom line:

- Apply established frameworks to assessments of corporate responsibility, with a special emphasis on human rights frameworks. In contrast with ESG providers, RDR and other benchmarks use an array of both industry-specific and broader human rights frameworks as the bedrock of our methodology. Indeed, many of RDR’s indicators draw on the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights. But we also use the Global Network Initiative’s Implementation Guidelines (e.g., to assess due diligence processes), the Council of Europe’s guidelines on human rights and algorithms (to assess AI policies), and the Santa Clara Principles (to assess transparency on content governance).

- Be transparent about results and how scores are calculated. At RDR, all of our findings are public, and we believe this should be the norm. This means every explanation of each company’s result on every one of the 58 indicators and 325 questions that make up a company’s final score is freely available. We do not assign special weights to any specific topic in calculating companies’ scores, preferring instead to give our civil society partners around the world the flexibility to do so according to their needs.

- Ask companies for explicit answers to detailed questions. ESG criteria need to be granular enough to be informative, roughly comparable, and not susceptible to giving companies a free pass. The bird’s-eye view most ESG standards provide to the public is insufficient. Many companies, including tech giants, offer a range of services that each carry their own specific risks. For example, YouTube and the Play Store both belong to Google, but the risks that come with them overlap in as many ways as they diverge. RDR’s approach recognizes these modularities by evaluating the individual products or services that the company offers, while also assessing the company as a whole on governance questions that are relevant across all operations. Stringent criteria minimize the chances that a company will rack up points for vague declarations of new but badly deficient policies.

- Understand how companies’ operations affect the majority world. Civil society benchmarks, including ours, often assess how transparent a company is in its home market. But tech and telecom titans operate internationally, and their impacts vary according to local and regional realities. When corporations brush off their responsibilities in “non-priority markets,” the consequences for human rights can be dire. This is why standard setters have to apply strong scrutiny to countries outside of a company’s “core” operating environment. RDR strives to achieve this goal by providing direct guidance to human rights groups in dozens of countries, assisting them in tailoring our approach to their specific needs. The result is a fast-growing series of adaptations led by our partners that reflect their assessment of corporate accountability in their countries and fields of expertise. This creates new centers of power in advocacy, helping to decolonize the field and bring more equity to it.

Looking Beyond

Benchmarks like RDR are able to offer what ESG ratings do not because of a clear and direct focus on societal impacts. This allows us to focus on the risks that tech companies and their technologies pose to the user and those around them rather than on how the world affects companies’ valuation. Non-profit benchmarks provide insight that ESG ratings do not always cover. Our strong commitment to human rights is shared by many civil society groups and translates into robust corporate accountability standards. While all benchmarks have their share of challenges and dilemmas, those produced by civil society fill essential gaps in the current ESG landscape.

There is broad agreement that ESG has entered an era of reckoning that represents the next stage of its maturity. The new battles will be fought not around whether investors should consider ESG factors, but what those factors should look like and what established laws and norms they seek to advance.

Anything short of strong human rights and transparency standards in ESG will fail to ensure proper corporate accountability.

Regulators and legislators have not been blind to the power of ESG rating agencies. The EU has adopted several landmark regulations on sustainable finance, and its 2022 consultation on ESG rating providers found overwhelming support for more transparency and stronger regulation. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is also working on stricter, more standardized transparency standards for ESG-labeled funds, tackling environmental factors first. Rating providers themselves are slowly starting to lean on human rights principles, as Sustainalytics did late last year when it downgraded three of China’s tech giants for conceding to censorship demands.

We know where RDR stands: Anything short of strong human rights and transparency standards will fail to ensure proper corporate accountability. This year we are once again actively partnering with investors to bring human rights issues to the table at companies like Amazon, Google, and Meta through shareholder proposals at their annual meetings. Actions like this allow us to help shape the reality of business and human rights that we want to see rather than simply reporting on it. And they symbolize how we envision the evolution of benchmarking in the months and years to come: as a proactive, inclusive, collaborative movement to hold companies to account, grounded in the highest global standards. We hope that, as the ESG data community confronts the challenges of its evolution, it will move closer to embracing such an ethos.