Apple made headlines in September 2020 with the launch of its first-ever explicit commitment to uphold human rights across its operations, from policies for users to its hardware supply chain. This was big news, especially coming from the most valuable publicly traded company in the world. But it was not a coincidence.

In 2019, amid mass unrest and a violent crackdown against protesters in Hong Kong, hundreds of apps—including apps for the New York Times, Quartz, and a Hong Kong protest-mapping app—were censored from the App Store, with little explanation from the company, and no indication of what policies actually governed these decisions. In spite of widespread media coverage of Apple’s censorship and strong condemnation from civil society, the company made no real changes to its policies or operations.

But in early 2020, Apple shareholders came together (with the help of SumOfUs) and put forth a resolution—citing RDR’s 2019 data—that would have required Apple’s board of directors to report annually on the company’s policies on freedom of expression and access to information. The measure was defeated but received more than 40 percent of votes cast, effectively putting the company on notice. All told, these forces—big public reactions to censorship, civil society advocacy, and shareholder pressure—came together and pushed Apple to change its ways. Just a few months later, Apple’s first-ever human rights policy was published for all to see.

The pillars of shareholder activism

Scores of people and organizations, from individual “retail” investors to retirement funds, invest in the Big Tech companies. Of course, some investors are mainly focused on profits, but we know that many of them care deeply about the effects of these companies on the public interest, and they actively challenge companies to behave more responsibly. These initiatives are often anchored in a rapidly evolving universe of ESG (environmental, social, and governance) frameworks. A growing chorus of experts argues that human rights should be the bedrock of those frameworks.

When a company goes public, anyone can opt to buy shares of that company. This enables the investor to reap dividends from the company’s profits, but it also gives them a stake in key decisions about how the company is managed, from appointing directors to selling off its assets. Shareholders can propose resolutions on anything from the right to repair your device to the human rights impacts of working with repressive regimes, and then vote on them at a company’s annual general meeting. Such resolutions are a key pillar of shareholder activism—the ensemble of strategies shareholders use to exert pressure on management.

The votes of Apple shareholders in the push for a company-wide commitment to human rights are just one example of how this kind of power can make a difference. Sustained pressure from investors continues to elicit major commitments and disclosures from companies, and it is gaining more traction than ever. As of last month, members of an influential coalition of shareholders had filed 436 shareholder resolutions (proposals) targeting companies—a stratospheric leap over the 244 filed at the same time last year.

In the U.S., however, a combination of unfair and lax regulations at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which was established to “maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets,” and oversees the public sale of company stock shares, has tipped the balance of power against ordinary shareholders in recent years.

The SEC has overseen a proliferation of companies that have deliberately diluted (or eliminated, in some cases) shareholders’ voting rights. Rather than adhering to the standard of issuing one vote per share, they have created systems known as dual- or multi-class share structures, in which a special type of share—that only company insiders can own—is worth 10, 20, or even 50 votes. Multi-class share structures can entrench irresponsible management, kill leadership’s incentives to talk to (and answer) the public, and crush investor votes for change.

The agency also has maintained a set of rules adopted in late 2020 that limit (and sometimes eliminate) shareholders’ ability to participate in actions that determine the future of the company.

Company executives have thus imbued themselves with power and immunity from standard corporate accountability mechanisms at a rate previously unseen in any industry, and they faced little regulatory pushback along the way.

Let’s put power back into the hands of ordinary shareholders

In order to give people a true stake in the companies where they hold shares, we must abolish the systemic forces that have allowed companies to amass power at the top.

This year at RDR, we will be pressuring U.S. policymakers to:

- End multi-class share structures. Congress must mandate that companies with existing unequal voting structures adopt sunset provisions, and that newly public companies be barred from offering non-voting share classes entirely. Until these structures are fully abolished, companies that maintain them should be required to publicly disclose the disparity between ownership and voting power.

- Repeal rules that hinder shareholder action on human rights. The SEC must rescind rules passed during the Trump administration that undermine shareholder ability to file and vote on proposals and limit shareholder ability to build coalitions.

One share, one vote? Not anymore.

Our campaign will focus on two key issues: multi-class share structures and the special set of rules that came into force at the SEC in the final months of the Trump presidency.

In the case of multi-class share structures, the premise is simple: When a company goes public, it can create two or more classes of shareholders, each with different voting rights. One class (often called “Class A”) may allocate one vote per share, while another class (often called “Class B”) may assign 10, 20, or more votes per share. In scenarios like this, Class B shareholders have more power per share that they can exercise at the company’s annual general meeting. In the absence of regulation, companies create multiple classes of shares to ensure that those in control at the initial public offering (IPO)—the founders and early employees in particular—can stay in control for the long term, or as long as they want.

With multi-class structures in place, founders and insiders effectively become a superclass, granting themselves many times the voting power of the ordinary shareholder, and often controlling the outcome of a vote, despite owning a relatively small volume of their own company’s stock. The rules around the superclass shares are encoded in the terms of the company’s IPO. In the vast majority of cases, those terms say that superclass shares cannot be sold to the public. They are an exclusive good that can only benefit company insiders.

While one vote belonging to the superclass is usually worth 10 “ordinary” votes, 20-to-1 voting control is becoming a new normal for companies that have gone public in recent years, such as Airbnb and Lyft. For some companies, such as Alphabet (Google) and Dropbox, the lowest class does not get to vote at all.

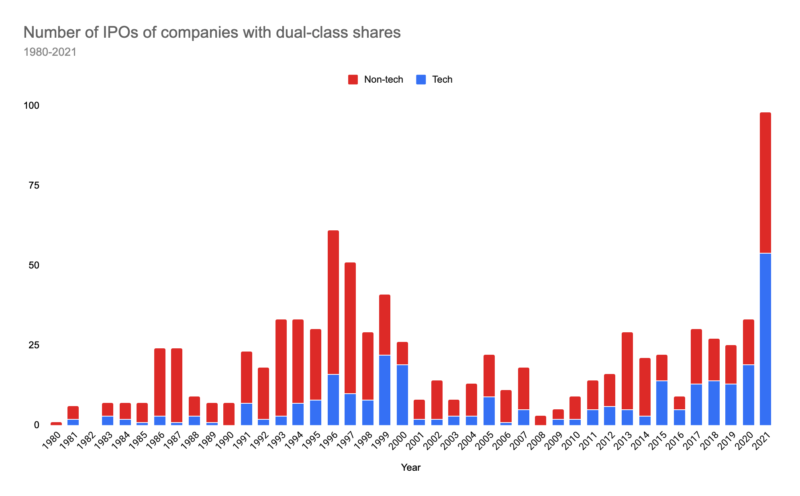

Why do such blatantly lopsided structures exist—and how do companies get away with imposing them? A common belief holds that so-called visionary CEOs and their associates should be left to play in their sandbox and maximize innovation without interference from activist shareholders. In the tech world, Google (now Alphabet) ushered in the era of skewed voting rights when it went public in 2004. Chinese e-commerce juggernaut Alibaba debuted on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) a decade later with the largest tech IPO in history (a record it still holds) and a dual-class structure. In 2012, Facebook (now Meta) went public with 57 percent of the voting power in the hands of CEO Mark Zuckerberg, where it remains today. In 2021, one-third of all newly public companies in the U.S. adopted multi-class structures—a massive surge that capped off years of incremental growth.

The impact of insiders’ votes comes out in vivid detail when we look at the support a resolution received compared to the support it would have received if the superclass had not held total vote control. At Meta, for instance, four of the six proposals that made it to the ballot in 2021 would have received a majority were it not for Zuckerberg’s veto. Shareholders have proposed to scrap the dual-class structure every year since 2014. In 2021, without Zuckerberg’s votes, this resolution would have netted 90 percent support.

Then there’s the “wedge” issue. Because insiders want to maximize control while minimizing their own investment, they often seek to own as few shares as will give them majority voting power. The greater the disparity—or wedge—between how much of the company the voting superclass owns and how much voting power it wields, the more severe the impact on ordinary shareholders. Shares with no voting rights, which exist at approximately one-fifth of all multi-class companies listed in the U.S., only drive that wedge deeper.

| Company | IPO | Exchange | Superclass votes | Ordinary class votes | Sunset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alibaba | 2014 | NYSE | 8 | 1 | Never |

| Alphabet (Google) | 2004 | NASDAQ | 10 | 1/0* | Never |

| Dropbox | 2018 | NASDAQ | 10 | 1/0* | Never |

| Groupon | 2011 | NASDAQ | 150 | 1 | 2016 |

| Lyft | 2019 | NASDAQ | 20 | 1 | Never |

| Meta (Facebook) | 2012 | NASDAQ | 10 | 1 | Never |

| Palantir*** | 2020 | NYSE | 10 | 1 | Never |

| 2019 | NYSE | 20 | 1 | Never | |

| Roblox*** | 2021 | NYSE | 20 | 1 | 2036 |

| Snap | 2017 | NYSE | 10 | 0** | Never |

| Zoom | 2019 | NASDAQ | 10 | 1 | 2034 |

* Alphabet and Dropbox have one class with a single vote per share and one with no voting rights, in addition to the superclass.

** Snap retains a class of stock that is reserved for executives and early pre-IPO investors and comes with one vote apiece. A third class—and the only one available to the public—provides shareholders with no voting rights at all.

*** Palantir and Roblox went public by holding a direct listing of stock rather than an IPO. This means that no intermediaries were involved in the process.

For example, Snap debuted on the NYSE in 2017 with nearly all of its voting power in the hands of its two co-founders and none of it afforded to ordinary shareholders. This unprecedented maneuver effectively deprived its user base—which has since nearly doubled to 319 million—of any meaningful shareholder action on their behalf1 . Snap’s intricate system of provisions in its IPO additionally allows its two co-founders to reduce their ownership to 1.4 percent each without relinquishing voting control. Another example is Palantir, whose contracts with U.S. immigration agencies have been linked to a raft of human rights harms. It gave its key executives nearly unlimited voting power as well as the ability to adjust it at will. Current rules dictate that Palantir will have this structure in place until all three of its founders have died.

In young companies, multi-class structures make it easy for leadership to innovate and grow—essentially, to “move fast and break things” without paying the damages. But this can also enable them to eschew calls to assess human rights harms that stem from their business models. If those business models are inherently toxic (say, predicated on minimizing oversight and maximizing engagement at all costs), the harms they fuel may only reveal themselves down the road, with no guarantee that the company will be able to rein them in. In mature companies, multi-class structures keep leadership’s grip on power unassailable, even when the business has long since passed the startup stage.

This is a global problem

The entrenchment of power among corporate elites through dual-class stock structures is hardly exclusive to the U.S. In 2018, tech firms flocked to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX) when it abandoned its long-standing policy of enforcing one share, one vote. This came the year after Alibaba snubbed the HKEX, precisely due to this policy. Exchanges from Brazil to Switzerland are adopting permissive dual-class provisions that favor founders. Indonesia and the United Kingdom are continuing to relax their own rules, all in a bid to attract capital that might otherwise wander off to greener pastures.

The downstream impact of unequal voting structures on users and communities will get worse in the absence of global awareness among civil society groups. If spurned in one jurisdiction, founders will gravitate toward lax regulatory systems elsewhere. Wherever regulators are preparing welcome mats for such structures, civil society organizations operating on the national level should sound the alarm.

Institutional investors are pushing back too

Within the investor community, there is momentum to change these permissive rules.

Take ISS and Glass Lewis, by far the two most dominant proxy advisory firms in the U.S2. For many shareholders, the policy recommendations issued by these firms help them decide whether to accept or reject a proposal. Since November 2021, both have taken a much more assertive stance against unequal voting rights3. BlackRock and Vanguard, the two largest asset managers in the world, have also spoken out against these practices. S&P and FTSE Russell, two of the world’s largest stock indexes, have excluded companies with low or no voting rights since 2017. Exclusion of a company’s shares from indices such as these can decrease demand for the stock, potentially lowering its price.

“…dual-class structures are a net negative because they disenfranchise shareholders and shift an unreasonable amount of risk onto the public, both of which are hallmarks of poor corporate governance.”

These major players all followed the same reasoning in adopting this approach: dual-class structures are a net negative because they disenfranchise shareholders and shift an unreasonable amount of risk onto the public, both of which are hallmarks of poor corporate governance. Even from a purely financial standpoint, there is credible evidence that any gains in value that such voting configurations may offer decay over time, while the risks reach ever greater heights.

Such changes signal that the shareholder community is approaching unanimous opposition to skewed voting structures. Yet companies are pushing harder than ever in the opposite direction, exploiting lax regulation for extra leverage.

Current regulations marginalize small shareholders

The regulatory environment in the U.S. has made it easy for industry leaders to keep putting profits ahead of the public interest. The Trump administration’s war on accountability and its zealous pursuit of deregulation proved to be a boon for corporate giants. A package of restrictive rules adopted by the SEC in September 2020 overturned decades of precedent, stifling shareholder participation in the process of filing proposals and securing support for them in three important ways:

- Stock ownership: Shareholders seeking to file a resolution for any company’s annual meeting must now own at least $25,000 in stock for one year in order to file it. This is an increase of more than 1,000 percent over the previous rule. Investors with smaller holdings must wait for up to three years before they can submit a proposal. SEC Commissioner Allison Lee has pointed out that the typical small investor would now have to bet their entire portfolio on one company in order to enjoy the same rights to participate in decision-making as large asset managers do. The SEC’s own calculations indicate the rule could have excluded more than half of the proposals submitted in 2018 had it been in force then.

- Coalition building: Shareholders are prohibited from pooling their holdings to meet the minimum threshold amount. Now, each filer and co-filer must meet the threshold independently. They are also limited to leading a single proposal per company per year. This further marginalizes everyday shareholders who seek a say in a company’s governance, especially when combined with the new restrictions on stock ownership.

- Resubmission thresholds: Shareholder resolutions must now win 5 percent of the votes in the year they are submitted, 15 percent in the second year, and 25 percent in the third year in order to stay on the ballot. The previous thresholds were 3 percent, 6 percent, and 10 percent. These revised bounds make it harder to build momentum around a human rights issue whose impact becomes apparent over time. If it takes more than a few years for people to recognize the gravity of a problem, it can be very difficult to keep it on the ballot.4

All three rules are a victory for companies, which have long lobbied legislators and regulators to “streamline” the process by getting as many proposals tossed out as possible. Lobbying groups such as the Business Roundtable and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce have sung the praises of the new amendments, which protect their interests. The adoption of the rules capped off years of pressure from industry lobbyists that spanned multiple administrations.

In a landscape where investors already vote in line with the company’s desires more than 90 percent of the time, these amendments are only tightening Big Tech’s grip on power. For their part, shareholders have overwhelmingly repudiated the rules, dragging the SEC to court over them last year in the process.

Taken together, unequal voting rights and rules that erode shareholders’ power to provoke change can reinforce each other, allowing companies to shrug off even overwhelmingly popular petitions. In the case of Meta, for example, even if 80 percent of shareholders support a resolution, it will likely fail unless Mark Zuckerberg approves. With a single “nay,” Zuckerberg can control the outcome, leaving the proposal to fall below the threshold for resubmission, and allowing leadership to escape accountability and keep the proposal off the ballot for years. The marriage of a warped voting structure and a set of rules that undercut small shareholder participation lays the groundwork for a range of harmful scenarios that hit proposals on human rights especially hard.

It’s time to call for change

Shareholders are essential allies in civil society’s efforts to hold companies accountable. But effective coalitions are hard to build when the rules favor the powerful. Unequal voting structures and stringent procedural requirements undercut the mission of human rights organizations by keeping the causes they fight for out of sight for both shareholders and company leadership.

Human rights groups that rarely work with investors must join the push to dismantle these barriers to shareholder advocacy. The first step is to embrace a set of demands that will empower shareholders, especially ESG investors, to keep the heat on current and future tech giants. The next is to call on financial regulators and lawmakers to adopt and enforce them.

This year, our focus will be on these key policy positions:

- End multi-class share structures. Unequal voting structures disenfranchise shareholders, hitting those who call for action on human rights especially hard. While eradicating such structures through federal legislation should be our ultimate objective, there are interim milestones that will bring us closer to that goal. Companies should be required to:

- Adopt sunset provisions by default. Terminating skewed voting after a honeymoon period is a permissive approach to the problem, but it would be a first step toward correcting unaccountable governance structures. The Council of Institutional Investors recommends that companies eliminate their unequal voting structures within seven years. Others argue for insiders to be forced to yield power gradually. Any of these would be an improvement.

-

- Abandon non-voting share classes. Common shares that come with no voting rights represent a parody of democratic governance. Snap, Alphabet, and other players have maintained them at the expense of shareholders’ rights. Banning non-voting share classes is a critical step toward restoring them.

-

- Disclose the wedge between ownership and voting power. Requiring clear, accessible data—total percentage of equity owned and total percentage of voting rights—can help shareholders, civil society organizations, and the public understand how much power corporate elites truly hold. Insiders should also disclose how low their ownership stake can get before they are forced to hand over the reins.

- Repeal rules that hinder shareholder action on human rights. The 2020 SEC rules changes continue to squeeze small stockholders and bury important proposals. The SEC must rescind its rules that restrict participation according to stock ownership (which marginalize small shareholders), raise the thresholds of support needed for shareholders to resubmit proposals, and limit shareholders’ ability to build coalitions.

These objectives provide a template for how to break the grip on the vote enjoyed by unaccountable leaders and compel them to address human rights issues head-on. But they will not amount to much in the absence of regulation. In the U.S., draft bills aiming to phase out multi-class stock structures are trickling in, reflecting the growing consensus that Congress can regulate what the SEC will not. Under the Biden administration, the SEC itself has already rolled back some of the most destructive SEC rules changes, but it needs to finish the job.5

The forces that are pushing for founder-friendly formulas to become an endemic part of the tech landscape are growing vigorously. As members of civil society whose paramount goal is to safeguard human rights, we have to spot where and how unaccountable governance and skewed corporate priorities end up harming people—and dismantle the structures that make this possible.