Image by Jayanti Devi via Pixahive. CC0

This is the RADAR, Ranking Digital Rights’ newsletter. This special edition was sent on July 14, 2021. Subscribe here to get The RADAR by email.

This spring, we’ve had our eyes on TikTok. Today, we’re releasing our first-ever evaluation of TikTok, Douyin (its counterpart in China), and their parent company ByteDance.

Despite politicians’ fears that it might put people’s data at risk of surveillance by Chinese authorities, TikTok’s popularity in the U.S. has skyrocketed over the past two years, bringing users a deluge of pop dance videos, comic impersonations, silly stunts involving pets and snack foods, and plenty of sponsored content.

But critics—many of whom are TikTok creators themselves—are asking poignant questions about the technology and the policies driving all this, and much more, on the app. In June, Black TikTok creators mobilized a strike, highlighting the app’s well-established tendency to promote videos of white users imitating dances choreographed by Black creators. Leaders of the strike highlighted the fact that white influencers—and the company itself—were profiting off of these videos, often without compensating or even crediting the dances’ originators.

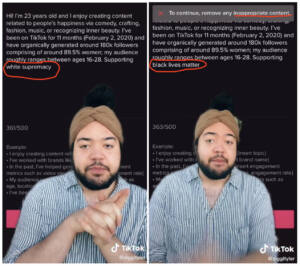

Just last week, Black TikTok creator Ziggi Tyler posted a series of videos in which he showed how the platform’s creator marketplace rejected text that contained phrases like “black lives matter,” “black success,” and “black voices” while allowing phrases like “white voices” and “white supremacy.”

@ZiggiTyler shared a screencast of his attempts to type his bio on TikTok’s Creator Marketplace. In the frame on the right, the phrase “black lives matter” triggered the warning above: “To continue, remove any inappropriate content.”

When a reporter for Vox’s Recode blog asked TikTok about the problem, a company spokesperson cited a technical error stemming from the platform’s hate speech detection systems, and stated that “Black Lives Matter does not violate our policies.” Similar to other Big Tech companies, TikTok appears to be relying on its technical systems to make big decisions about things as complex as hate speech. But Tyler’s experience proves that the machines can’t handle it.

These creators are collectively spotlighting the fact that users (and the public in general) have little ability to hold TikTok accountable for everything from curatorial choices to algorithmic bias, thanks to the company’s lack of transparency about its algorithms and content policies and processes. This is a problem, especially for an app like TikTok, where creators form the backbone of its commercial success. And as the company’s popularity and user base continue to grow, so do its effects on people’s rights and the public interest.

Intrigued by these and other questions about the policies and practices of both TikTok and its China-based counterpart, Douyin, the team at Ranking Digital Rights decided to assess both apps, alongside ByteDance, their Beijing-based parent company. We were also naturally curious about ByteDance, which is the first Chinese social media company to achieve mass popularity outside the east Asian market, and to compete with major U.S. platforms like Instagram.

With this study, we used a subset of our human rights-based standards to assess how ByteDance’s policies set the tone for both platforms, to better understand how the internet governance practices of China-based companies change or persist when companies are operating outside of Chinese territory. We also sought to find out how TikTok’s policies for U.S. users compare with the policies of its dominant U.S.-based competitors.

Our results offer a complex picture. TikTok gave users some information about how it treats their speech and data—but not nearly enough. When we compared TikTok with Douyin, its Chinese counterpart, we saw critical differences in their policies, reflecting the legal and regulatory frameworks where the two services operate. But we also saw evidence of TikTok leveraging an aggressive combination of human and algorithmic content curation and moderation techniques prioritizing content that is entertaining and apolitical, similar to Douyin and other Chinese social media platforms.

Finally, on the hot topic of U.S. users’ data security, TikTok’s policies offer the same kinds of protections for user data as its U.S. competitors, and technical research by the Citizen Lab suggests that the company takes technical precautions similar to those of U.S. platforms in its efforts to protect user data. TikTok also says that U.S. user data is stored in the U.S. (with a backup in Singapore) and is at no risk of acquisition by the Chinese government. But we have little capacity to independently test or assess the company’s claims. So we have to take TikTok’s word for it.

We’re eager to talk about our findings and insights with our RADAR readers. Read the full study, download our dataset, and tell us what you think!