Key Findings

Most companies improved scores in at least one area, and many made significant improvements in the past year. Yet companies still fell short.

Unremarkable privacy scores could signal growth in telco-enabled surveillance

By Nathalie Maréchal and Jie Zhang

Telcos enable major privacy violations, and can facilitate government surveillance, yet they say little about how they protect users from these risks.

Telcos provide the basic infrastructure of our daily communications. They are privy to our most intimate communications and, therefore, are well placed to enable major violations of our right to privacy. With a mobile phone in (nearly) every pocket, telecommunication companies are the gatekeepers to unnervingly specific details about our daily lives including our location, SMS messages, web browsing history, and app usage. But today’s global privacy debate, which has led to public and media scrutiny as well as laws like Europe’s GDPR and the U.S.’s proposed ADPPA, tends to focus on social media platforms while giving telcos a pass.

Despite also collecting massive amounts of personal data, telcos are even less transparent than Big Tech companies when it comes to disclosing what privacy policies and practices they have in place. And overly lax security practices increase the risk that user data will be accessed inappropriately. Meanwhile, privacy-invasive practices, including the collection of data for surveillance advertising and for sale to data brokers—which aggregate information from a variety of sources before selling—are rampant and expose users to commercial and even state surveillance.

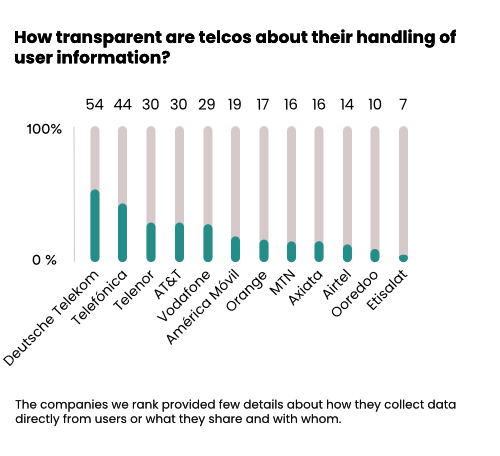

Telecommunication companies ignore users’ privacy rights in myriad ways. To begin with, companies show a systemic disregard for users’ right to know about how their data is handled. The companies we rank provided few details about how they collect data directly from users or what they share and with whom. They also disclosed very little, or in some cases nothing at all, about how they collect user information via third parties, such as from data brokers or financial institutions (often for credit scores). Although several telcos engage in targeted advertising, building user profiles based on inferred data, eight companies failed to share any information about what data they infer.

Moreover, telcos we rank also provided limited options for users to control the use of their personal data. Four companies shared no information at all. Most of the companies we rank displayed targeted advertisements to users by default. Germany’s Deutsche Telekom was the only company that did not, though this did not extend to its U.S. subsidiary, T-Mobile.

The privacy risks users face are exacerbated by a lack of attention to security. Though all ranked companies disclosed the existence of some sort of security oversight system, only Deutsche Telekom fully met RDR’s standards by disclosing that it limited employee access to user information and conducted regular internal and external security audits. Security vulnerabilities can lead to tremendous losses for both businesses and individual users when personal information is compromised.

In 2021, about 1.3 million Telenor voicemail customers were affected by a data breach. Despite such incidents, five companies, including Telenor, did not disclose whether they have a mechanism for reporting vulnerabilities.

In September, Optus, Australia’s second-largest telecom operator, faced a ransom attack from hackers who demanded that the company pay $1 million to prevent the sale of sensitive customer data of up to 10 million customers. Australian politicians blamed a lack of regulation of the telecom sector for inadequate security policies leading to the breach. In 2021, about 1.3 million subscribers were affected by a data breach incident involving Telenor’s voicemail service. Despite these kinds of incidents, five companies, including Telenor, did not disclose whether they have a mechanism through which researchers can report vulnerabilities. Half of the telcos we rank provided no information at all about how they handle potential data breaches.

The lack of privacy safeguards, combined with close ties between governments and telcos that are essential to the latter’s operations, mean that operators may end up aiding government-led violations of human rights. Since the Dobbs v. Jackson decision earlier this year reversing abortion rights in the U.S., state governments that have banned abortion can order companies, telcos and platforms alike, to provide information about their users’ geolocation, call records, and messaging data. They can also purchase it from data brokers to aid the prosecution of individuals who seek an abortion. American telco AT&T has so far not yet said how it would handle any such demands. Though AT&T has promised to provide financial support to employees who must travel for an abortion, the company has previously donated to politicians who supported abortion “trigger” laws, designed to outlaw abortions after the reversal of Roe.

Finally, telcos can also facilitate—willingly or not—mass government surveillance. Because they are licensed and operate according to commitments made to government entities, in more authoritarian-leaning regimes, they can become a tool for data collection with little recourse to contradict government demands. This sometimes means taking advantage of “mega events” to accumulate massive amounts of personal data at once. China upgraded its mass surveillance system ahead of the Beijing Winter Olympic Games, while 2022 FIFA World Cup host Qatar is well-known for its violation of privacy rights, including by Qatari-owned telco Ooredoo, which (along with e&) disclosed nothing about how it responds to government demands for user information. In Myanmar, telcos were ordered to install spyware allowing the military to eavesdrop on the communications of its users in the months preceding the country’s 2021 coup. Two telcos that RDR evaluates, Telenor and Ooredoo, were operating in Myanmar at the time.

Companies do far too little to protect their users from this kind of overboard government overreach. Four companies we rank operating in countries with weak democracies or under authoritarian regimes—Airtel, Axiata, e& (previously Etisalat), and Ooredoo—shared little or no data about how they handle government demands for user information and revealed nothing about the volume or nature of such requests. Telcos are even more opaque about how they manage private, as opposed to government, requests for user information. Most of the companies we rank published nothing or almost nothing about such requests. Only América Móvil and Telefónica disclosed clearly that they do not respond to private requests.

Many users are unaware of the full scope of data being collected about them daily by their telecom operator. And yet the lack of transparency from telcos on privacy leaves these users open to considerable risk. In addition to improving their transparency, telco companies should be held accountable for adhering more closely to the principle of data minimization—collecting only the data that is necessary in order to provide specified services to customers. Companies should also refrain from selling data to brokers and conduct due diligence before sharing user information with government entities. Until then, increased public scrutiny, leading to the kind of public reckoning we’ve seen digital platforms face in recent years, would be an important step in ensuring telcos do more to safeguard our privacy.

Tech companies wield unprecedented power in the digital age. Ranking Digital Rights helps hold them accountable for their obligations to protect and respect their users’ rights.

As a nonprofit initiative that receives no corporate funding, we need your support. Help us guarantee future editions of the RDR Telco Giants Scorecard by making a donation. Do your part to help keep tech power in check!