Edzell Castle, Angus, Scotland. Photo by John Oldenbuck via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0

By Veszna Wessenauer and Ellery Roberts Biddle

When Apple announced its plans to tighten restrictions on third-party tracking by app developers, privacy advocates—including us—were intrigued. The company seemed to be charting a new course for digital advertising that would give users much more power to decide whether or not advertisers could track and target them across the web. But we also wondered: What was in it for Apple?

Now we know. The company’s advertising business has more than tripled its market share since it rolled out the App Tracking Transparency (ATT) program in April 2021, which requires app developers to get user consent before tracking them across the web.

Apple has become so powerful that it has changed the rules of the game to its own benefit, and it is now effectively winning. The Financial Times reported in October that Apple’s ads now drive 58 percent of all downloads in the App Store, and more recently reported that ad revenues for major third-party app companies like Facebook and SnapChat have dropped by as much as 13 percent as a result.

It is clear that Apple’s move, alongside Google’s forthcoming transition to tracking people in “cohorts” rather than at the individual level, could shake up the uniquely opaque (but almost certainly icky) underworld of the internet that is ad tech. Every second we spend online, advertisers hawking everything from prescription drugs to political candidates compete for our attention. Internet companies use the ever-growing troves of information that they have about us, much of it gathered up with the use of third-party cookies, to sell ad slots to the highest bidder. Today there is a vast ecosystem of companies that carry out this particular function of using our data to enable targeted advertising. But now two of the industry’s biggest companies are shifting away from this model, albeit in different formats.

Although both companies say that they’re making these changes in order to better protect user privacy, the profit motives are clear, present, and enormous. While the changes may whittle away at the troves of data that so many digital companies have on us, they also will help to consolidate our digital dossiers in the hands of a few uniquely powerful platforms, and reduce or even eliminate many of the smaller players in the ecosystem.

If we’re really moving to a paradigm where first-party tracking dominates the sector, we have to ask: How might this shift affect people’s rights and matters of public interest? We know a lot about how these systems will affect people’s privacy, but what about other fundamental rights, like the right to information or non-discrimination?

Third-party tracking is now tied to some of the most insidious and harmful targeting practices around. With the help of a massive amount of third-party data—collected from third-party websites or apps through technical means such as cookies, plug-ins, or widgets—advertising can be hyper-personalized and tailored to consumer segments or even individuals. Political campaigns can target us to the point that they can swing an election, or tell us to go vote on the wrong day. Conspiracy theorists can capture vulnerable eyeballs and convince people that COVID-19 is a hoax. But it’s not entirely clear that the move away from third-party tracking will change these dynamics.

We can only know how good or bad these moves really are for users’ rights, and for society at large, if we know what’s happening to our data, and if companies give us some ability to decide who gets it and how they can use it. Unfortunately, neither Apple nor Google (nor any of the companies we evaluate) have ever met our standards for these kinds of disclosures.

This season, we’ve been studying this impending shift, assessing the motivations that seem to be driving Apple and Google to make these changes, and comparing companies’ public statements about their plans to their actual policies on things like algorithms and ad targeting. We are using our own standards to inform our understanding of how these changes will affect users’ rights, and what human rights-centric questions we should be asking Google as it rolls out its new “FLoC” system.

Apple is getting creepy

In 2020, Apple’s announcement of the ATT plan triggered loud public criticism from Facebook (now Meta). Most users access Meta’s services via mobile devices, many of which are owned and operated by Apple. This makes Apple the gatekeeper for any application available to iPhone or iPad users, Meta included.

A very public tête-à-tête soon ensued, much of which stemmed from an open letter that we at RDR wrote to Apple, pressing the company to roll out these changes on schedule in the name of increasing user control and privacy.

In response to our letter, Apple Global Privacy Lead Jane Horvath wrote that “tracking can be invasive and even creepy.” She singled out Meta, saying that the company had “made clear that their intent is to collect as much data as possible across both first- and third-party products to develop and monetize detailed profiles of their users.”

We stand by our original position, which was rooted in our commitment to user privacy and control. But we don’t want to see these things come at the expense of competition.

With the new system in place and its newly dominant position in the ad market, we have to ask: What if Apple engages in similarly “creepy” practices by exploiting the boatloads of first-party data it has on its users? It is worth noting that while Apple now requires developers to explicitly capture user consent for tracking (via “opting in”), Apple users are subject to a separate set of rules about how Apple collects and uses their data. If they want to use Apple’s products, they have no choice but to agree. Also, recent research by the Washington Post and Lockdown suggests that some iPhone apps are still tracking people via fingerprinting on iOS, even when they’ve opted out.

The public face-off between the companies helped to clarify what actual motivations may have driven the change on Apple’s part. The changes put the company in an even more powerful position to capture, make inferences about, and monetize our data. If its ad revenues since the change was implemented are any indication, the plan is working.

Apple has published policies acknowledging that it engages in targeted advertising. But there’s a lot missing from the company’s public policies and disclosures about how it treats our data.

- Apple has published no public documentation explaining whether or how it conducts user data inference, a key ingredient in monetization of user data.

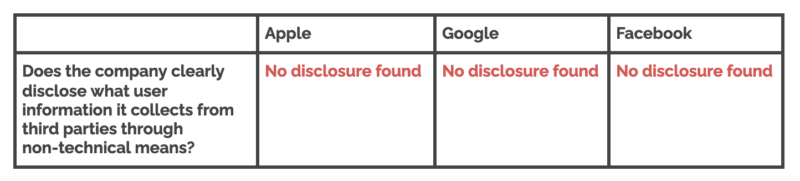

- Apple discloses nothing about whether or not it collects user data from third parties via non-technical means.

- Apple offers no evidence that it conducts human rights impact assessments on any of these activities.

When it comes to FLoC, what should we be asking Google?

Although it won’t debut until 2023, we have some details about Google’s “Federated Learning of Cohorts” aka FLoC, a project of Google’s so-called Privacy Sandbox initiative. The company describes the system as “a new approach to interest-based advertising that both improves privacy and gives publishers a tool they need for viable advertising business models.” What the company doesn’t say is that this new paradigm may actually shut out other advertising approaches altogether.

From what Google has said so far, we know that FLoC will use algorithms to put users into groups that share preferences. The system will track those groups, rather than allowing each of us to be individually tracked across the web. Advertisers will be able to show ads to Chrome users based on these cohorts, which will contain a few thousand people each. The cohorts will be updated weekly, to make sure that the targeting is still relevant and to reduce the possibility of users becoming identifiable at the individual level.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Bennett Cyphers has noted that this weekly update will make FLoC cohorts “less useful as long-term identifiers, but it also [will make] them more potent measures of how users behave over time.” It is also worth noting that the system will also make it much easier to effectively use browser fingerprinting techniques that do enable individual-level targeting.

Learn more about FLoC with these explainers from EFF and RestorePrivacy.

It is important to understand that Google is not actually moving away from a targeted advertising business model. All we really know at this stage is that FLoC will constitute a move towards a paradigm where fingerprinting technology becomes much more powerful and possible to deploy, and where signature tracking techniques are algorithmically driven. If it’s anything like Google Search, or the company’s other products, we can expect to find very little public information on how these algorithms are built or deployed.

We also expect that it will become even more difficult to audit and hold the company accountable than was the case with cookies, which are easy to test for privacy violations. Google has made big promises about supporting and building a more open web. But from where we’re standing, FLoC looks like a new variation on the walled garden.

In fact, documents that were recently unsealed in a massive antitrust suit filed against Google charge that this is all an effort to shore up power in the online advertising market. The suit cites internal company documents saying that Project NERA, the precursor to the Privacy Sandbox, was meant to “successfully mimic a walled garden across the open web [so] we can protect our margins.” The unsealed documents also suggest that the “Privacy Sandbox” name and branding were rolled out in order to reframe the changes using privacy language, and to deflect public scrutiny. The court filings also provide a lot of support for the idea that Google’s main constituency here is advertisers, not users.

Will this really work? Does Google have enough data about us for this to be effective? In short, yes. Google can afford to shift to a system like FLoC precisely because of its monopoly status in the browser market alongside other key markets. Thanks to its preponderance of services—Chrome Browser, Gmail, Google Drive, Google Maps, and, of course, Android—the company has access to incredibly rich and sensitive user data at scale, second to no other company outside China. While Google’s business model relies heavily on advertising, it does not need to rely on third-party data in order to be an effective seller of ad space. With this transition, it could effectively cut out the third-party ad sellers altogether.

It’s also important to consider how this change will affect the broader market. We’re moving from a diverse (if unsavory) array of players in the ad tech underworld, to a paradigm that will concentrate profit and power in the hands of a powerful few. Google controls over two-thirds of the global web browser market. Once the Chrome browser starts blocking third-party cookies, most internet users will be using browsers without third-party cookies.

Although it will probably bring some benefits for users, the change is clearly bad news for many of the actors in the ad tech ecosystem that heavily rely on third-party data and for ad tech firms selling and buying this data. For firms that are not able to collect data on users (in the ways that Google, Apple, or Facebook can) the end of third-party cookies will either snuff out or force radical changes for their business models.

Here are our key questions for Google:

Will users be able to see what groups they belong to and on what grounds under FLoC? Google should make it clear to users what controls they have over their information and preferences under FLoC.

How will Google identify and address human rights risks in its development and implementation of FLoC? Beyond privacy, targeted advertising can pose risks to other rights, like rights of access to information or non-discrimination. If the company identifies problems in these areas, how will it address them?

Will Google stop collecting third-party data on its users through non-technical means when it starts blocking third-party cookies through its browser? Companies may acquire user information from third parties as part of a non-technical, contractual agreement as well. For example, Bloomberg reported in 2018 that Google buys credit card information from Mastercard in order to track which users buy a product that was marketed to them through targeted advertising. Such contractually acquired data can become an integral part of the digital dossier that a company holds on its users and it can form the basis for inferred user information.

Most companies say nothing about whether and how they acquire data through contractual agreements, we found in the 2020 RDR Index.

Data from Indicator P9 in the 2020 RDR Index.

As these companies consolidate power over our data, what should digital rights advocates focus on?

The fact that Google and Apple—both of which have made public commitments to human rights—are trying to position themselves as champions of privacy due to the changes they introduced or are planning to introduce raises questions about whether these companies consider other risks associated with targeted advertising beyond privacy.

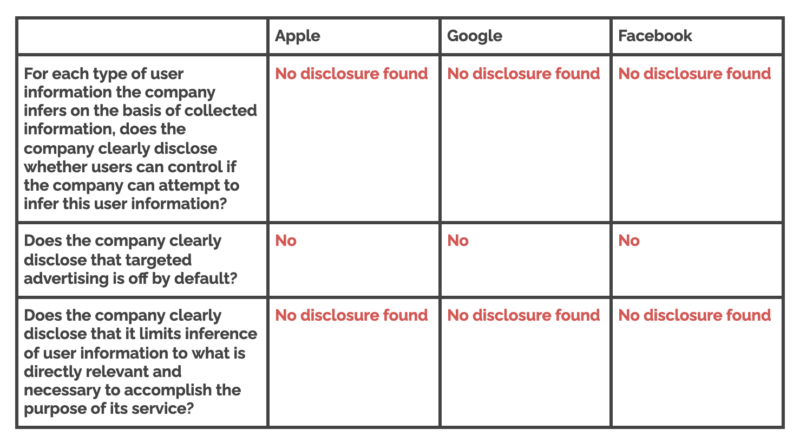

In the 2020 RDR Index we introduced standards on targeted advertising and algorithmic systems to address harms stemming from companies’ business models. None of the digital platforms we ranked in 2020 assess privacy or freedom of expression risks associated with their targeted advertising policies and practices. Facebook was the only company that provided some information on how it assesses discrimination risks associated with its targeted advertising practices, and this was limited in scope.

When we think of some of the long-term societal effects of targeted advertising, like disinformation around elections and matters of public health, these questions must be part of the equation. People need and deserve to have accurate information about how to protect their health in a pandemic. But we know from independent research and reporting that targeted ads have had an adverse impact on people’s ability to access such information. When it comes to elections, jobs, housing, and other fundamental parts of people’s lives, we also know that Big Tech companies have enabled advertising that discriminates on the basis of race, gender, and other protected characteristics. This is equally harmful. In some cases, it is a violation of U.S. law.

Will the move away from third-party cookies mean the end of tracking and targeting? Not likely. User data is still seen as an essential way to generate added value for digital platforms. Companies like Google and Facebook are digital gatekeepers and have their own walled gardens of (first-party) user data that no one else can see. Google claims that with the introduction of FLoC it will not be possible to target individuals anymore, but it is unclear whether and how it will process and infer users’ browser data to allocate them into cohorts.

None of the companies in the 2020 RDR Index provided clear information on their data inference policies and practices.

Data from Indicators P7 and P3b in the 2020 RDR Index.

Are any of these changes going to alter company business models to better align with the public interest? In the case of Google, Chrome users will no longer have to contend with the opacity of third-party tracking. Rather than wondering what third parties might have their data, and how they’re using it, they will know that most of their data sits with Google.

But without more transparency from the company, it will be just as impossible to find out how Google uses our data, and how our data might serve advertisers seeking to do things like swing an election or promote anti-vaccine propaganda. The same will be true for Apple. Until both companies are forced to put this information out for public view, we will have about as little knowledge of (or control over) how our information is being used as we do now.