What you’ll find

Checklist for this stage

There is no one-size-fits-all approach for determining the content, scope, and format of a given project. Available budget, staff, time frames, and other non-financial resources will all factor into your plan. But there are key concepts that are worth clearly defining from the outset.

Writing a project brief will help you establish your vision and decide on the scope of your project.

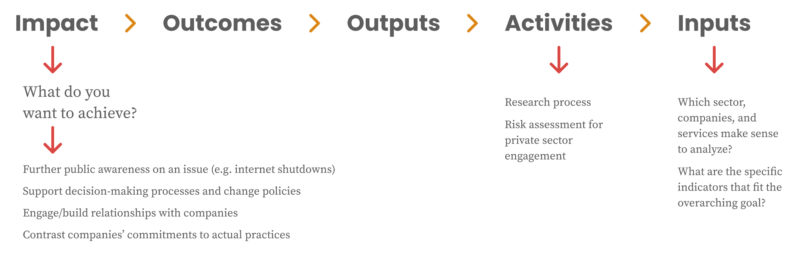

You know that RDR’s methodology will make it easier to identify the how and what of the research study, but before getting to that, the first step of planning should involve defining the why. A straightforward framework for carrying out this process is the “Theory of Change,” which consists of identifying your desired impact, and then mapping out all the steps and conditions that need to happen to accomplish your goal.

After defining the impact, you’ll need to work backwards to identify the outcomes that will allow you to accomplish it, the activities and outputs (the steps of the research itself: producing a report, developing an advocacy strategy, company engagement, etc.) that will help you realize this outcome, and, finally, the inputs that you need to in order to implement each activity.

Some questions that can help guide this process:

Defining the problem: Tech companies pose many threats to people’s rights.

Stakeholder mapping:

Once you’ve completed the Theory of Change process, it’s time to focus on the project brief itself. There are no strict rules for writing the brief, but the document should serve as a framework for the project. With all the details laid out from the outset, we can make sure everyone working on it is on the same page.

To that end, here are the basic elements that should be included in every brief:

A risk assessment is the process of identifying potential threats that can jeopardize the preparation, implementation, and outcomes or results of a specific activity, or an entire project. Carrying out this analysis during the planning stages allows you to anticipate and mitigate those risks when they occur. By staying one step ahead, you can adapt when situations arise that compromise your research or advocacy goals, and ultimately come up with alternative solutions.

There are three main categories of possible risks for such a project, but feel free to add any others that makes sense within your specific context:

There are three main categories where most risks for a project may fall into, but feel free to add any other that makes sense for your specific context:

project objectives

project outcomes / outputs

security of personnel

For example, if you’re working with local researchers, they may lack capacity to complete research tasks, or some conflicts of interest.

For example, companies may be unresponsive or dismissive of the research process or the findings/results, and in worse cases, companies may respond with hostility to engagement (with legal threats). The data collected through the research may be compromised, due to technical reasons (damaged hardware, computers infected with ransomware, etc.), or even political motivations (equipment seized by authorities, stolen, etc.)

For example, political threats or pressure due to receiving foreign funding. Repressive regimes (or companies colluding with such regimes) may view the project/research as a threat, and target them for harassment or arrest.

To begin this process, start by describing the specific risks identified in each category. Next, evaluate the likelihood of each risk occurring and describe the potential impacts. Finally, you should have a mitigation plan in place to address these potential impacts, describing the specific actions you’ll take if any of these risks become reality.

For the purposes of this guide, we’ve created the following template that you can use to document the risk assessment process. We have included some examples in each section, to give you an idea about how we use it ourselves. This may or may not reflect your own context. We encourage you to adapt it so that it suits your specific needs and local context.

At this stage, you already have a clear idea of the scope of your project. That means it’s time to define the substance of the research itself: Which indicators from RDR’s methodology are going to be evaluated and for what companies?

In order to choose the right indicators, there are at least three key factors to take into account:

Although it may be tempting to try and cover as many indicators as possible, they can quickly add up and result in greater research time than what was originally envisioned. There is power in simplicity. Try to focus only on the most important issues. Being clear and simple will also help make the eventual research findings more accessible to your specific target audiences.

Based on the type of company being evaluated, adaptations have focused on specific indicator subsets. This was the case for a study of messaging apps in Iran. Others have focused exclusively on one category of indicators, like the study of internet service providers in the city of New York, which focused on online privacy.

According to the policy objectives outlined in your Theory of Change and project brief, you can then customize the selection of indicators, and their specific elements, to suit your goals.

The RDR Corporate Accountability Index focuses on consumer-facing companies, but any technology-related business can be evaluated using the methodology. Beginning with the 2020 RDR Index, we have classified companies into two categories: telecommunications services and digital platforms.

Telecommunications companies can be a strong target for a first round of RDR-inspired research, given that there is usually more than one company in the country that offers these services, allowing for comparisons and the leveraging of the competition angle for advocacy. Moreover, there’s a good chance that at least one subsidiary of a parent company already ranked in the RDR Index will be among the companies evaluated, which introduces further opportunities for comparison and engagement to achieve change.

With digital platforms, there are numerous angles through which exploration using our methodology might be possible. Social media networks, messaging services, e-commerce and shopping platforms, financial technologies, online storage, Internet of Things appliances and gadgets, health tracking, grocery delivery or other “gig economy” services are just some of the industries that are growing in multiple regions around the world.

The key point to bear in mind is making the connection between the policy issues that fuel the research and the kind of companies that play a role in shaping it, either directly or indirectly. When deciding between companies, another aspect to take into consideration is the user base or market share, to determine if you want to focus on the main players in the ecosystem that concentrate greater power.

The human rights against which we rank company disclosures are universal, so we rank company disclosures the same way regardless of the legal requirements that companies face in different countries. However, as part of our Index research, RDR conducts a jurisdictional analysis that examines what factors may limit or prevent companies from performing well on certain indicators in a given jurisdiction and this information is incorporated into our final report.

We encourage companies to advocate for policy and legislative approaches that maximize their ability to respect freedom of expression and privacy. This is why, when adapting the methodology, looking at the jurisdictional environment remains important.

To facilitate this process, we’ve created a jurisdictional analysis survey, which entails a series of questions to help you paint a broader picture of the laws and regulations that are connected to the specific indicators you’ll be researching.

Once the list of indicators, with each of their elements, and the companies is finalized, it is time to determine how you will carry out the research itself.

For the RDR Index, the research process involves the following steps:

Step 1

Primary Data Collection. Primary researchers are responsible for verifying results of the previous RDR Index. If the company policy has changed, and in the case of new indicators and elements, primary researchers are responsible for collecting data and providing an evaluation of those policies. Step 1 researchers will also conduct an evaluation of how the current policy compares to the previous RDR Index.

Step 2

Secondary Review. Secondary reviewers fact check the assessments provided by primary researchers in Step 1, including agreeing or disagreeing with the year-on-year-analysis.

Step 3

Review and Reconciliation. The RDR team discusses the results from Steps 1 and 2 and resolves any differences that arise.

Step 4

Company Feedback. Companies have the opportunity to review the preliminary evaluation and provide feedback to the RDR team. The team evaluates the input from companies to determine if it warrants a change in the evaluation.

Step 5

Processing company feedback. RDR considers the feedback from companies, and makes any adjustments to evaluations, as needed.

Step 6

Horizontal Review. The RDR team cross-checks the indicators to ensure they have been evaluated consistently across each company.

Step 7

Final Scoring. The RDR team assigns final scores. The final results also include an analysis of the company’s scores from the previous year.

Steps 1 to 3 can be considered the baseline for any project, given that they encompass the substantive activities needed to evaluate the indicators and review the findings. By using the RDR process as a template, you can adapt them according to several factors, including the number of researchers on your team– if you’re doing the project by yourself–the amount of indicators and companies, if company engagement is part of the strategy, as well as any other external circumstances (for example, if the research results are part of a broader advocacy strategy to influence a time-sensitive event such as a bill passing through congress/parliament).

Remember to be mindful of the time availability of staff who will be working on this research, in order to calculate how feasible the inclusion of a given number of indicators and companies would be. As a general rule, the assessment in Step 1, for each indicator you select, should take around 1 hour, but if it’s the first time doing this type of research, it can take longer.

To carry out the data collection, the RDR team uses a system designed and developed in-house, customized to facilitate managing the information for each company and the indicators evaluated, as well as the analysis of the eventual said data. If you’re interested in using our data collection infrastructure for your project, don’t hesitate to message us at partnerships@rankingdigitalrights.org

If you are carrying out the research in a country that has a data protection law, or other kind of regulation that recognizes data rights, consider using data subject access requests to gain further insights about the data practices of the companies you are evaluating. These requests can be useful to provide context for the companies’ privacy policies, particularly for the indicators about:

Moreover, if any of the companies have engaged in negotiations or contracts with government bodies, perhaps that’s also an opportunity to leverage freedom of information requests (again, depending on the legal frameworks and channels available to you) to learn about specific information that the company may have shared with government officials. Even if it’s not directly related to indicators, it may serve your project’s goals and provide a broader picture about how the company operates.

Freedom of information requests may also be useful to complement the data from your analysis. If you’re studying indicators about government demands (including judicial orders) to remove, filter, or restrict content or accounts (F5a and F6), as well as demands for user data (P10a and P11a), you may consider asking law enforcement agencies, or the ministry of security in charge, whether they have requested this type of information from the companies being studied.

You will need to be mindful not only of the legal frameworks and procedures available to you, but also of your risk assessment planning.

Depending on the scope and time available for the project, you may be interested in complementing the analysis of the companies’ policies with some technical data that can strengthen your arguments and provide additional evidence for your findings.

Fortunately, there are several tools at your disposal, with varying degrees of technical expertise required to run them. We’ll explore some examples below.

If your project involves studying telecommunications companies and focusing on our network shutdown indicator (F10)–which looks at the circumstances under which a company may shut down or restrict access to the network or to specific protocols, services, or applications on the network–you may be interested in learning about the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI).

Their tool OONI Probe allows you to test the blocking of websites and apps, as well as measure the speed and performance of your network. Besides websites, the app tests the availability of the most popular instant messaging services, namely WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Signal, and Telegram, and also checks if Tor and VPNs are blocked.

It’s important to note that you need direct access to the specific network you’re testing–you need to be using the services of the mobile carrier or internet service provider–so it may be challenging to study multiple companies and services at once. With that said, OONI Probe’s mobile app can be used from both Android and iOS devices, as well as Windows and macOS, so it may be possible to crowdsource tests from a network of allies in your country or region. Alternatively, you can use the OONI Measurement Aggregation Toolkit (MAT), which will allow you to create your own custom charts based on aggregate views of real-time OONI data collected from around the world.

If your project involves studying apps or websites that offer services such as e-commerce, fintech and banking, food delivery, messaging, cloud storage, entertainment streaming, online learning, among others, there are several privacy indicators that can be complemented with technical data.

For indicators related to the collection, sharing, and purposes of user data (P3, P4 and P5), you can use the following tools to run tests and compare the results with the company’s disclosures in its privacy policy, in order to provide further context and analysis:

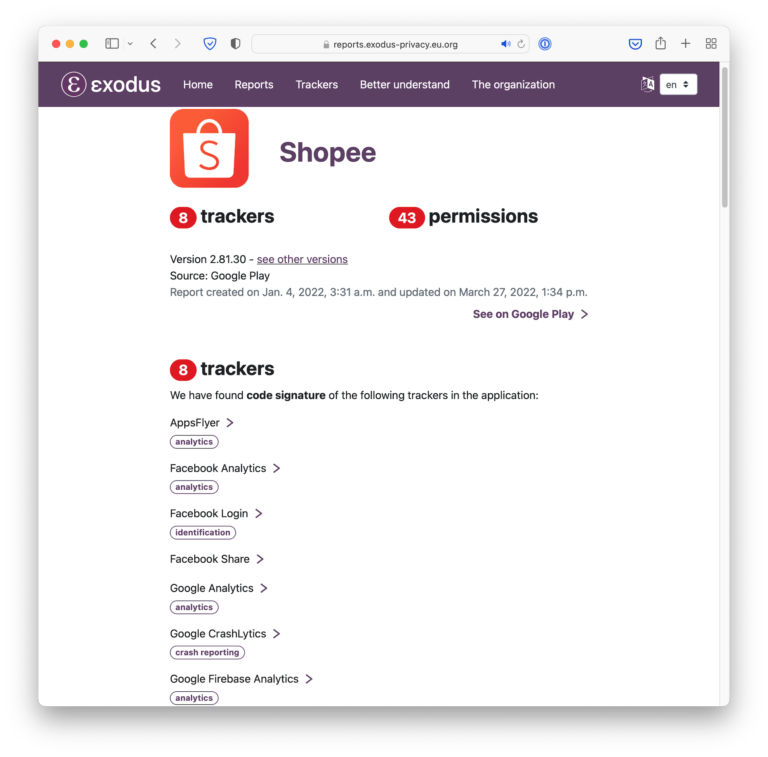

Exodus Privacy, a French non-profit organization, provides a tool to analyze Android applications, producing a report that mentions what trackers are embedded into the app, as well as the list of permissions it requests to operate on the smartphone. You can test apps directly from their website here.

The Markup, a non-profit newsroom, developed Blacklight, a real-time website privacy inspector that scans and reveals specific user-tracking technologies on any website. Blacklight tests for ad trackers, third-party cookies, tracking that evades cookie blockers, session-monitoring scripts, keystroke capturing, and if the website sends information to Facebook and Google. The results also include a brief description of each ad-tech company that the website interacted with.

Privacy International, a global non-profit NGO, developed the Data Interception Environment, a comprehensive and advanced tool that allows you to acquire technical understanding of how an app is capturing, processing and transferring data to third parties. The only caveat is that some technical skills are required to set up and run the tool, but PI has detailed tutorials to help you in the process.

If you’re studying whether companies disclose that user communications and private data are encrypted (indicator P16), there are some services that can test if a website has configured their security according to industry best practices. Tools like SSL Server Test and Security Headers can be used to run tests for any website and get a detailed report with their performance.