Executive Summary

Executive Summary

The 2025 RDR Index: Big Tech Edition is the seventh iteration of our rankings, in which we evaluate 14 of the world’s largest digital platforms, encompassing 43 individual services, on their policies and practices related to corporate governance, freedom of expression, and privacy. The 2025 RDR Index is the first full evaluation of these companies since 2022 and marks a decade since the first edition of the RDR Index was published in 2015.

In 2022, RDR warned that tech giants were pursuing “business as usual” even in the face of growing political instability and rising authoritarianism. We demanded that, among other things, tech giants take more concerted action in conducting human rights impact assessments to assess their algorithmic systems. We also asked that they improve transparency of the mechanisms that enable the surveillance advertising business model, which fuels the profit of companies like Alphabet, Meta, and X.

This call rings even truer in 2025, as global politics have shifted to the far right—from the U.S. and Europe to South Asia and South America—challenging fundamental human rights. At the same time, the growth of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) has exploded since the release of ChatGPT in 2022, compounding risks to democratic processes and supercharging concerns over AI’s environmental impacts.

Meanwhile, war and violence continue to unfold globally, including in Ukraine, Palestine, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan. Technologies developed by some of the companies assessed in the RDR Index are deeply intertwined with these conflicts. Alphabet, Amazon, and Microsoft have all developed tools meant for war and integration with lethal weapons. Their cloud infrastructure has powered military campaigns. Meta’s social media platforms are still major conduits of propaganda, while X’s role in disinformation and the poor enforcement of content moderation in the context of war is under investigation for contravening the European Union's Digital Services Act.

As companies race towards developing AI, concentration of power within Big Tech has never been more flagrant. Research by SOMO, a corporate accountability non-profit, has shown that Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, and Microsoft acquired an average of one company every eleven days between 2019 and 2025. Three companies (Alphabet, Meta, and Amazon) soak up two-thirds of all advertising revenue on the internet by controlling the infrastructure ads flow through and wielding immeasurable volumes of personal data.

This market concentration means greater reliance on the services of a few big platforms, giving them almost unilateral power to dictate who can access these and when. The power is in turn reinforced by organisational structures that limit accountability, giving executives and insiders veto power over petitions for change from their shareholders.

The legal system is cautiously responding to these systemic issues. In August 2024, a judge from the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that Google had an illegal monopoly over internet search. In April 2025, another judge ruled that Google illegally built a monopoly over the publisher tools and the software system of the advertising network that has enabled its colossal growth.

The widely shared photo of U.S. Big Tech CEOs in the front row seats of the U.S. presidential inauguration on January 20, 2025, encapsulates the power and political capital these companies have amassed. Extensive connections and crossflows between Big Tech and government bodies allow them to further avoid much-needed scrutiny, as human rights and democratic structures face unprecedented attacks in multiple flashpoints around the world.

The 2025 RDR Index: Big Tech Edition

2023 was a pivotal year for RDR, as we celebrated ten years of holding tech power to account. In January 2024, RDR began a new chapter in its corporate accountability journey with a transition to the World Benchmarking Alliance. The 2025 RDR Index: Big Tech Edition marks the first publication of our flagship benchmark as part of this new institutional home.

In this 2025 edition, we evaluated 43 digital services that people rely on in their daily lives, from AI assistants like Alexa and Siri, to messaging apps like WhatsApp and WeChat, to user-facing cloud and email services. The companies assessed control online information flows and the web's underlying infrastructure, which is used by more than 5.5 billion people worldwide.

What's new in this edition:

- We officially added ByteDance to our list of assessed companies, carrying out a full assessment of its TikTok platform. In 2021, we carried out exploratory research comparing the performance of TikTok and Douyin on a subset of indicators. Beginning with this edition, we are assessing the company against its global peers.

- We removed Yahoo Inc. from our list of assessed companies, despite its comparatively favorable performance in previous editions, due to its structural misalignment with the World Benchmarking Alliance’s selection criteria under the company’s current private-equity ownership.

This is also the last assessment of the videoconferencing service Skype, as Microsoft announced plans to shut down the service in May 2025.

In the 2025 edition, we have also improved our Data Explorer, making it easier and friendlier to navigate the results. Further, we continue to publish our thematic Lenses, which look at various groups of indicators organized around key topics, such as algorithmic transparency, data handling, government demands, and targeted advertising, among others.

The Good News

Overall, most companies’ scores have improved since the last RDR Index, although no company scored over 50 percent. This is the third assessment since our 2018 evaluation where digital platforms headquartered outside the U.S. have led year-on-year progress. This year, the three previously assessed Chinese companies—Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent—have improved the most, driven by increased transparency in their governance disclosures.

The three Chinese companies we assess conducted regular human rights impact assessments to identify how government regulations and policies affect freedom of expression and information as well as privacy. In addition, all three disclosed more information about how they manage and oversee the effects of their policies and practices on freedom of expression and privacy. Notably, these transparency improvements are reflected in increased disclosures in their ESG reports.

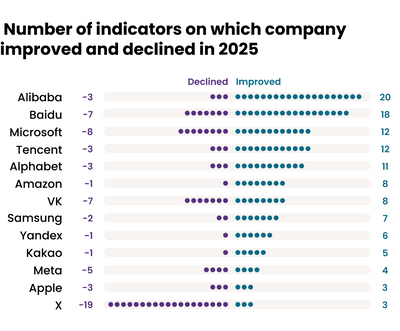

This year, we also looked at the total number of indicators on which each company improved and declined across the three measurement areas covered by our assessment—governance, freedom of expression and information, and privacy. Our findings highlight notable progress by companies including Alibaba, Meta, and Samsung.

- Alibaba showed improvement across the largest number of indicators and the strongest improvement overall, driven particularly by its growth in governance, the measurement area where it made the most progress. However, the company’s starting point was low due to poor performance in past editions and, overall, its governance score still ranks in the bottom half of the assessed companies.

- Meta, like other social media companies, often comes under close scrutiny due to the socio-political impact of its platforms and their algorithms. Our research found that Meta now discloses more details about how it uses algorithms to curate, recommend, and rank content that users can access on Facebook and Instagram. While the purposes for which Meta uses algorithms remain a fundamental concern, the company’s improved disclosures on its practices are noteworthy. Since 2022, Meta has also made some of its algorithmic system use policies easier to find. Meta also enabled end-to-end encryption by default on Messenger and Instagram chats, adding an important layer of security that had already been implemented on WhatsApp in 2016.

- Samsung far outpaced its peers on transparency improvements in the privacy category due to increased disclosures on its data breach policies. The company stated that it will notify users and relevant authorities without delay in the event of a breach and shared more information about its process for notifying users whose data has been compromised. Samsung also broadened its privacy policy to include more information about cookie technologies and the collection of users’ data from third parties. However, similar to Alibaba, Samsung began from a low starting point and still has a long way to go. Only Amazon and VK performed worse than Samsung in the privacy category; the company must maintain its momentum to earn the enduring trust of its users.

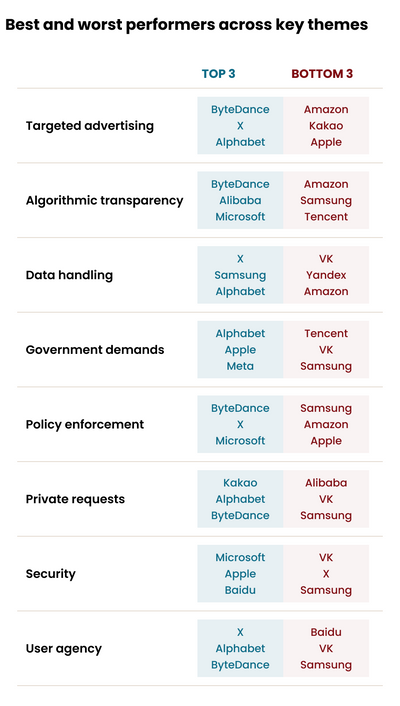

Finally, as a newcomer to the RDR Index, ByteDance ranked sixth overall, while TikTok, a photo and video sharing service, came second after YouTube in the freedom of expression measurement area. Its direct rival, Instagram, came close behind. The photo and video sharing services had the smallest gap between the highest and the lowest scores illustrating how close these services are in terms of their transparency. Furthermore, when compared to the other social media[1] companies, TikTok ranked third on privacy, tied with LinkedIn. Many of TikTok's disclosures are comparable to those of other large U.S. platforms. Furthermore, TikTok was the only platform that clearly indicated it does not allow advertisers to target specific individuals. It also shared clear explanations about how its recommendation algorithm works as well as a detailed approach to governing online advertising content and targeted advertisements.

The Bad News

Significant declines in transparency

A significant takeaway from the 2025 RDR Index is the glaring lack of transparency in Big Tech companies’ handling of private requests for user data or to restrict content and accounts. The U.S. tech giants still disclose more information about how they respond to government requests for content restrictions and user data, maintaining a decade-long trend. In contrast, most companies continue to disclose close to nothing about how they handle private requests for user information or account restrictions. In fact, Samsung discloses no information related to private requests. Notably, the company does not publish a transparency report—where companies usually disclose this information. While Alibaba and Tencent reported disclosures in 2022 on their process for responding to private requests to remove, filter, or restrict content or accounts, in 2025 these disclosures are outdated or now lack critical information following a policy update.

Another concerning takeaway is that some of the largest Big Tech companies are failing to conduct regular human rights impact assessments to identify how their processes for policy enforcement or targeted advertising policies and practices affect users’ rights to freedom of expression, privacy, and non-discrimination. Only Alphabet disclosed that it was assessing the impacts of its targeted advertising policies and practices, though its disclosure was limited and unclear as to whether the assessment was part of a systemic due diligence process. Both Meta and Microsoft are now less open about whether they conduct impact assessments on targeted advertising policies. Meta last published its Civil Rights Audit Report in 2020, rendering some of its pathfinding disclosures on ad targeting impacts outdated. However, the company did publish a blog on its civil rights progress in 2023, which highlights the development of a framework to assess civil rights impacts; although additional information is limited. Microsoft made no further update to its Salient Human Rights Issues Report, which was last published in 2017, and stopped publishing data updates on how it enforces its advertising policies.

Among all the companies evaluated, X (formerly Twitter) stands out as the most notable case of declining transparency. The company’s transformation from the publicly listed Twitter to the privately held X Corp. and the elimination of its human rights team coincided with a significant drop in transparency across its governance, freedom of expression, and privacy practices. X showed a drop in transparency across more indicators than any other company in this year’s assessment and the largest overall decline in the history of the RDR Index.

Notably, X did not publish a transparency report in 2022 or 2023. When it finally did so in September 2024, the report fell outside our policy cut-off date and thus was not considered in our final assessment. The company did issue a short blog post in April 2023 containing a stripped-down overview of how much content it restricted in the first half of 2022 and signaling that it would “review [its] approach to transparency reporting.” Nonetheless, in a further erosion of its disclosures, X has removed many of the transparency reports published since 2011 under its previous ownership.

The gears behind Big Tech's business model remain opaque

In 2020, RDR introduced new standards to better hold companies accountable for their business models, built on algorithms and targeted advertising that expose users to harms such as disinformation and the potential for election interference.

For the third assessment in a row, none of the assessed companies earned more than 50 percent of the possible score in the targeted advertising indicators and elements.[2] Alphabet and Meta’s transparency on the topic even declined slightly in 2025. Almost none of the companies shared whether they had conducted a targeted advertising human rights impact assessment. The one exception was Alphabet, as the civil rights audit commissioned by Google encompassed the content moderation of the company's advertising platforms. However, it was unclear whether this audit was part of a systemic due diligence process.

Companies' transparency on policies governing prohibited advertising content remained largely unchanged, with notable improvements from Alibaba, Tencent, and Yandex. While still far from the 50 percent mark, companies also showed improvement in their policies governing advertising targeting parameters.

Despite these improvements, eleven companies disclosed no information about advertisements removed because of breaches to ad content policies, and no evidence of enforcing their ad targeting policies. The only exceptions were Alibaba, Alphabet, and ByteDance.

Companies are yielding to government demands with limited transparency

2024 brought with it a “super-cycle” of elections, as more than 60 countries, home to billions of people, went to the ballot box. It also served as a stress test for the online information ecosystem and the mechanisms that support free and fair societies. Around the world, some governments resorted to censorship to undermine democratic processes, especially elections, while civic spaces continued to shrink.

Twitter, once praised for pushing back against broad and unjust government orders to block accounts, increased its compliance rate for government demands under Elon Musk's ownership. In 2025, the company demonstrated the sharpest drop in transparency on government demands for user data and for censorship[3] among all the assessed companies. Meanwhile, though Amazon published an Information Request Report in 2024, it shared no information about its process to restrict content or accounts.

While almost all the assessed companies provided some degree of insight into their processes for complying with government orders to hand over private user data, half of them did not publish any type of transparency report showing the number and types of such demands received and complied with.

Our findings reinforce long-standing concerns over companies' opaqueness in dealing with governments. The events of the past three years have magnified these concerns. Since the last RDR Index in 2022, the European Commission has repeatedly voiced its intention to expand law enforcement's access to people's private data, with intentions to weaken or even break encryption for communications. Meanwhile, in 2025, following pressure from the UK government demanding Apple implement a “backdoor” to access user data, Apple decided it would no longer provide users in the UK with access to its Advanced Data Protection tool, to avoid building such a backdoor. Moreover, analyses of companies' transparency reports show that government demands for user data have steadily risen over the course of the past decade.

Companies are failing to tell us how they enforce their own policies

Some tech giants may be relatively explicit about the rules they have in place to manage the torrents of content that flow through their platforms every day. But they do not always show how they put them into practice. Our policy enforcement indicators and elements[4] assess how clear companies are about their content policies and whether they publish information about how they enforce them. Here, too, we found pervasive gaps, even as some tech giants begin to uproot the policies they once upheld.

TikTok outmatched all other services in its transparency on policy enforcement. Conversely, in the past three years, the same companies that previously drove watershed progress in this area have largely stalled and plateaued, despite plenty of room for improvement.

Alphabet (Google) and Meta’s dominant services embody this in distinct ways. The former is hobbled by the gap between YouTube’s relative transparency on the video content it restricts and the scarcity of analogous information for other services. The latter still aggregates much of its reporting into a broad “content actioned” category, rendering it impossible to distinguish between how often it takes down posts, bans accounts, and applies fact-checking labels. Similar examples abound.

Tech giants’ opacity in this area is especially hazardous given the directions in which their policies are evolving. In January 2025, Meta announced the dismantling of its third-party fact-checking program, beginning with the U.S, and updated its policies to allow dehumanizing language. YouTube’s removal of “gender identity” from its hate speech policy in the same period also prompted widespread outcries.

These examples highlight a growing trend across Big Tech companies: They are revisiting and revising their policies to justify their existing behavior. A troubling pattern is emerging, prompting us to strengthen our call for companies to enforce their policies.

Conclusion

Despite the myriad new risks presented by today’s tech landscape, including the ongoing AI boom, Big Tech platforms are still conducting business as usual. Notwithstanding the occasional notable improvement, they are stalling in areas where progress is most urgently needed. They are also signaling a willingness to abandon the principles, protections, and communities they previously embraced to align with changing political winds, including those that have driven the recent far-right resurgence. The stagnation in U.S. companies’ overall performance in the benchmark is a symptom of these shifts.

The tech ecosystem needs to be jolted out of its inertia. The current landscape calls for renewed strategies. Civil society, investors, and policymakers must apply pressure on the world’s largest companies to stop backtracking on existing commitments and to respect fundamental rights. Tech giants must demonstrate that, after a decade of progress on corporate accountability for digital rights, they are committed to tangible action and transparency.

Read more in the company scorecards and key findings for the 2025 RDR Index: Big Tech Edition.

Footnotes

[1]Social media companies assessed by Ranking Digital Rights include Social Network and Blogs services: Facebook, LinkedIn, X.com, Baidu PostBar, Vkontakte, QZone and Odnoklassniki; as well as Video and Photo Sharing services: YouTube, TikTok and Instagram

[2]Learn more about our targeted advertising lens here.