Key Findings

Three years on, U.S. tech giants are moving slow and not fixing things

Three years on, U.S. tech giants are moving slow and not fixing things

By Jan Rydzak

Kings of the Hill

On April 17, 2025, a U.S. district court ruled that Alphabet (Google) held and deliberately furthered a monopoly in the ad tech industry. The landmark decision was the second antitrust loss for the tech giant in less than a year, arriving in the wake of another resounding ruling on its dominance of online search. Three days earlier, Meta’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg took the stand in an antitrust trial against Meta that could lead to the breakup of its social media empire.

All five of the world’s largest companies today are U.S. tech giants. Apple, which in 2018 became the first company in history to be valued at more than USD 1 trillion, has since been joined in the “ trillion-dollar club” by five of its industry peers: Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Meta (formerly Facebook), Microsoft, and Nvidia. The last time Big Tech did not hold a majority among the world’s five largest megacap mammoths was in 2010.

The platforms these companies operate were already supersized when RDR first put them under the microscope in the 2015 RDR Index. But ten years on, the landscape and its power structures have undergone a radical transformation.

What precisely has changed? The most salient feature of the past decade is the consolidation of power by the largest players in the industry. The 2010s were marked by a stint of of acquisitions that brought a string of platforms under the banner of Big Tech, including Instagram, LinkedIn, Skype, Vine, and WhatsApp.[1] Today, the GAFAM[2]giants are worth between five and six times their market value in 2015, though they dwarfed most of their peers even then. Big Tech has simply never been this big.

Ten years ago, the impact of these consolidations on power, competition, and diversity in the tech ecosystem were unclear. People around the world remained broadly enthusiastic about digital platforms. A steady stream of positive press coverage had further buoyed social media giants like Facebook and Twitter ever since media outlets positioned them as “liberation technologies” during the Arab Spring in 2011-12.

In 2025, that optimism is widely considered a distant memory. In Thales Group’s 2025 Digital Trust Index, global trust in social media companies dipped to a record low of 4%. Many of the survey’s 14,000 respondents cited the proliferation of false and misleading content and the platforms’ insatiable appetite for personal data as their key grievances.

In an industry where the doctrine of “move fast and break things” reigns supreme, the largest players have had extraordinary staying power. Meta alone touts nearly 3.5 billion daily active users across all its services. Google Search still commands between 80 and 90 percent of global search traffic, just like it did in 2015. Among the 14 U.S. platform services RDR first assessed in 2015, only one (Vine) no longer exists; another (Skype) is scheduled to shut down in the days following the launch of this report, 22 years after its debut.

But some aspects of the tech titans’ structures and operations seem nearly impervious to change. As RDR has highlighted in the past, the CEOs and founders of Meta and Google continue to exercise absolute decision-making power through supervoting shares that allow them to overrule any dissent from their chosen directions by their companies’ investors. While the overwhelming majority of independent shareholders vote every year to change this status quo, their efforts are undone each time by the same veto power they seek to break.

On the surface, the ad-targeting business model that allowed founders and executives to expand their empires to unprecedented levels also appears unassailable. Google, Meta, and Amazon dominate this ecosystem: Meta still derives nearly all of its revenue from targeted advertising, while Google’s ad revenue accounts for 86% of its total. The three U.S. giants and their smaller peers are surrounded by a dense and largely unregulated web of data brokers who keep the system running on people’s most intimate data. The industry’s mass pivot to generative AI has only been a force multiplier for this trend, as most of the large language models (LLMs) underpinning it run on unfathomable volumes of personal information obtained through mass data scraping.

Status Update: Our Findings

The last time RDR evaluated the world’s dominant platforms was in the 2022 Big Tech Scorecard, exactly three years ago. The industry was in the grip of mass layoffs. OpenAI was eight months away from launching ChatGPT, the generative AI chatbot that would trigger a race to integrate “AI-powered” functionalities into every digital service. Elon Musk had just made an offer to purchase Twitter, which had topped RDR’s ranking of digital platforms for two consecutive years. The ensuing legal battle over Twitter’s ownership ended with Musk’s takeover of the platform later that year and its subsequent rebranding to X.

The U.S. tech giants had three years to make progress. But our results strongly suggest they don’t have much to show for it.

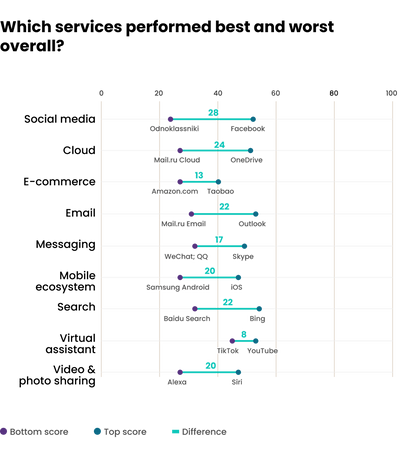

In absolute terms, the American incumbents maintained their lead over their Chinese, Korean, and Russian counterparts—a pattern that dates back to the first RDR Index. Microsoft topped the 2025 edition with a score of 50% and an even spread of disclosures across its five assessed services (Bing, LinkedIn, OneDrive, Outlook, and Skype). Google (47%) and Meta (46%) also made the podium; Apple (44%) shared fourth place with South Korea’s Kakao (44%).

Silicon Valley’s tech titans once again outperformed their rivals on transparency about critical governance processes, from whistleblower protections to human rights due diligence. Their disclosed privacy and security protections were also among the strongest, with Apple setting the tone. For all but one of the nine platform types RDR assesses, the top performer was a U.S. service; the lone exception was e-commerce, where Alibaba’s Taobao marketplace once again handily outmatched Amazon’s domestic platform across the board.

But when parsed with a finer-toothed comb, the data tells a deeper story. Some of Silicon Valley’s tech titans ranked higher this year not due to any major policy improvements of their own, but rather Twitter (X)’s precipitous drop in transparency, coupled with the removal of Yahoo from the RDR Index. X’s decline was driven largely by a near-total collapse of its key governance disclosures and the discontinuation of its transparency reporting for more than two years (see our key finding, Private Platforms Are Falling Short on Transparent Governance).[3] On the other hand, X’s closest competitors in the U.S. largely maintained their pre-existing disclosures.

Freedom of Expression and Information

Reporting on government demands provides a useful window into these dynamics. Google, whose pioneering 2010 transparency report was the first of its kind published by a major tech company, continued to lead the way with its comprehensive transparency reporting portal. Its few shortcomings included a lack of insight into the prevalence of informal pressure to remove content.

Yet, in the three years between 2021 and our policy cutoff date in August 2024, neither Google nor any of its American peers had made the slightest improvement in this area. X, whose new owner had touted transparency as “ the key to trust,” explicitly capitulated on transparency reporting in 2023, permanently preventing any insight into the pressure it received from governments to remove content and share user data in this period. Amazon remained silent on government-requested content removals worldwide, despite a shareholder push to break the silence and a 2024 investigation by Citizen Lab revealing extensive censorship blocklists. Conversely, a successful shareholder campaign convinced Apple to release a breakthrough (if incomplete) App Store Transparency Report, revealing an extreme skew in the volume of apps removed at the behest of the Chinese government.

The U.S. platforms’ lack of progress and some companies’ pivot away from it means the overall momentum on government demands is going in the wrong direction at a very precarious time. Looming risks to privacy and human rights are reinforced by the widespread weakening of protections for vulnerable groups. Unprecedented events like Apple’s removal of its strongest end-to-end encryption in the UK under government pressure accentuate the urgency.

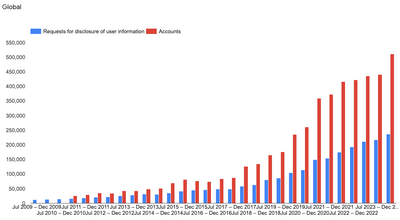

Google’s own data reveals an unmistakable upward trend in the amount of content governments request to remove and the number of attempts to procure people’s data. In the first half of 2024, Meta restricted nearly 750 times more content in response to government pressure than it had in the same six-month stretch the year before. While the surge was overwhelmingly driven by new legal requirements in a single country (Indonesia), the number of restrictions in 2024 across all other jurisdictions was still double that of the previous year.

What about the U.S. giants’ own enforcement actions? Ten years ago, not a single company assessed in the first RDR Index published data breaking down the content and accounts they restricted for purported policy violations. That same year, Etsy became the first tech company to publish a transparency report containing at least some of that information. YouTube and Facebook both began disclosing their own content restriction statistics in 2018.

Since then, tech platforms’ content governance practices have consistently dominated news cycles. Growing advocacy and regulatory pressure on tech companies have provoked sweeping shifts in the landscape of transparency reporting. Ten of the platform services covered in the 2025 RDR Index are now classified as Very Large Online Platforms or Search Engines under the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA).[4] Nine of them originate in the U.S. The DSA’s many provisions largely overlap with the RDR Index indicators, compelling clearer processes and more detailed disclosure of content restrictions in the EU.

But based on our results, the progress unlocked in Europe has so far failed to carry over to Big Tech’s global disclosures. In the 2025 RDR Index, newcomer TikTok surged ahead of all the pioneers of transparency reporting in our policy enforcement focus area. TikTok took the lead that Twitter (now X) previously held, even significantly improving on the latter’s peak performance. China’s Alibaba and Tencent and Russia’s VK made the greatest strides in transparency on content governance, even though none of their assessed services are bound by the DSA’s most stringent transparency requirements. Alibaba’s Taobao marketplace now rivals Facebook on this front, with both landing in the top five out of all 43 platform services.

Meanwhile, the American tech giants who pioneered transparency reporting have barely made headway since 2022. Even the leading reports remain hampered by omissions, ambiguities, and aggregation.

Some platforms still blur the lines between types of moderation, combining everything from account bans to fact-checking labels into broad categories ( Facebook, Instagram) or limiting themselves to removals ( YouTube). Others do not provide a full picture of which rules were violated ( LinkedIn, Amazon). Most do not break down the types of content restricted. Content moderation appeals processes—key conduits of grievance and remedy—remain exceptionally opaque, with only Meta’s rising above the rest. This echoes academic findings showing no Big Tech platform coming anywhere near full alignment with the revamped Santa Clara Principles. Co-created by RDR, the Principles are one of the most widely embraced proxies for what good disclosure on content governance looks like.

Erosion of past progress marred the landscape further: Meta’s WhatsApp stopped sharing new information on its efforts to combat automated spam, which at one point entailed banning 2 million accounts over the span of two months. Microsoft ceased its pathfinding reporting on ad takedowns entirely.

Privacy

American tech giants continue to tout advanced privacy protections. For some (notably Apple), these protections are a primary selling point. On the surface, our leaderboard in this category validates that once again, with Apple, Microsoft, and Alphabet taking the top three places on the podium.

But the landscape of privacy protections offered by U.S. platforms appears largely frozen in time since 2022. Their collective paralysis on this front is even more pronounced than their lack of groundbreaking progress on safeguarding freedom of expression. It also contrasts with vigorous improvements by companies like Samsung, which made by far the greatest leap forward on privacy of any company in 2025.

To be sure, there are bright spots. In late 2023, Meta began rolling out end-to-end encryption (E2EE) by default on Messenger and Instagram chats. The two services followed in the footsteps of WhatsApp, which has used E2EE by default since 2016. The watershed policy change, first signaled several months prior, means that neither third parties nor Meta itself should be able to read or obtain private conversations. Most digital rights groups celebrated the update, even as it thrust the long-standing divide between privacy advocates and law enforcement (backed by children’s rights groups) back into the spotlight. Meta, whose user base across all platforms reached nearly 3.5 billion in 2025, added its weight to the side of the scale that warns against pervasive surveillance and the dire repercussions of granting third parties backdoor access to private communications.

Progress in other areas over the past three years has been far more halting and uneven. Alphabet (Google) and Microsoft both improved slightly, with the former shedding more light on its security audits and red-teaming practices while the latter reinforced its policies on data breaches in 2024, a year of catastrophic data heists. Amazon gave users more control over the geolocation features of Alexa, its virtual assistant, and expanded its ad policies to explicitly cover Alexa.

Yet, much like with government censorship demands, disclosures on government demands for user data did not move an inch from where they were in 2022. The only movement was the silent implosion of X’s long-standing transparency on the topic. Public awareness of security protocols also suffered a hit as Apple retracted previous assurances that it closely monitored employee access to user information.

The pervasive inertia and erosion create significant risk. As generative AI crawlers scrape every corner of the internet for data with no regard to the consent of those who produce it, users’ ability to control their own information has deteriorated. Civil society groups, investors, and people across demographic groups overwhelmingly cite the lack of proper privacy protections and the monetization of personal data as drivers of the erosion of trust in big platforms and the reported “ enshittification” of their services. The incumbent business model of “surveillance capitalism” still reigns supreme, and the U.S. is still the only high-income country with no national privacy law.

Days before this edition of the RDR Index was published, Alphabet (Google) announced that it would abandon its intention to let users opt out of third-party cookies through intuitive prompts. The year prior, it had scrapped its much publicized, but repeatedly delayed, plan to deprecate third-party cookies entirely in favor of stronger privacy protections. When it was first announced in 2020, privacy advocates had lauded the deprecation plan as a seminal development in the history of the internet. Shareholders used RDR data to drum up mainstream support for their acceleration. The tech giant’s ultimate reversal after years of marketing and deferrals encapsulates the findings of the 2025 RDR Index.

Beyond the Benchmark

The 2025 RDR Index paints a picture of timid progress, some paralysis, and one historic decline (X) among the U.S. tech giants. But it is critical to acknowledge what our findings do not (and cannot yet) capture.

First, they do not capture Big Tech’s skyrocketing investments in military and surveillance technology. Monitoring the impacts of this trend is critical, as Silicon Valley has identified the digitalization of war as a boon for its business and a promising market to permeate.

Venture capital firms injected an unprecedented USD 100 billion into defense tech startups between 2021 and 2023. But beyond the startup space, the AI boom and geopolitical chaos have repeatedly turned Big Tech firms into enthusiastic purveyors of warfare as well. Since 2023, large cloud contracts with the Israeli military have facilitated the bombardment of Gaza, and the lure of the market has given Google the incentive to lift its ban on using its AI products for weapons and surveillance. Pioneering projects like Surveillance Watch help shed light on these dynamics.

Second, the findings do not tell us how giant platforms’ practices vary around the world. Their transparency, accountability, and impact on people are not evenly distributed, a reality driven in part by their sources of revenue. The last time Meta reported its annual revenue per person by region, its earnings for users in North America were 14 times greater than those for the regions the company calls “Rest of World.”[5]

Civil society groups commonly argue that these universal disparities lead tech giants to deprioritize Global Majority countries, ignore the harms they contribute to there, and allow hate speech to run rampant on their platforms. Communities who are routinely demonized, criminalized, and targeted by harassment both online and offline echo these sentiments.

While the RDR Index asks for country-by-country reporting in several areas and expects companies to assess discrimination risks, a more complete picture can only emerge from the experiences and efforts of those who understand these impacts first-hand. Dozens of grassroots civil society organizations in many countries have adapted RDR’s methodology to their own settings to accomplish this. In the U.S., GLAAD publishes an annual index tracking how effectively the largest platforms are protecting the rights of LGBTQ users, drawing on the RDR Index. Such distributed, bottom-up initiatives are pivotal to true tech accountability.

Third, the findings do not cover other human rights risks and harms that emanate from Big Tech platforms’ operations, even if those are intimately related to freedom of expression and privacy.[6] These include the labor rights of millions of people in the platforms’ largely invisible global supply chains, from the moderators who review horrific social media content to the annotators and other data workers who prop up generative AI models. Despite years of advocacy and a burgeoning labor movement led by the workers themselves, the ecosystem remains shrouded in secrecy. Tech companies have a notable tendency to use and discard labor, a trend accelerated by rampant automation and profit-oriented market incentives.

Finally, the results do not fully cover the tech giants’ proximity to governments and the power relations that flow from it. Meta and Amazon have been the largest individual corporate lobbyists in the U.S. every year since 2019. U.S. tech companies also represent four of the five biggest lobbying spenders in the EU. Domestically, the crossflow of staff from congressional appropriations entities to Big Tech and back has eroded the boundaries between the two. Under the second Trump administration, the Silicon Valley veterans who quickly permeated government structures also gained unprecedented access to people’s personal data—all without engaging any of the formal processes our methodology assesses.

Only by tackling these and other blind spots can we paint a full picture of Big Tech platforms’ human rights impacts. The relative transparency of U.S. tech giants compared to their counterparts in China and Russia does not guarantee effective human rights safeguards, nor should we assume that it will endure. With the power disparity between Big Tech platforms and their users continuing to grow, it is high time for companies to show how transparency translates into real protections for the people their products are meant to serve.

Footnotes

[1] Microsoft initiated this chain of events in 2011 when it acquired Skype and closed it in 2016 with the purchase of LinkedIn. Facebook mirrored this approach by purchasing Instagram (2012) and later WhatsApp (2014). Twitter, whose role in the industry was comparatively minor, bought the early but influential short-form video platform Vine in 2013. Google’s acquisition of YouTube in 2006 predated all of these shifts.

[2] Google, Apple, Facebook/Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft.

[3] Yahoo, which placed second in 2022, was removed due to its structural misalignment with the World Benchmarking Alliance’s SDG2000 list under its current private-equity ownership. Yahoo was acquired by Apollo Global Management in September 2021; Verizon Group, its previous parent company, retained a 10 percent stake.

[4] These platforms are operated by Amazon (Amazon Store), Apple (App Store), Google (Search, Play Store), Meta (Facebook, Instagram), Microsoft (Bing), ByteDance (TikTok), and X (X.com).

[5] Western Asia and North Africa, Central and South America, and Oceania.

[6] For more research on tech companies’ disclosures on digital inclusion and human rights, see WBA’s Digital Inclusion Benchmark, Corporate Human Rights Benchmark, Social Benchmark, and Gender Benchmark.