While more than half of the companies evaluated in the past two Indexes have made meaningful improvements, they still fall short in disclosing basic information to users about the design, management, and governance of the digital platforms and services that affect human rights.

The Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index measures the minimum disclosure standards that companies should meet in order to demonstrate respect for users’ freedom of expression and privacy rights. Against the backdrop of geopolitical events of the past two years, the Index results highlight four areas of urgent concern:

Governance: Too few companies make users’ expression and privacy rights a central priority for corporate oversight, governance, and risk assessment. Companies do not have adequate processes and mechanisms in place to identify and mitigate the full range of expression and privacy risks to users that may be caused not only by government censorship or surveillance, and by malicious non-state actors, but also by practices related to their own business models.

Security: Companies lack transparency about what they do to protect users’ information. As a result, people do not know the security, privacy, and human rights risks they face when using a particular platform or service. As headlines of the past year have shown, security failures by companies have serious financial, political, and human rights consequences for people around the world.

Privacy: Companies offer weak disclosure of how user information is handled: what is collected and shared, with whom, and under what circumstances. Companies do not adequately disclose how user information is shared for targeted advertising. Such opacity makes it easier for digital platforms and services to be abused and manipulated by a range of state and non-state actors including those seeking to attack not only individual users but also institutions and communities.

Expression: Companies keep the public in the dark about how content and information flows are policed and shaped through their platforms and services. Despite revelations that the world’s most powerful social media platforms have been used to spread disinformation and manipulate political outcomes in a range of countries, companies’ efforts to police content lack accountability and transparency.

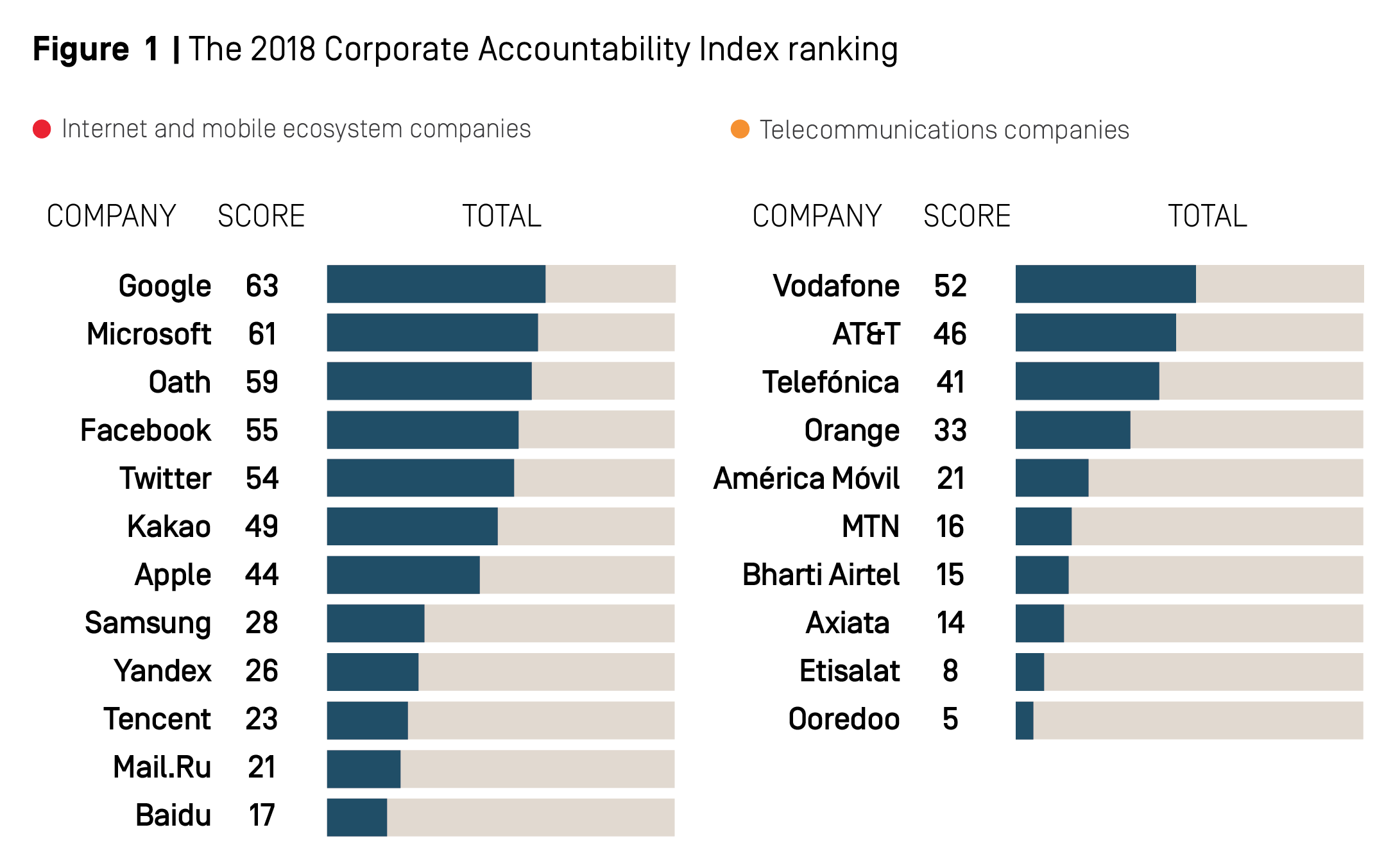

The average score for all 22 companies evaluated in the 2018 Index was just 34 percent. The highest score of any company was 63 percent. It is an understatement to say there is room for improvement: Even companies with higher scores have significant shortcomings in their policies and disclosures.

Research for the 2018 Index was based on company policies that were active between January 13, 2017 and January 12, 2018. New information published by companies after January 12, 2018 was not evaluated in this Index. Note that some of the 2017 Index scores cited in the 2018 Index were adjusted to align with the 2018 evaluation, please see Section 1.4 of this report for more information.

Google and Microsoft kept their lead among internet and mobile ecosystem companies, although the gap is narrowing. Google and Microsoft were the only companies in the entire Index to score more than 60 percent overall, but they made relatively few changes in the past year. These companies’ leading positions are due to the fact that they disclose more information about more policies than all other companies in the Index. Neither company led the pack on every indicator, and both had particular areas in which their poor performance stood out. Microsoft’s overall score actually declined slightly due to a reorganization of some of its information related to Skype (see Figure 2). Google underperformed on governance and ranked near the bottom on one indicator examining disclosure of what user information the company shares and with whom.

Facebook performed poorly on questions about the handling of user data. The company ranked fourth in the Index overall, raising its score by strengthening transparency reporting about lawful requests it receives to restrict content or hand over user data, and improving its explanation about how it enforces terms of service. However, Facebook disclosed less about how it handles user information than six other internet and mobile ecosystem companies (Apple, Google, Kakao, Microsoft, Oath, and Twitter). Most notably, Facebook disclosed less information about options for users to control what is collected about them and how it is used than any other company in the Index, including Chinese and Russian companies (see Chapter 5).

Vodafone shot ahead of AT&T among telecommunications companies after making stronger efforts to demonstrate respect for users’ rights. Vodafone is now the only telecommunications company in the Index to score above 50 percent. The company made meaningful improvements in several areas, notably on stakeholder engagement and due diligence mechanisms. It also improved its disclosure of how it responds to network shutdown demands, and how it handles data breaches. AT&T’s score improvements were due primarily to new disclosure of how it responds to network shutdown orders from authorities, and improved disclosure of options users have to obtain their own data. Its governance score, however, dropped due to its decision not to join the Global Network Initiative (GNI) along with other former members of the now defunct Telecommunications Industry Dialogue.

See each company’s individual “report card” in Chapter 10 of this report.

Most companies evaluated in the Index made progress over the last year: 17 of the 22 companies showed improvement.

Apple saw the greatest score increase among internet and mobile ecosystem companies, gaining eight percentage points in the 2018 Index. Much of this was due to improved transparency reporting. Apple also published information about policies and practices that were already known by industry insiders and experts but had not been disclosed on the official company website. Nonetheless, Apple still lagged behind most of its peers due to weak disclosure of corporate governance and accountability mechanisms, as well as poor disclosure of policies affecting freedom of expression.

.png)

Baidu and Tencent, the Chinese internet companies in the Index, both made meaningful improvements. Baidu made notable improvements to its disclosure of what user information it collects, shares, and retains. Tencent (which kept its substantial lead over Baidu) also made improvements to its disclosure of privacy, security, and terms of service policies. In the 2017 Index, we published an analysis of the Chinese company results and identified areas where these companies can improve even within their home country’s challenging regulatory and political environment.[18] The 2018 Index results showed that Chinese companies can and indeed do compete with one another to show respect for users’ rights in areas that do not involve government censorship and surveillance requirements.

For details on year-on-year changes for each company, see: https://rankingdigitalrights.org/index2018/compare.

Telefónica earned the biggest score change in the telecommunications category. The company increased its governance score by almost 20 percentage points by joining GNI and strengthening its corporate-level commitments, mechanisms, and processes for implementing those commitments across its business. Its overall score was further boosted by improvements to its transparency reporting on government and private requests to block content and for user information.

Many companies continued to improve their transparency reporting. In addition to Apple and Telefónica cited above, a number of other companies also made significant improvements in disclosing process information as well as data on government requests they received and complied with to restrict or block content, to shut down services, or to hand over user data. Facebook improved disclosure of its process for responding to third-party requests to restrict content or accounts, and it reported new data on private requests for the same. Twitter clarified which services its transparency reporting data applies to. Oath and Orange both improved disclosure of data about third-party requests for user information. All three European telecommunications companies—Orange, Telefónica, and Vodafone—plus AT&T, improved their disclosure of circumstances under which they comply with network shutdowns.

Despite these areas of progress, there is persistent lack of improvement in many areas. Chapters 4-7 focus on areas in which we have seen the least improvement: Chapter 4 examines the lack of transparency about security policies and practices; Chapter 5 highlights failure to disclose basic information about the collection, use, and sharing of user data by internet and mobile ecosystem companies; Chapter 6 examines continued opacity around the policing of content by internet platforms and mobile ecosystems; Chapter 7 analyzes the transparency shortfalls and challenges specific to telecommunications companies.

Companies are inconsistent and uneven in anticipating and mitigating risks and harms to users.

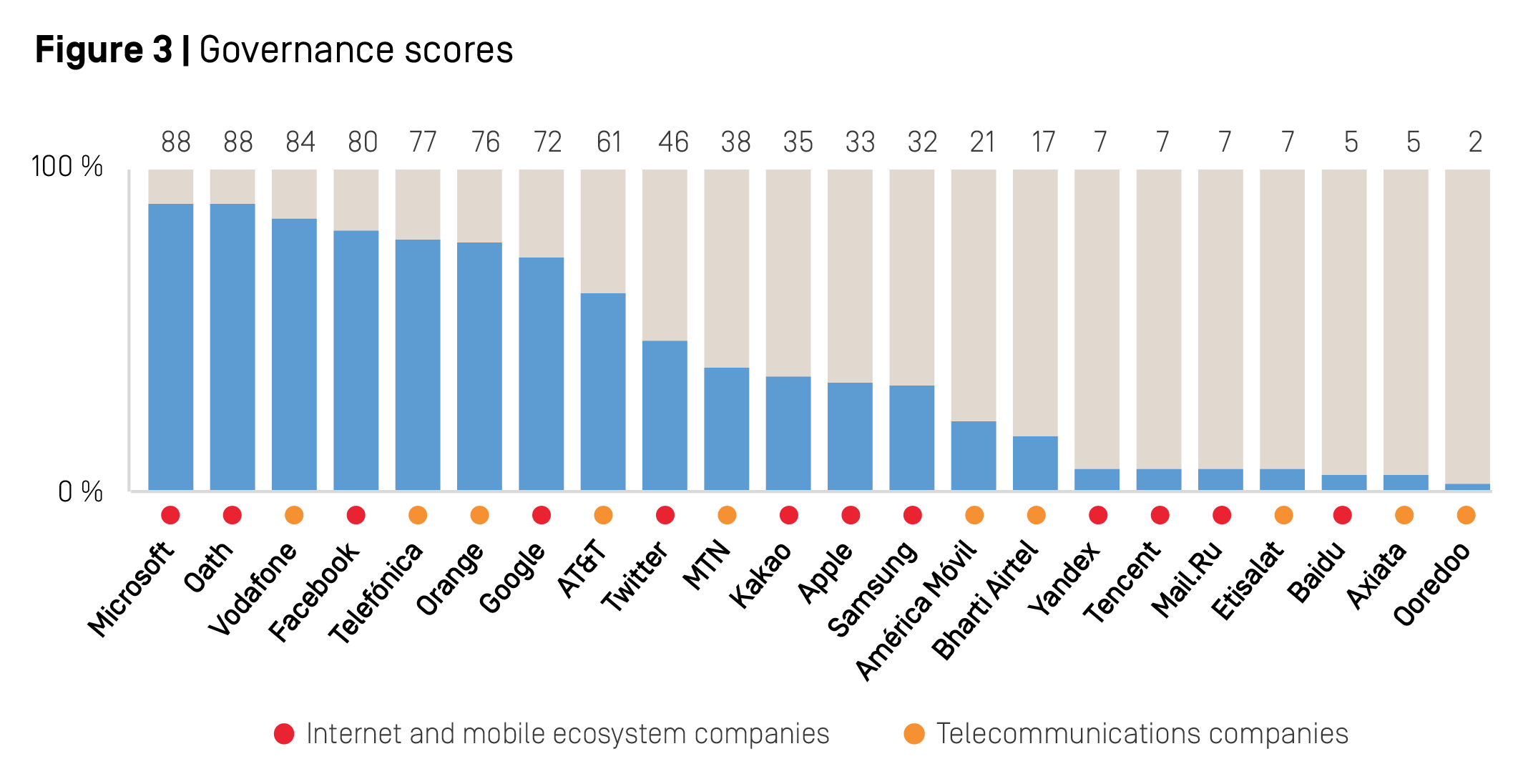

Strong governance and oversight are vital if companies are to anticipate and mitigate potential negative implications of their business and product decisions. Fortunately, many companies are actively working to improve in this area: this category of the Index saw the greatest overall score increase.

The Governance category of the Index evaluates whether companies demonstrate that they have processes and mechanisms in place to ensure that commitments to respect human rights, specifically freedom of expression and privacy, are made and implemented across their global business operations. In order to perform well in this section, a company’s disclosed commitments and measures taken to implement those commitments should at least follow, and ideally surpass, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights[19] and other industry-specific human rights standards focused on freedom of expression and privacy such as the Global Network Initiative Principles.[20] Specifically, measures should include board and corporate-level oversight, internal accountability mechanisms, risk assessment, and grievance mechanisms.

Companies with governance scores of higher than 70 percent were all members of the Global Network Initiative (GNI), a multistakeholder initiative focused on upholding principles of freedom of expression and privacy in relation to government requests. GNI member companies commit to a set of principles and Implementation Guidelines, which include due diligence processes as well as transparency and accountability mechanisms.[21] GNI also requires members to undergo an independent third-party assessment to verify whether they are implementing commitments in a satisfactory manner. The assessment results must then be approved by a multi-stakeholder governing board that includes human rights organizations, responsible investors, and academics, in addition to company representatives.

Companies with the most improved governance scores were Telefónica, Orange, and Vodafone, each of which joined GNI as full members in March 2017, and took measures to improve company commitments, oversight mechanisms, and due diligence in alignment with GNI implementation guidelines.

See Chapter 7 for a more detailed analysis of how telecommunications companies performed in the Index.

AT&T was the only non-GNI company with a governance score of more than 50 percent. However, the company’s score in this category declined due to its weakened commitment to engaging with stakeholders on digital rights issues as a result of its decision not to join GNI along with its European peers and other members of the now-defunct Telecommunications Industry Dialogue.[22] While Apple and Twitter made meaningful improvements in the Governance category, their disclosed oversight and due diligence mechanisms were uneven, with many more gaps in their policies than GNI-member companies.

The greatest disparity in governance scores between GNI and non-GNI companies could be seen on Indicator G4. This indicator examines whether companies carry out regular, comprehensive, and credible due diligence, such as human rights impact assessments, to identify how all aspects of their business affect freedom of expression and privacy and to mitigate any risks posed by those impacts. There is a precipitous drop in disclosure from the top seven companies on this indicator, all GNI members who have made due diligence commitments, and Apple, the highest scoring non-GNI member with only 17 percent.

.png)

Human rights impact assessments (HRIAs) are a systematic approach to due diligence. A company carries out these assessments to determine how its products, services, and business practices affect the freedom of expression and privacy of its users. Such assessments should be carried out regularly. More targeted assessments should also be conducted to inform decisions related to new products, features, and entry into new markets.

While many companies in the Index that conduct HRIAs have shown some improvements over the past year, few conduct truly comprehensive due diligence on how all of their products, services, and business operations affect users’ freedom of expression and privacy. Furthermore, companies that do conduct HRIAs mainly focus on privacy risk assessments and risks related to government censorship and surveillance demands. There is a notable lack of evidence (except from Oath) that companies conduct impact assessments on how their own terms of service rules and enforcement processes affect users’ freedom of expression.

As discussed in Chapter 6, it is fair to expect companies to set rules prohibiting certain content or activities—like toxic speech or malicious behavior. However companies’ commercial practices can have human rights implications that companies have a responsibility to understand and mitigate. For example, human rights activists have complained that thousands of videos uploaded to Google’s YouTube by Syrian activists documenting alleged war crimes were removed removed because they violated rules against violent content.[23] In Myanmar, where access to Facebook via mobile phones is easier and less expensive than accessing other online websites and platforms, Rohingya activists fighting hate crimes and genocide have no alternative platform through which to reach their intended audience.[24] These companies should be conducting human rights impact assessments on how their terms of service enforcement mechanisms affect their users’ ability to exercise and advocate for their rights. Yet neither Facebook nor Google provides any evidence that they in fact carry out such due diligence, though they do disclose that they conduct HRIAs in relation to government censorship and surveillance demands.

For more information about human rights impact assessments and links to a list of resources with practical guidance for companies, please visit: https://rankingdigitalrights.org/2018-indicators/#hria.

The 2018 Index did not look for disclosure about HRIAs on other aspects of companies’ business models and product design, such as how user information is shared with advertisers and marketers, how targeted advertising is managed, how algorithms are used to organize and prioritize the display of content, or how artificial intelligence is deployed. When it becomes apparent that a process or technology has the potential to cause or facilitate violation of human rights, companies should be proactive in using HRIAs to identify and mitigate that harm. One laudable example not accounted for in the 2018 Index methodology is Microsoft’s HRIA process on artificial intelligence technology, launched in 2017.[25] Adjustments to the Index methodology will be considered for future iterations so that companies which are proactive in anticipating and mitigating risks of emerging technologies will be appropriately rewarded, while failures to assess and mitigate known harms stemming from business processes and design choices may also be taken into account as appropriate.

Law, regulations, and political environments have a clear impact on companies’ Index performance.

Governments compel companies to take actions for reasons of public order and national security that can sometimes clash with international human rights norms. Some governments also impose legal requirements, such as data protection laws, that bolster corporate protection and respect for users’ rights when coherently implemented and enforced.

Companies evaluated in the Index operate across a global patchwork of regulatory and political regimes. Most national governments fall short, to varying degrees, of their duty to protect citizens’ human rights. All companies in the Index face some legal or regulatory requirement in their home jurisdiction that prevents them from earning a perfect score on at least one indicator.

The companies at the bottom end of the Index face the greatest legal and regulatory obstacles in the jurisdictions where they are headquartered. In more restrictive or authoritarian regimes, one can find many legal barriers to disclosing the volume and nature of government requests to shut down networks, or to block or delete content. Yet laws that prevent clear public disclosure about the policing of online speech and denial of internet access can also be found in democracies and OECD countries, despite the fact that most such prohibitions are clearly inconsistent with basic principles of accountable governance. For example, in the UK, under limited circumstances, the law may prevent telecommunications operators from disclosing certain government requests to shut down a network.[26]

Meanwhile, legal interventions in Europe related to data protection and intermediary liability are expected to have significant impact on company respect for users’ rights over the coming year.

Data protection: In May 2018, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) will come into force. For the purpose of the Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index, the most significant impact of the GDPR on corporate business practices pertains to an expanded obligation of companies to disclose information to users.[27] Because research for this Index was completed in January 2018, as companies were still revising their policies and preparing for the GDPR, the findings in this report should not in any way be seen as an evaluation of any company’s GDPR compliance. We expect that the 2019 Index will provide a clearer picture of the impact of the GDPR on company disclosure standards and best practices for handling of user information. However, since the RDR indicators do not fully overlap with the GDPR, future Index results can be taken as a measure of how the GDPR has improved company practices but not as a measure of legal compliance.

Outside of the EU, our legal analysis points to a strong relationship between Kakao’s high scores on several indicators related to the handling of user information and South Korea’s strong data protection regime, which requires companies to adhere to data minimization commitments and also contains strong disclosure requirements about collection, sharing, and use. Several jurisdictions where other Index companies are headquartered still lack adequate data protection laws, and companies headquartered in them tend to disclose no more than the law requires, leading to low privacy scores in the Index.

Increased liability for content: While European privacy regulations have generally been praised as a positive development for protecting internet users’ rights, recent European efforts to hold internet platforms responsible for policing users’ online speech have prompted criticism from human rights experts and advocates over concerns that such measures will lead to increased censorship of legitimate content.[28]

In May 2016, the European Commission announced a Code of Conduct on countering illegal online hate speech, signed on to by Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter, and YouTube (Google), each of which agreed to review requests to remove “illegal hate speech” within 24 hours, reviewing the content against their own terms of service as well as applicable national laws.[29] Germany’s Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG), which came into full effect in January 2018, requires social media companies with more than 2 million registered users in Germany to develop procedures to review complaints and remove illegal speech. “Manifestly unlawful” content must be removed within 24 hours and most other “unlawful” content must be removed within seven days. Companies that fail to comply can be fined up to EUR 50 million.[30]

Civil society groups have criticized the Code of Conduct on countering illegal online hate speech for being overbroad and for incentivizing companies to remove content when in doubt about its legality, thus over-censoring content and making violations of users’ free speech rights inevitable.[31] Germany’s NetzDG law has also come under fire for giving private companies excessively broad power to adjudicate speech without sufficient judicial oversight or remedy. Human rights groups have also pointed to troubling efforts by other governments to duplicate such measures in jurisdictions where religious, political, and other speech that is protected under international human rights law is deemed “illegal” by domestic legislation.[32]

Against the backdrop of these trends, the 2018 Index results highlight a persistent and widespread lack of transparency by companies around the policing of content—especially about their terms of service enforcement. Indeed, we found that companies that signed on to the Code of Conduct on countering illegal online hate speech have not disclosed sufficient information about what content they have restricted in compliance with the code or any other information about how their compliance processes work.[33] (See Chapter 6 for detailed analysis of these findings.)

Without a strong commitment by companies to be more transparent about how they handle requests by governments and other third parties to restrict content, and about how they enforce their own rules, it will be all the more difficult for users to seek redress when their expression rights are violated in the course of corporate attempts to comply with new regulations and codes of conduct.

Furthermore, in order for users to obtain remedy when their expression rights are violated, they need accessible and effective mechanisms to do so. The 2018 Index found no other substantive improvements in the disclosed grievance and remedy mechanisms by internet and mobile ecosystem companies, despite a steady stream of media reports of activists and journalists being censored on social media.[34]

The individual company report cards pinpoint how jurisdictional factors affect each company’s scores in specific ways. Despite seriously flawed regulatory regimes across the world, Index results pinpoint many specific ways that all companies can improve even with no changes to their legal and regulatory environments.

Do not wait for the law to improve. Do everything possible now to maximize respect for users’ rights. Companies should not wait for laws to be passed that require them to improve their privacy policies, publish transparency reports, improve governance, or carry out due diligence to mitigate risks. All companies in the Index can improve their scores substantially simply by improving policies in accordance with best practice standards articulated in each indicator, to the greatest extent legally possible. Unfortunately, many companies fail to disclose basic information and data that will help users understand the circumstances under which content or access is restricted or who can obtain their personal data, even when the law does not forbid disclosure of much of this information.

Disclose evidence that the company has institutionalized its commitments. It is certainly important for a company’s top executives to express their personal commitment to respect users’ rights. However, such commitments must be clearly institutionalized to ensure that policies are not being applied inconsistently, or do not depend on the tenure of specific individuals. There should be oversight at the board and executive level over how the company’s business operations affect privacy and freedom of expression. This oversight must be accompanied by other measures such as company-wide training and internal whistleblowing mechanisms.

Conduct regular impact assessments to determine how the company’s products, services, and business operations affect users’ expression and privacy. Several companies in the Index conduct different types of human rights impact assessments (HRIAs), a systematic approach to due diligence that enables companies to identify risks to users’ freedom of expression and privacy, and to enhance users’ enjoyment of those rights. While it may be counterproductive for companies to publish all details of their processes and findings in all circumstances, it is important to disclose information showing that the company conducts assessments and basic information about the scope, frequency, and use of these assessments. For such disclosures to be credible, companies’ assessments should be assured by an external third party that is accredited by an independent body whose own governance structure demonstrates strong commitment and accountability to human rights principles. As of 2018, only the Global Network Initiative meets the requirements for such an accrediting organization.

Establish effective grievance and remedy mechanisms. Grievance mechanisms and remedy processes should be more prominently available to users. Companies should more clearly indicate that they accept concerns related to potential or actual violations of freedom of expression and privacy as part of these processes. Beyond this, disclosure pertaining to how complaints are processed, along with reporting on complaints and outcomes, would add considerable support to stakeholder perception that the mechanisms follow strong procedural principles, and that the company takes its grievance and remedy mechanisms seriously.

Clarify for users what types of requests the company will—and will not—consider, and from what types of parties. For example, some companies make clear that they will only accept government requests for user information or to restrict content via specified channels and that they will not respond to private requests. Other companies do not disclose any information about whether they may consider private requests and under what circumstances. Without clear policy disclosure about the types of requests the company is willing to entertain, users lack sufficient information about risks that they are taking when using a service.

Commit to push back against excessively broad or extra-legal requests. Companies should make clear that they will challenge requests that fail to meet requirements of lawful requests, including in a court of law.

Publish comprehensive transparency reports. Companies should publish regular information and data on their official websites that helps users and other stakeholders understand the circumstances under which personal information may be accessed, speech may be censored or restricted, or access to service may be blocked or restricted. Such disclosures should include the volume, nature, and legal basis of requests made by governments and other third parties to access user information or restrict speech. Disclosures should include information about the number or percentage of requests complied with, and about content or accounts restricted or removed under the company’s own terms of service.[35]

Work with other stakeholders including civil society, academics, and allies in government to reform laws and regulations in ways that maximize companies’ ability to be transparent and accountable to users. The sector will benefit—and so will society as a whole—if public trust in ICT companies can be earned through broad commitment and adherence to best practices in transparency and accountability.

Invest in the development of new technologies and business models that strengthen human rights. Collaborate and innovate together with governments and civil society. Invest in the development of technologies and business models that maximize individual control and ownership over personal data and the content that people create.

[18] “Chinese Internet Companies Show Room for Improvement,” Ranking Digital Rights, March 23, 2017, https://rankingdigitalrights.org/index2017/findings/china/.

[19] “Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights,” United Nations, 2011, http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/GuidingPrinciplesBusinessHR_EN.pdf.

[20] “GNI Principles on Freedom of Expression and Privacy,” Global Network Initiative, accessed February 27, 2017, https://globalnetworkinitiative.org/principles/index.php.

[21] “Implementation Guidelines for the Principles on Freedom of Expression and Privacy,” Global Network Initiative, accessed March 26, 2018, http://globalnetworkinitiative.org/implementationguidelines/index.php.

[22] “Telecommunications Industry Dialogue Launches Final Annual Report,” Telecommunications Industry Dialogue, September 21, 2017, http://www.telecomindustrydialogue.org/telecommunications-industry-dialogue-launches-final-annual-report/.

[23] Malachy Browne, “YouTube Removes Videos Showing Atrocities in Syria,” The New York Times, August 22, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/22/world/middleeast/syria-youtube-videos-isis.html.

[24] Thant Sin, “Facebook Bans Racist Word ‘Kalar’ in Myanmar, Triggers Collateral Censorship,” Global Voices, June 2, 2017, https://advox.globalvoices.org/2017/06/02/facebook-bans-racist-word-kalar-in-myanmar-triggers-collateral-censorship/.

[25] “Microsoft Salient Human Rights Issues: Report - FY17,” Microsoft, http://download.microsoft.com/download/6/9/2/692766EB-D542-49A2-AF27-CC8F9E6D3D54/Microsoft_Salient_Human_Rights_Issues_Report-FY17.pdf.

[26] For more information, see sections 252, 253, and 255(8) of the Investigatory Powers Act: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2016/25/section/253/enacted.

[27] “Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation),” (2016), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32016R0679.

[28] David Kaye, “How Europe’s New Internet Laws Threaten Freedom of Expression,” Foreign Affairs, December 18, 2017, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/europe/2017-12-18/how-europes-new-internet-laws-threaten-freedom-expression.

[29] “Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online First Results on Implementation” (European Commission, December 2016) https://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/image/document/2016-50/factsheet-code-conduct-8_40573.pdf.

[30] “Act to Improve Enforcement of the Law in Social Networks (Network Enforcement Act)” (2017), https://www.bmjv.de/SharedDocs/Gesetzgebungsverfahren/Dokumente/NetzDG_engl.pdf and and Ben Knight, “Germany Implements New Internet Hate Speech Crackdown,” DW, January 1, 2018, http://www.dw.com/en/germany-implements-new-internet-hate-speech-crackdown/a-41991590.

[31] “EU: European Commission’s Code of Conduct for Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online and the Framework Decision - Legal Analysis” (Article 19, June 2016), https://www.article19.org/data/files/medialibrary/38430/EU-Code-of-conduct-analysis-FINAL.pdf.

[32] Emma Lux, “Efforts to Curb Fraudulent News Have Repercussions around the Globe,” Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, December 6, 2017, https://www.rcfp.org/browse-media-law-resources/news/efforts-curb-fraudulent-news-have-repercussions-around-globe.

[33] "Factsheet on the Code of Conduct – 3 round of monitoring" (European Commission, January 2018) document available here: http://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/just/item-detail.cfm?item_id=612086.

[34] See for example Olivia Solon, “I Can’t Trust YouTube Any More’: Creators Speak out in Google Advertising Row,” the Guardian, March 21, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/mar/21/youtube-google-advertising-policies-controversial-content and Thant Sin, “Facebook Bans Racist Word ‘Kalar’ in Myanmar, Triggers Collateral Censorship,” Global Voices, June 2, 2017, https://globalvoices.org/2017/06/02/facebook-bans-racist-word-kalar-in-myanmar-triggers-collateral-censorship/.

[35] “Working Group 3: Privacy and Transparency Online” (Freedom Online Coalition, November 2015), https://www.freedomonlinecoalition.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/FOC-WG3-Privacy-and-Transparency-Online-Report-November-2015.pdf.