Internet and mobile ecosystem companies don’t disclose enough about how they handle user information, which makes it difficult to assess the privacy, security, and human rights risks of using their services.

Internet and mobile ecosystem companies collect vast amounts of information about users. This includes the personal information people give companies when signing up for a service as well as the behavioral data they collect by tracking their browsing activities and preferences, location data, and access and login activities and histories. Such information can be shared with different third parties, including governments, courts, and law enforcement, who make legal demands for user data, and with advertisers. Detailed profiles created with users’ information can be used by government agencies to identify surveillance targets, by financial service companies to determine creditworthiness, and by businesses and other organizations (including advocacy groups and political campaigns), which can target people with advertisements and marketing campaigns tailored to their profiles.[48]

Telecommunications companies also lacked disclosure of how they handle user information. See Chapter 7 for a detailed analysis.

While the misuse and exploitation of information people share with companies does not constitute the type of “breach” or theft discussed in the previous chapter on security (because the information was not technically stolen), the potential for harm to individuals and to vulnerable categories of people is nonetheless very real. Failure to assess and mitigate harm constitutes a betrayal of user trust and lack of respect for user rights.

Reacting to revelations that the political research and consulting firm Cambridge Analytica obtained Facebook user data for the purpose of influencing voters in multiple countries, the Internet Society called it “the natural outcome of today’s data driven economy that puts businesses and others first, not users” and called for “higher standards for transparency and ethics when it comes to the handling of our information. Anyone who collects data must be accountable to their users and to society.”[49]

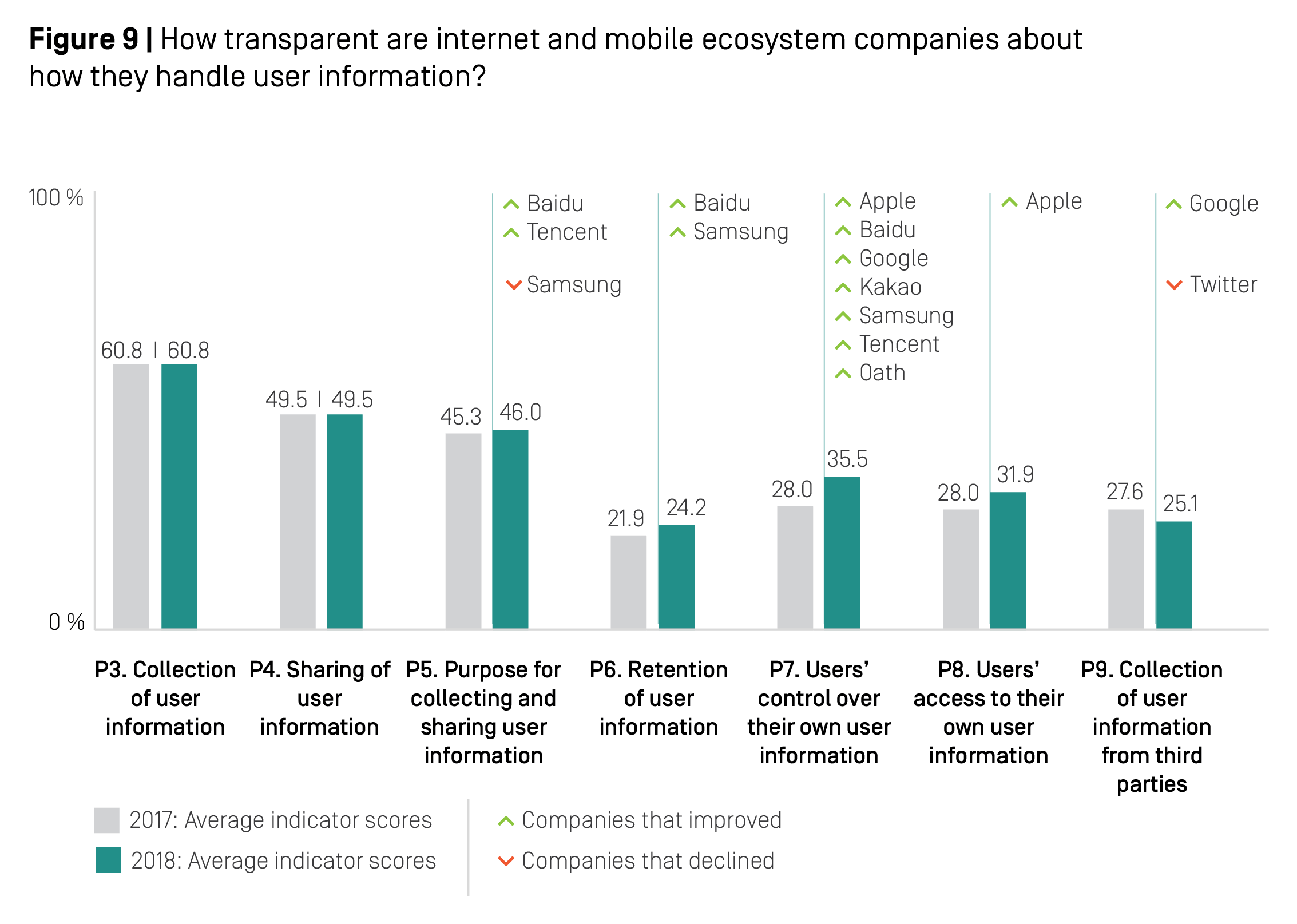

The Index aims to do just that with seven indicators evaluating corporate transparency about handling of user information.[50] We expect companies to disclose what information they collect (P3), what information they share and the types and names of the third parties with whom they share it (P4), for what purpose they collect and share user information (P5), and for how long they retain this information (P6). Companies should also provide clear options for users to control what information is collected and shared, including for the purposes of targeted advertising (P7), and they should clearly disclose if and how they track people across the internet using cookies, widgets or other tracking tools embedded on third-party websites (P9). We expect companies to clearly disclose how users can obtain all public-facing and internal data they hold on users, including metadata (P8).

Yet 2018 Index results show that users remain largely in the dark about what information about them is collected and shared, with whom, and for what purposes.

What do we mean by “user information”? RDR defines “user information” as any information that identifies a user’s activities, including (but not limited to) personal correspondence, user-generated content, account preferences and settings, log and access data, data about a user’s activities or preferences collected from third parties, and all forms of metadata. Companies might have their own definition of user information, which can differ from RDR’s definition of user information and be narrower in scope. For example, a company may define user information as the demographic information a user voluntarily provides upon signing up for a service (e.g., age, gender), but not include automatically collected metadata or other types of information. See the 2018 Index glossary: https://rankingdigitalrights.org/2018-indicators/#userinformation.

Internet and mobile ecosystem companies have made little progress in disclosing how they handle user information, and what options people have to control what is collected and shared.

As Figure 9 illustrates, internet and mobile ecosystem companies have taken few concrete steps to improve in this area. As a result, users still lack the information they need to make informed choices to assess the privacy and human rights risks they face when using a particular service.

As we found in the 2017 Index, companies in the 2018 index still tended to disclose more about what information they collect, and less about how they manage it. Companies in the 2018 index did not sufficiently disclose what user information they share and with whom, for what purposes they collect and share this information, for how long they retain it, and what options users have to control whether information about them is collected and shared.[51]

While some companies made improvements, all internet and mobile ecosystem companies evaluated still lacked sufficient information about what data they collect (P3) and share (P4), for what purpose they collect and share it (P5), and for how long they retain it (P6) (see Section 5.2). Notably, internet and mobile ecosystem companies disclosed little about their data retention policies. While in some jurisdictions they are legally required to retain user information for specific periods, companies should disclose what that time frame is and whether they retain user information for longer than is legally required. Companies also lacked sufficient information about how users can control what companies collect, and targeted advertising continues to be the default setting (P7) (see Section 5.3).

Two companies—Chinese internet companies Baidu and Tencent—improved their disclosure of reasons for collecting and sharing information (P5), but companies on average scored poorly on this indicator.

Seven companies—Apple, Baidu, Google, Kakao, Samsung, Tencent, and Oath—improved their disclosure of options users have to control their own information (P7), but disclosure of these options still remains unsatisfactorily low (see Section 5.3).

Just one company—Apple—improved its disclosure of options users have to access their information (P8).

Google improved its disclosure of whether and how it tracks Android users across the internet (P9), clarifying that it may use tools similar to cookies to present users of mobile applications and browsers with tailored advertising, and explained the reasons for doing so.[52]

Revisions in Twitter’s privacy policy made its policies and practices about its tracking of users across the internet less clear (P9). Notably, Twitter also disclosed it does not respect Do Not Track (DNT) signals that allow users to indicate they do not want to be tracked across the internet (see Section 5.4.

Internet and mobile ecosystem companies don’t disclose enough about what information they are sharing, with whom, or for what purpose.

The Index includes two indicators that evaluate how transparent companies are about their data-sharing policies (P4, P5). Indicator P4 evaluates company disclosure of what user information companies share, including the types and names of third-parties with whom they share it. Indicator P5 evaluates whether and how clearly companies disclose their purpose for collecting and sharing user information.

As shown in Figure 10, most internet and mobile ecosystem companies did not sufficiently disclose what types of information they share and with whom, with only two of the 12 companies scoring more than 50 percent on this indicator (P4). Kakao’s disclosure on this indicator far surpassed all others. Notably, Google and Apple disclosed less about their data-sharing practices than most internet and mobile ecosystem companies evaluated, only scoring higher on this indicator than Mail.Ru and Baidu, which were among the lowest scoring companies in the Index overall.

An examination of element-level data for this indicator (P4) revealed that while all internet and mobile ecosystem companies disclosed a policy of sharing user information with government authorities if requested, they were less transparent about what other types of third parties they share information with and what types of user information they share. Only a handful of companies disclosed the actual names of third parties with whom they share user information, and no company disclosed all the types of user information they share. Likewise, mobile ecosystem companies did not sufficiently disclose whether they review the data-sharing practices of the apps hosted in their app stores.

Internet and mobile ecosystem companies disclosed even less about why they collect and share user information, with an average score of 46 percent on this indicator (P5, Figure 11). However, the order of the ranking on this indicator looks very different than for Indicator P4, with Google and Twitter tied at the top. But their top score of 63 percent leaves much room for improvement. Notably, Facebook disclosed substantially less about reasons for collecting and sharing user information than its U.S.-based peers.

_.png)

An analysis of element-level disclosure on this indicator shows that while many companies disclosed whether they combine user information from different services and the reasons for doing so, fewer disclosed their reasons for collecting and sharing user information. Companies were particularly hesitant to make a clear commitment to using information only for the purposes for which it was collected.

For more information and data:

Users lack clear options to control what companies collect and share about them, including for targeted advertising.

Recent examples of harmful content and misinformation targeted at social media users illustrate that pervasive user tracking not only poses threats to privacy and security, but also to the basic functions of open democracy.[53] Therefore, it is critical that people have control over what information about them is collected and shared, including how this information is used to target them for commercial and political advertising. Targeted advertising involves tracking users extensively and retaining large amounts of information on them.[54] Companies should therefore clearly disclose whether users have options to control how their information is being used for these purposes.

Indicator P7 evaluates company disclosure of what options users have to control what information the company collects on them and uses, including for the purposes of targeted advertising.[55] We expect companies to allow users to control what information is collected about them, which also means enabling users to delete specific types of information without requiring them to delete their entire account. In addition, we expect companies to give users options to control how their information is used for advertising and to disclose that targeted advertising is off by default.

The 2018 Index data showed that most companies failed to disclose clear options for users to control what data about them is collected and how it is used for the purposes of advertising (Figure 12). While a majority of internet and mobile ecosystem companies improved their disclosure on this indicator, disclosure of these options remained insufficient.

Seven companies—Apple, Baidu, Google, Kakao, Samsung, Tencent, and Oath—improved their disclosure of options users have to control their information, which includes options to control if and how their data is collected for targeted advertising (P7) (See company report cards for details.)

Google was the most transparent among internet and mobile ecosystem companies on this particular indicator. In addition to giving users limited options to control the collection of their information and to delete some of this information, the company explained how users can opt out of targeted advertising. However, it appeared from this disclosure that targeted advertising is on by default.

Facebook disclosed the least on this topic. The company did not clearly disclose whether users can control the collection of their information, and it also did not disclose whether users are able to delete some of this information. Despite giving users limited options to control how their information is used for advertising purposes, the company failed to commit to turn off advertising by default.

Twitter disclosed less than Google on this indicator, but was on par with Apple’s disclosure. Twitter disclosed that it allowed users to control the collection of some of their information and delete some of this information, but did not disclose whether this was the case for all types of user information the company collects. Like most other internet and mobile ecosystem companies evaluated, Twitter explained how users can control whether their information is used for advertising purposes, but it did not indicate that interest-based advertising was off by default.

_.png)

User privacy should be the default.

In order to provide users with free services, many internet and mobile ecosystem companies monetize the information they hold about their users. Advertising technologies allow companies and third parties to target users based on profiles derived from this data. Given the significant privacy implications of targeted advertising, companies should provide users with control over how their information is used for targeted advertising. Moreover, companies should not assume that all users have an understanding of the privacy concerns resulting from these advertising practices. Therefore, targeted advertising should be off by default.

What is targeted advertising? Targeted advertising, also known as “interest-based advertising” or “personalized advertising,” refers to the practice of collecting a range of data about individual users—including demographic data, browsing history and preferences, and location information—with the goal of personalizing the ads users see online. Typically, targeted advertising relies on vast data collection practices, which can involve tracking users’ activities across the internet using cookies, widgets, and other tracking tools, in order to create detailed user profiles. What do we mean by opting out versus opting in? “Opt-in” means the company does not collect, use, or share data for a given purpose until users explicitly signal that they want this to happen. “Opt-out” means the company uses the data for a specified purpose by default, but will cease doing so once the user tells the company to stop. For more, see Dipayan Ghosh and Ben Scott, “Digital Deceit: The Technologies Behind Precision Propaganda on the Internet,” New America, January 2018, https://www.newamerica.org/public-interest-technology/policy-papers/digitaldeceit/.

Despite significant public concerns regarding the invasive nature of of social media platforms’ advertising tools, Facebook provided users with only limited options to control the use of their information for targeted advertising. Furthermore, for both Facebook, the social networking platform, and Facebook’s Messenger service, the company disclosed that it may always use information such as age and gender to present users with advertising.[56]

Mail.Ru disclosed slightly more than Facebook regarding the options users have to control the collection of their information and to delete some of it. At the same time, the Russian company was the only internet and mobile ecosystem company not to reveal anything about how users can control the use of their information for advertising purposes.

Most internet and mobile ecosystem companies clearly disclosed at least some options users have to control how their information is used for targeted advertising, implying it is on by default. None disclosed that targeted advertising was off by default.

All mobile ecosystems—Apple iOS, Google Android, and Samsung’s Android—disclosed options to control location tracking.

Geolocation data collection is critical to the functionality of many mobile applications, but it can also raise significant concerns for user privacy. This information is particularly sensitive as many users take their devices wherever they go, oftentimes not keeping in mind that they are being tracked. For those who are part of vulnerable communities, including journalists, sexual minorities, and human rights activists, location data tracking can also result in physical harm.

For these reasons, we expect companies to disclose that users can control geolocation data tracking. Users should be able to control geolocational data tracking at the device level, as well as on an app-by-app basis. This enables them to determine whether device manufacturers and individual applications can access this data. All three mobile ecosystems evaluated in the 2018 Index clearly disclosed options for users to turn off geolocation data collection. While Apple and Google provide user control at both the device level and on an app-by-app basis, Samsung only disclosed how users can control this information at the device level.

Most internet and mobile ecosystem companies don’t disclose if and how they track people across the web.

Internet and mobile ecosystem companies not only collect information about what people do when using their services, but they also track users’ web browsing activities. Indicator P9 evaluates how transparent internet and mobile ecosystem companies are about these practices, looking for companies to disclose if, how, and why they track people across third-party websites.[57] We expect companies to disclose what types of information they collect via cookies, widgets, and other types of trackers, the purposes for doing so, and how long they retain this information. We also expect companies to disclose if they respect “Do Not Track” signals, which allow users to tell companies not to collect or store information about their visits to or activities on third-party websites.[58]

Results of the 2018 Index show that all companies other than Apple lacked sufficient disclosure regarding whether and how they track users across the internet (Figure 13). Apple was the only company that clearly stated it does not track users on third-party websites. The remaining 11 internet and mobile ecosystem companies in the Index either lacked clear disclosure about their tracking practices or provided no information at all.

![]()

Google made slight improvements to its disclosure by more clearly explaining how it tracks users of the Android mobile ecosystem. It clarified that it may use tools similar to cookies to present users with targeted advertising, and it explained reasons for doing so.

Twitter became less transparent about how long it retains the information it collects by tracking users and its purposes for collecting it.

Facebook’s disclosure of user tracking on third-party sites and services was also unclear. For Facebook, the social network, and Messenger, the company disclosed what information it collects about users on third-party websites with tracking tools like cookies and widgets, but it did not disclose the purpose for doing so, or for how long it retains this information. For Instagram and WhatsApp, Facebook did not disclose whether, how, or for what purpose it tracks users on third-party websites.

None of the companies disclosed that they respect user-generated signals to opt out of data collection. Three companies—Microsoft, Oath and Twitter—explicitly stated they do not respect “Do Not Track” signals from users asking companies not to track them across the web.[59] The remaining companies did not indicate whether they respect such signals.

Baidu and Mail.Ru were among several companies that did not provide any information on whether they track users across the web.

Maximize user control over their own data. Companies should not only provide clear disclosure of how they handle user information, but also give users clear options to control what information is collected and shared and with whom. This should also include user control over whether their information is combined from different company services.

Ensure transparency around handling of user information. Companies should clearly disclose how they handle users’ information, including what information is collected and shared, as well as the purposes for doing so. Companies should disclose:

what specific types of information they collect (P3);

how that information is collected (e.g., does a company ask users to provide certain information, or does the company collect it automatically?) (P3);

what information is shared and with whom (P4);

why they collect and share that information (P5);

how long the information is retained (P6);

whether and how the that information is destroyed when users delete their accounts or cancel their service (P6);

whether—and the extent to which—users can control what information about them is collected and used (P7); and

whether users can access all public- facing and private information a company holds about them (P8).

Tell users whether and how they are tracked. Companies should clearly disclose whether and how they collect user information from third-party sites and services.

Facilitate user access to their information. Users should have the ability to obtain all the information a company holds about them, and to download it in a format that allows them to transfer some or all of this data into a new service, if they wish to do so.

User privacy should be the default. Companies should not assume that users are aware of the connection between data collection and targeted advertising, and targeted advertising should be off by default.

Respect user preferences. Companies should support the development of a viable system for users to indicate they do not want to be tracked across the internet, and make a clear commitment to respect these preferences.

Build partnerships for stronger user privacy. Companies should proactively and systematically engage with researchers, engineers and advocates to ensure company policies and practices reflect privacy best practices.

Privacy innovation. Invest in the development of technologies and business models that maximize user control over their personal information and content.

[48] Ghosh, Dipayan and Ben Scott, “Digital Deceit: The Technologies Behind Precision Propaganda on the Internet,” New America, January 2018, https://www.newamerica.org/public-interest-technology/policy-papers/digitaldeceit/.

[49] “Sorry Just Isn’t Enough. Businesses Must Do Better When It Comes To People’s Data,” Internet Society, March 23, 2018, https://www.internetsociety.org/news/statements/2018/sorry-just-isnt-enough-businesses-must-better-comes-peoples-data/.

[50] See the 2018 Index methodology at: https://rankingdigitalrights.org/2018-indicators/.

[51] See Chapter 6, 2017 Corporate Accountability Index, Ranking Digital Rights, https://rankingdigitalrights.org/index2017/assets/static/download/RDRindex2017report.pdf/.

[52] See the "Advertising identifiers on mobile devices" section of Google’s Advertising page for more information: “Advertising,” Google Privacy & Terms, accessed March 23, 2018, https://www.google.com/policies/technologies/ads/.

[53] Recent examples illustrate how advertising tools on social media have been exploited to spread disinformation during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections and the Brexit referendum: “Russian Twitter Trolls Meddled in the Brexit Vote. Did They Swing It?,” The Economist, November 23, 2017, https://www.economist.com/news/britain/21731669-evidence-so-far-suggests-only-small- campaign-new- findings-are-emerging-all/.Alex Hern, “Facebook Enables ‘fake News’ by Reliance on Digital Advertising – Report,” The Guardian, January 31, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jan/31/facebook-fake-news-disinformation-digital-advertising-report-news-feed](https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jan/31/facebook-fake-news-disinformation-digital-advertising-report-news-feed/.Researchers have similarly shown how these tools can be used by white supremacists to spread hateful messages against Jewish and Muslim communities: Will Oremus and Bill Carey, “Facebook’s Offensive Ad Targeting Options Go Far Beyond ‘Jew Haters,’” Slate Future Tense, September 14, 2017, http://www.slate.com/blogs/future_tense/2017/09/14/facebook_let_advertisers_target_jew_haters_it_doesn_t_end_there.html/

[54] Ghosh, Dipayan and Ben Scott, “Digital Deceit: The Technologies Behind Precision Propaganda on the Internet,” New America, January 2018, https://www.newamerica.org/public-interest-technology/policy-papers/digitaldeceit/.

[55] See the 2018 Index methodology at: https://rankingdigitalrights.org/2018-indicators/#P7/.

[56] See more information on this Facebook help page: “How Does Facebook Decide Which Ads to Show Me and How Can I Control the Ads I See?,” Facebook Help Center, accessed March 20, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/help/562973647153813?helpref=faq_content/.

[57] See the 2018 Index methodology at: https://rankingdigitalrights.org/2018-indicators/#P9.

[58] See the Index 2018 Index glossary at: https://rankingdigitalrights.org/2018-indicators/#DoNotTrack.

[59] See Twitter’s disclosure: “Do Not Track,” Twitter Help Center, accessed March 26, 2018, https://help.twitter.com/en/safety-and-security/twitter-do-not-track.