Across the world, a small number of internet platforms, mobile ecosystems, and telecommunications services have become powerful gatekeepers for public discourse and access to information. As discussed in Chapter 3, Facebook, Google (YouTube), and Twitter lack oversight and risk assessment mechanisms that could help them identify and mitigate the ways that their platforms can be used by malicious actors to organize and incite violence or manipulate public opinion. A growing body of research and scholarship has shown how these problems are exacerbated by companies’ design choices and or business models.46

The concentrated power of a handful of companies over billions of people’s online speech and access to information is causing major new social, political, and regulatory challenges to nations and communities across the world. Yet these challenges do not diminish the vital importance of freedom of expression as a fundamental human right, upon which the defense of all other rights against abuses of political and economic power ultimately depends.

Companies and civil society have documented a rapid global increase in government demands for companies to restrict and block online speech, and for telecommunications companies to throttle or even shut down internet access. Human rights law does allow for restriction of speech in a “necessary and proportionate” manner. But even democratic governments have made censorship demands of companies that fail to meet this test, which has resulted in censorship of journalists, activists, and speech by religious, ethnic, and sexual minorities.47

For a discussion of recent regulatory trends and challenges, see section 4.5.

How should speech be governed across globally networked digital platforms and services in a manner that supports and sustains all human rights? Solving this problem will require innovation and cooperation by and among governments, industry, and civil society, grounded in a shared commitment to international human rights principles and standards. At a time when the regulatory landscape is changing fast and in ways that threaten freedom of expression, it is vital that companies implement maximum transparency about how, why, and by whom online speech and access to information is shaped and controlled. Companies can and must do better.

Transparency about how companies, governments, and other entities influence and control online expression remains inadequate.

Freedom of expression online can be restricted in a number of ways. A government can make direct demands of companies that content be removed or blocked, that a user’s account be deactivated or restricted, that entire applications be removed from an app store or blocked by an internet service provider, or that entire networks be shut down. Private organizations or individuals can use legal mechanisms such as copyright infringement notices or “right to be forgotten” claims in the European Union. Companies also restrict speech when they enforce their own private terms of service. People’s rights to freedom of expression are violated when a country’s laws governing speech are not in alignment with international human rights standards, when government officials abuse power to censor without oversight, when enforcement is overbroad, or when individuals abuse legal mechanisms intended for the protection of their own rights to silence critics.48

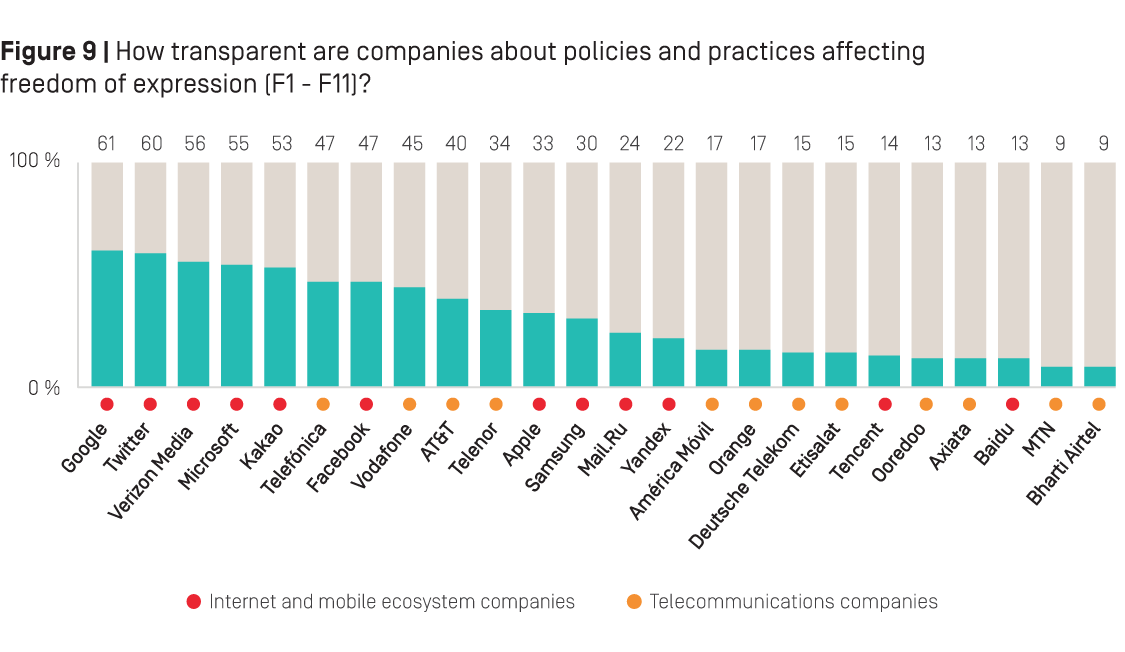

The Freedom of Expression category of the RDR Index expects companies to disclose their policies and practices affecting users’ speech, including how they respond to government and other types of third-party demands, as well as how they determine, communicate, and enforce private rules and commercial practices that affect users’ freedom of expression.

Evaluating how transparent companies are about policies and practices affecting freedom of expression What the RDR Index evaluates: The RDR Index evaluates company disclosure of policies and practices affecting freedom of expression across 11 indicators. Indicators assess:

- Accessibility and clarity of terms: Does the company provide terms of service that are easy to find and understand? Does the company commit to notify users when they make changes to these terms (F1, F2)?

- Content and account restrictions: How transparent is the company about the rules and its processes for enforcing them (F3-F4)? Do companies inform users when content has been removed or accounts have been restricted, and why (F8)?

- Government and third-party demands: How transparent is the company about its handling of government and other types of third-party requests to restrict content or accounts (F5-F7)?

- Network management and shutdowns (for telecommunications companies): Does the company commit to practice net neutrality (F9)? Does the company disclose its process for handling government requests to shut down a network (F10)?

- Identity policies: Does the company require users to verify their identities with a government-issued ID (F11)?

To review the freedom of expression indicators, see: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#F

Companies’ average overall performance in the Freedom of Expression category increased only slightly between 2018 and 2019. This means that internet users still lack adequate information about how their speech or access to information may be restricted, by whom, under what authority or circumstances.

A handful of internet companies took major steps forward in boosting transparency about the volume and nature of content and accounts that were deleted or restricted when enforcing their own terms of service. Google boosted its overall freedom of expression score primarily for this reason (see section 4.2). Yet others took steps backward that exceeded their steps forward. While Facebook made some significant improvements in transparency about terms of service enforcement, as will be discussed below, its overall freedom of expression score nonetheless declined due to decreased transparency in relation to third-party and government demands. One telecommunications company, Telefónica, made major strides in transparency about government and third-party demands affecting users’ freedom of expression in particular. But with the exception of slight improvements by MTN and Axiata, all other telecommunications companies were either stagnant or backtracked. Notably, Vodafone, which ranked high overall and improved in the other categories, backtracked slightly in freedom of expression due to reduced clarity about its rules and their enforcement.

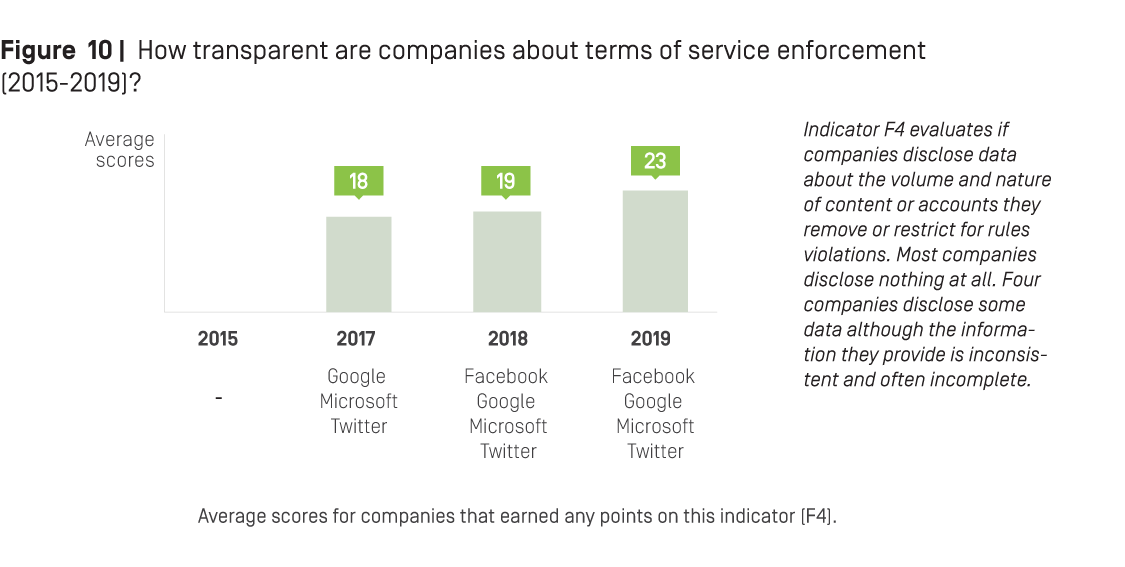

While a few companies took laudable steps by publishing data about the volume and nature of content removed for violating terms of service, none disclosed enough about their rules or actions taken to enforce them—and most disclosed nothing.

When the inaugural RDR Index launched in 2015, no company received any credit on the indicator measuring whether they regularly publish data about the volume and nature of actions taken to restrict content or accounts that violate the company’s rules (F4).

Evaluating how transparent companies are about actions they take to enforce their terms of service

What the RDR Index measures: Indicator F4 of the RDR Index evaluates if companies clearly disclose and regularly publish data about the volume and nature of actions taken to restrict content or accounts that violate the company’s rules.

- Element 1: Does the company clearly disclose data about the volume and nature of content and accounts restricted for violating the company’s rules?

- Element 2: Does the company publish this data at least once a year?

- Element 3: Can the data published by the company be exported as a structured data file?

Read the guidance for Indicator F4 of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#F4

While most companies in the RDR Index still failed to earn any credit on this indicator, three companies—Facebook, Google, and Twitter—made significant strides by publishing comprehensive data about content removals due to terms of service enforcement, while another company, Microsoft, published some information, albeit in a less systematic manner.

Facebook, Google, and Twitter all published more data about content removals due to terms of service enforcement than they had previously. In May 2018, Facebook published a new Community Standards Enforcement Report with more comprehensive data on terms of service enforcement for the social network. Shortly before that, in April 2018, Google released its first Community Guidelines Enforcement Report for YouTube, with more comprehensive data regarding the nature and volume of removals due to terms of service enforcement. Twitter took a step forward by publishing, in December 2018, a single, comprehensive report focused on terms of service enforcement, which included data on the number of accounts it took action against and for what category of violation.

Despite publishing more structured and comprehensive transparency reports, Facebook’s and Google’s scores on this indicator—which are calculated by averaging scores across several services—ended up lower than Microsoft’s, which published less comprehensive data but was more consistent across services. Facebook scored lower than Microsoft because its new Community Standards Enforcement Report applied just to Facebook (the social network) and not to Instagram, WhatsApp, or Messenger. Similarly, Google’s new report applied only to YouTube. Twitter lost points for not supplying the data in a structured format, and because it was not clear if the company plans to regularly publish this data.

The RDR Index has three other indicators that evaluate how clear companies are about their rules and enforcement processes: if their terms are easy to find and to understand (F1), if they disclose whether they notify users of changes (F2), and if they disclose sufficient information about what types of content or activities are prohibited and how these rules are enforced (F3).

While five companies—Axiata, Facebook, Google, MTN, and Verizon Media—improved the accessibility of their terms of service, Ooredoo and Yandex showed declines. (For Yandex terms were no longer easy to find and for Ooredoo not all terms for all services were available in the home market’s primary languages.) Five companies—Facebook, Microsoft, MTN, Verizon Media, and Twitter—clarified the way they notify users when they change their terms of service, but Vodafone’s score declined since its postpaid mobile terms no longer disclosed a time frame for notifying users of changes.

Telenor disclosed more information than any other telecommunications company about its rules and how they are enforced (F3). However, it should be noted that this is the only indicator on which all companies in the RDR Index received at least some credit. All companies published terms of service that included at least basic information about prohibited activities or content, such as rules against using their services to violate copyright laws or to harass or defame others. Companies based in jurisdictions where the law explicitly bans certain types of speech also tend to list these prohibited activities and content in their terms of service. It is for this reason, primarily, that Qatar-based Ooredoo—which placed last in the entire RDR Index—earned points in the Freedom of Expression category for disclosures about the content and enforcement of its rules, while earning no credit in either the Governance or Privacy categories.

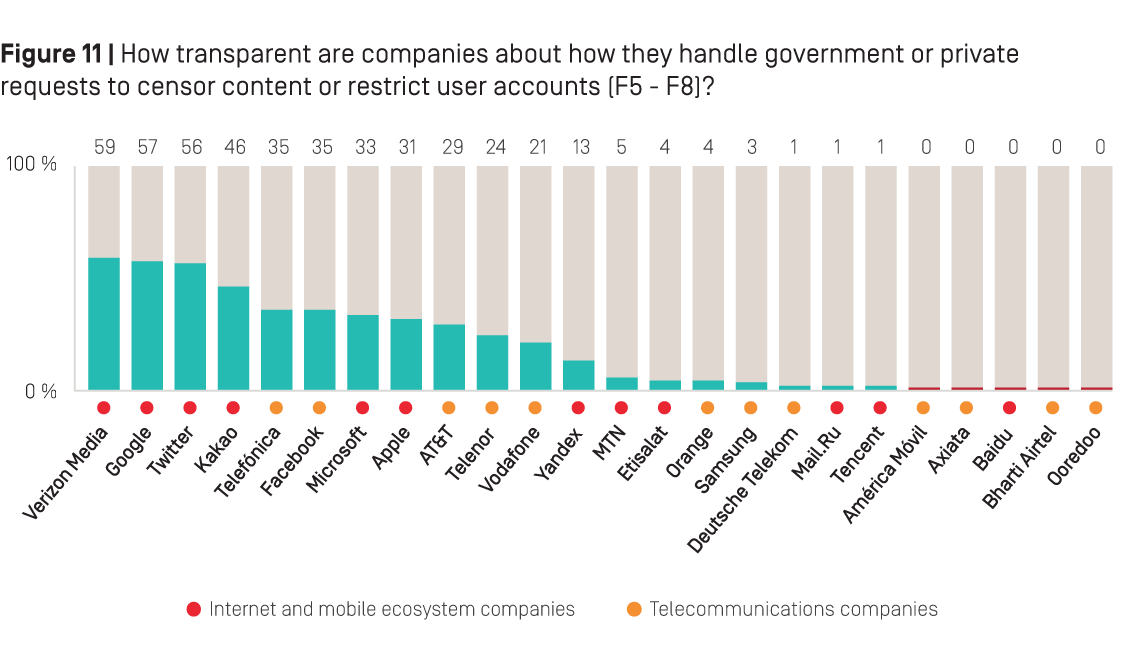

Beyond specific and notable improvements, most companies lack transparency about how they handle formal government demands and private requests to censor content or restrict accounts.

Ten companies in the RDR Index produce transparency reports containing data about the volume and nature of government demands to remove or restrict online speech. Most of these reports show an increase in government demands over the past two years. For example: Twitter’s most recent transparency report, covering government requests to remove content from January to June 2018, found that it had “received roughly 80% more global legal demands impacting approximately more than twice as many accounts, compared to the previous reporting period.”49 Google’s most recent transparency report shows that between June 2016 and June 2018, the number of requests received more than tripled.50 Unfortunately, corporate transparency about the volume and nature of such demands is not improving as demands grow, and, in some cases, transparency is declining.

While Facebook and Twitter made significant efforts to disclose more data related to terms of service enforcement as described in the previous section, both actually provided less comprehensive data about government requests to remove, filter, or restrict accounts or content than they did in 2018 (F6). Facebook’s transparency report no longer clarified if the data included information about WhatsApp or Messenger, and Twitter no longer included as much detail about requests received related to its video service, Periscope. Facebook’s disclosure of its process for responding to third-party requests for content or account restriction (F5) also lacked clarity about what services its process covers. While Twitter’s overall score on this indicator improved due to new information that it carries out due diligence and will push back on inappropriate demands, it also failed to clarify whether this policy applied to Periscope as well as its main social networking platform (F5).

On the positive side of the equation: Apple published more accessible data about government requests to remove or restrict accounts—which was Apple’s only improvement in the Freedom of Expression category. But the company still offered no information about requests to remove content (F6).

How does RDR define government and private requests?

Government requests are defined differently by different companies and legal experts in different countries. For the purposes of the RDR Index methodology, all requests from government ministries or agencies, law enforcement, and court orders in criminal and civil cases, are evaluated as “government requests.” Government requests can include requests to remove or restrict content that violates local laws, restrict users’ accounts, or to block access to entire websites or platforms. We expect companies to disclose their process for responding to these types of requests (F5), as well as data on the number and types of such requests they receive and with which they comply (F6).

Private requests are considered, for the purposes of the RDR Index methodology, to be requests made by any person or entity through processes that are not under direct governmental or court authority. Private requests can come from a self-regulatory body such as the Internet Watch Foundation, through agreements such as the EU’s Code of conduct on countering illegal hate speech online, from individuals requesting to remove or de-list content under the “Right to be Forgotten” ruling, or through a notice-and-takedown system such as the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). We expect companies to disclose their process for responding to these types of requests (F5), as well as data on the number and types of such requests they receive and with which they comply (F7).

See the RDR Index glossary: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#Glossary

Facebook published more accessible data about private requests it received for content or account restrictions (F7). Both Facebook and Google improved their policies for notifying users about content or account restrictions: Facebook committed to notify users when the content they created is restricted, and committed to notify users when they try to access content that has been restricted due to a government demand; meanwhile, Google committed to notify Gmail users in certain cases when it restricts access to their account (F8).

Telefónica was more clear than any other telecommunications company about how it responds to government requests to remove, filter, or restrict content or accounts (F5-F7). No telecommunications company revealed any data about requests they received to remove or block content in response to requests that come from entities other than governments, despite the fact that in some countries non-governmental entities, such as the Internet Watch Foundation in the UK, refer websites to telecommunications companies for blocking (F7).51 Only three telecommunications companies disclosed any data about government requests for content or account restrictions (F6): AT&T, Telefónica, and Telenor. AT&T and Telenor each disclosed the number of requests to block content received per country, whereas Telefónica disclosed more comprehensive information (such as the number of URLs affected and the subject matter associated with the requests), although not consistently for each country in its report.

Some telecommunications companies are starting to disclose more about their user notification policies, with AT&T, Telenor, and Telefónica all disclosing more than others about whether they notify users about blocking content or restricting user accounts (F8). Telenor disclosed that it notifies users when it restricts their account. Telefónica disclosed that it notifies users who attempt to access restricted content that it has been restricted, and the reason for the restriction, when the authorities require them to do so. AT&T disclosed that it attempts to notify users to the extent permitted by law.

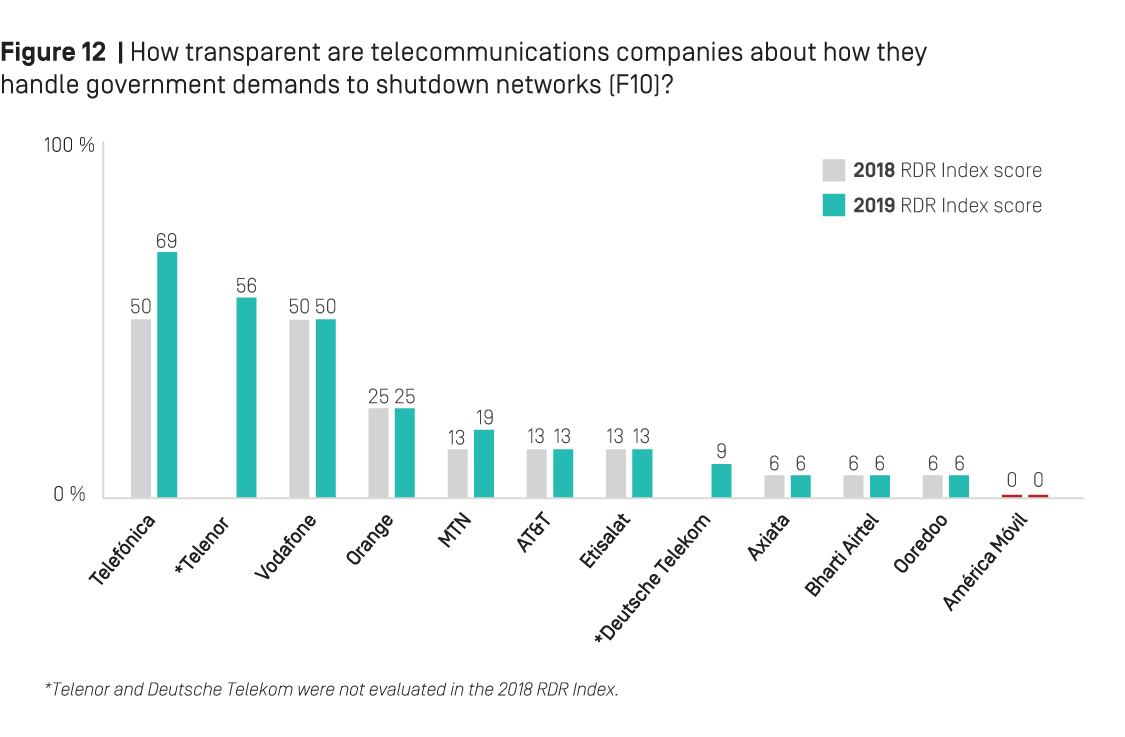

Users of most internet service providers remain in the dark about why network shutdowns happen or who is responsible.

RDR evaluates whether telecommunications companies clearly explain the circumstances under which they may shut down or restrict access to the network or to specific protocols, services, or applications on the network (F10). Only three companies scored 50 percent or higher on this indicator and only two made any improvements since 2018.

Government network shutdown demands

What the RDR Index evaluates: Indicator F10 evaluates how transparent telecommunications companies are about government demands to shut down or restrict access to the network. It assesses if companies disclose the reasons for shutting down service to an area or group of users, if companies clearly explain the process for responding to government network shutdown requests—including if the company commits to push back on such requests—and if companies disclose the number of these types of requests they receive and comply with.

Read the guidance for Indicator F10 of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#F10.

An internet shutdown is defined by experts as the “intentional disruption of internet or electronic communications, rendering them inaccessible or effectively unusable, for a specific population or within a location often to exert control over the flow of information.” According to the Shutdown Tracker Optimization Project run by Access Now, the number of internet shutdowns imposed by governments on internet service providers each year more than doubled between 2016 and 2018.52

Putting aside the substantial negative economic implications, the human rights consequences for populations affected by internet shutdowns have been extensively documented. In 2017, the Freedom Online Coalition—a partnership of 30 governments—issued a formal statement expressing “deep concern over the growing trend of intentional state-sponsored disruptions of access to or dissemination of information online. Measures intended to render internet and mobile network services inaccessible or effectively unusable for a specific population or location, and which stifle exercise of the freedoms of expression, association, and peaceful assembly online undermine the many benefits of the use of the internet and ICTs.”53

Telefónica jumped into first place as the most transparent company about network shutdowns due to improved disclosure of its process for responding to network shutdown demands. It was one of only three companies to disclose any information about the number of shutdown requests it received. It was the only telecommunications company to also disclose the number of requests with which it complied.

Vodafone (unchanged since 2018) and Telenor both disclosed the circumstances under which they may shut down service, and both disclosed a clear commitment to push back on network shutdown demands. Telefónica, Telenor, and Vodafone all clearly disclosed their process for responding to network shutdown demands. Telefónica and Telenor, a new addition to the RDR Index, both disclosed the number of shutdown demands they received per country. They also both listed the legal authorities or legal frameworks that can issue shutdown demands or establish the basis for doing so (although they did not list the number of demands per type of authority).

MTN of South Africa was the only other company previously included in the RDR Index to improve its transparency about network shutdowns. It made slight improvements to its disclosure of the reasons why it may shut down its networks, and its process for responding to government shutdown demands.

América Móvil remained the only telecommunications company in the RDR Index to fail to disclose any information about network shutdowns.

Only two companies committed to uphold network neutrality principles and many disclosed little or nothing about their network management policies.

RDR also measures whether telecommunications companies clearly disclose that they do not prioritize, block, or delay certain types of traffic, applications, protocols, or content for any reason beyond assuring quality of service and reliability of the network (F9).

Disclosure of network management policies

What the RDR Index evaluates: Indicator F9 assesses how transparent telecommunications companies are about their network management policies and practices. It evaluates if companies publicly commit to upholding net neutrality principles by clearly disclosing that they do not prioritize, block, or delay certain types of traffic, applications, protocols, or content for any reason beyond assuring quality of service and network reliability. Companies that offer “zero rating” programs or similar sponsored data programs—or engage in any other types of practices that prioritize or shape network traffic that undermine net neutrality—should not only clearly disclose these practices but should also explain why.

Read the guidance for Indicator F9 of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#F9.

Telefónica and Vodafone distinguished themselves as the most transparent among all telecommunications companies about their network management policies. They were the only two companies in the RDR Index to disclose they do not prioritize, block, or delay certain types of traffic, applications, protocols, or content for any reason beyond assuring quality of service and reliability of the network.

Five telecommunications companies did not disclose any information about their network management practices: Deutsche Telekom, Etisalat, MTN, Ooredoo, and Orange.

In April 2019—less than a month after the massacre of 50 worshippers at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand by an Australian white nationalist gunman—the Australian government passed a law imposing steep fines and criminal sentences for company employees if “abhorrent violent material” is not removed “expeditiously.” Australian media companies and human rights groups vigorously opposed the law, warning that it would lead to censorship of journalism and activism. Yet it was passed without meaningful public consultation or any form of impact assessment.54

It has long been standard practice of authoritarian governments to hold internet services and platforms strictly liable for users’ speech, with government authorities defining terrorism and disinformation so broadly that companies are forced to proactively censor speech that should be protected under human rights law.55 Faced with problems of terrorist incitement and deadly hate speech propagated through internet platforms and services, a number of democracies are also moving to increase the legal liability of companies that fail to delete content transmitted or published by users. The box below lists recent laws affecting freedom of expression in home markets of many companies included in the RDR Index.

Regulations affecting freedom of expression proposed or enacted since 2018

The following is a (non-exhaustive) list of proposed or enacted legislation in 2018 and 2019 in regions or countries where the companies we evaluate are headquartered.

The European Union: In April 2019, the European Parliament approved the Regulation on Tackling the Dissemination of Terrorist Content Online, requiring platforms to remove certain content within an hour of notification or face fines of up to 4 percent of a company’s annual global turnover.56 The regulation will be further negotiated before being finalized. The EU passed the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market, which was heavily contested by digital rights activists for including measures critics say could undermine freedom of expression and lead to over censoring content.57

France: In December 2018, France enacted a new misinformation law.58 Designed to impose strict rules on the media during the three months preceding any election, the law targets “fake news” that seeks to influence electoral outcomes. The law includes a “duty of cooperation” for online platforms.

Germany: In January 2018, the Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG) went into effect.59 It targets the dissemination of hate speech and other illegal content online by requiring social networks to remove content within 7 days—and in some cases within just 24 hours—or face hefty fines.

The United Kingdom: In April 2019, the UK government published an Online Harms White Paper which proposes making internet companies responsible for illegal, harmful, or disreputable content on their platforms and introducing a new regulator with enforcement authority.60 It includes a proposal that company executives be held personally liable for harmful content appearing on their platforms.

China: In November 2018, China released the Regulation on Security Assessment of Internet Information Services Having Public-Opinion Attributes or Social Mobilization Capabilities.61 It obliges companies to monitor—and in some instances block—signs of activism or opinions deemed threatening by the government.

India: In December 2018, India published the Information Technology [Intermediary Guidelines (Amendment) Rules].62 Under the draft rules, officials could demand social media companies to remove certain posts or videos. Though the rules clarify that requests must be issued through a government or court order they also require service providers to proactively filter unlawful content. Critics say the types of content that service providers would be required to prohibit go beyond constitutional limitations on freedom of expression.

Russia: In March 2019, Russia passed two laws that make it a crime for individuals and online media to “disrespect” the state and spread “fake news” online, authorizing the government to block websites, impose fines, and jail repeat offenders.63 In May 2019, Putin signed the controversial “Sovereign Internet” legislation, which will further solidify the government’s control over the internet.

A key human rights concern is that intermediary liability can be abused, particularly when definitions of disinformation, hate speech, and extremism are subject to debate even in some of the world’s oldest democracies.64 Another concern stems from evidence gathered by researchers in countries where strict liability laws are already in force: when in doubt platforms can be expected to over-censor if they face steep fines or other penalties for under-censoring.65 Such “collateral censorship” can silence journalism, advocacy, and political speech when companies’ automated mechanisms—and even human moderators operating under extreme time pressure without sufficient understanding of cultural contexts and local dialects or slang—are often not capable of telling the difference between journalism, activism, satire, or debate on the one hand, and hate speech or extremism on the other.66

Certainly, companies need to be able to recognize and react quickly to urgent life-and-death situations, such as the Christchurch shooting or the Myanmar genocide in 2017, during which hate speech in support of ethnic purges was disseminated via Facebook.67 But given the human rights risks associated with increased intermediary liability for users’ speech and behavior, some legal experts suggest shifting the regulatory focus away from liability and instead require companies to take broader responsibility for their impact on society, and to build businesses committed to treating users fairly and humanely.68

David Kaye, the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, calls on governments to focus on “ensuring company transparency and remediation to enable the public to make choices about how and whether to engage in online forums.”69 Terms of service should be based on human rights standards, developed and constantly improved upon through a process of public consultation, risk assessment, and external review. To guard against abuse of regulations related to online speech, Kaye also emphasizes that judicial authorities—not government agencies—should be the arbiters of what should be considered lawful or illegal expression. Furthermore, governments should release their own data to the public about all demands made of companies to restrict speech or access to services, subject themselves to oversight mechanisms in order to prevent abuse, and ensure that the law imposes appropriate legal penalties upon officials or government entities who abuse their power.

Developing effective capabilities to stop serious harms without inflicting collateral damage on the legitimate rights of others will require greater collaboration between governments, companies, and civil society than has yet occurred. Innovation is needed in technical design, business practices, and government regulatory approaches, in addition to more active engagement with civil society and subject-matter experts as part of the risk assessment and mitigation process. Special attention must be paid to politically sensitive regions, ethnic conflicts, and civil wars in addition to elections.

A clear first step is not merely to encourage, but to require companies to improve their governance, oversight, and due diligence to mitigate and prevent their products, platforms, and services from corroding human rights of users and the communities in which they live. As discussed in Chapter 3, regulations requiring strong corporate governance and oversight of human rights risks are badly underdeveloped.

Secondly, companies committed to respecting freedom of expression must maximize transparency about all the ways that content and information flows are being restricted or otherwise manipulated on their platforms and services. This is especially vital at a time when government demands, mechanisms, and regulatory frameworks are evolving rapidly and unpredictably in scope and scale around the world.

As the 2019 RDR Index results clearly show, companies have not come close to the maximum degree of transparency about all the ways that freedom of expression can be constrained via their platforms and services. In the current regulatory climate, greater transparency could hardly be more urgent.

1. Commit to robust governance: Board-level oversight, risk assessment, stakeholder engagement, and strong grievance and remedy mechanisms are all essential for mitigating risks and harms before the problems become so severe that governments are compelled to step in and regulate. (See also the governance recommendations in Chapter 3.)

2. Maximize transparency: Companies should publish regular transparency reports covering actions taken in response to external requests as well as proactive terms of service enforcement. Such reports should include data about the volume and nature of content that is restricted, blocked, or removed, or information about network shutdowns, as well as the number of requests that were made by different types of government or private entities.

3. Provide meaningful notice: In keeping with the Santa Clara Principles for content moderation and terms of service enforcement (santaclaraprinciples.org), companies should give notice to every user whose content is taken down or account suspended, explain the rationale or authority for the action, and provide meaningful opportunity for timely appeal. (See also the remedy recommendation in Chapter 3.)

4. Monitor and report on effectiveness of content-related processes: Companies should monitor and publicly report on the quantitative and qualitative impact of their compliance with content removal regulations, in order to help the public and government authorities understand whether existing regulations are successful in achieving their stated public interest purpose. Conduct and publish assessments on the accuracy and impact of removal decisions made by the company when enforcing its terms of service, as well as actions taken in response to regulations or official requests made by authorities, including data about the number of cases that had to be corrected or reversed in response to user grievances or appeals.

5. Engage with stakeholders: Maximize engagement with individuals and communities at greatest risk of censorship and who are historically known to have been targets of persecution in their societies, as well as those most at risk of harm from hate speech and other malicious speech. Work with them to develop terms of service and enforcement mechanisms that maximize the protection and respect of all users’ rights.

1. Require strong corporate governance and oversight: Specifically, require companies to publish information about their human rights risks, including those related to freedom of expression and privacy, implement proactive and comprehensive impact assessments, and establish effective grievance and remedy mechanisms. (See also the recommendations for governments in Chapter 3.)

2. Require corporate transparency: Companies should be required to include information about policies for policing speech, as well as data about the volume and nature of content that is restricted or removed, or accounts deactivated for any reason.

3. Be transparent: Governments should publish accessible information and relevant data about all requirements and demands made by government entities (national, regional, and local) that result in the restriction of speech, access to information, or access to service. For governments that are members of the Open Government Partnership—an organization dedicated to making governments more open, accountable, and responsive to citizens—transparency about requests and demands made to companies affecting freedom of expression should be considered a fundamental part of that commitment.

4. Assess human rights impact of laws: While requiring companies to conduct assessments, governments should also be required by law to conduct human rights impact assessments on proposed regulation of online speech. Any liability imposed on companies for third-party content should be consistent with international human rights instruments and other international frameworks, as outlined by the Manila Principles on Intermediary Liability (manilaprinciples.org).

5. Ensure adequate recourse: Governments should ensure that individuals have a clear right to legal recourse when their freedom of expression rights are violated by any government authority, corporate entity, or company complying with a government demand.

6. Ensure effective and independent oversight. Any government bodies empowered to flag content for removal by companies, or empowered to require the blockage of services, or to compel network shutdowns, must be subject to robust, independent oversight and accountability mechanisms to ensure that government power to compel companies to restrict online speech, suspend accounts, or shut down networks is not abused in a manner that violates human rights.

7. Collaborate globally: Governments that are committed to protecting freedom of expression online should work proactively and collaboratively with one another, as well as with civil society and the private sector, to establish a positive roadmap for addressing online harms without causing collateral infringement of human rights.

[46] Ghosh, Dipayan and Ben Scott, “Digital Deceit: The Technologies Behind Precision Propaganda on the Internet,” New America Public Interest Technology, January 23, 2018, www.newamerica.org/public-interest-technology/policy-papers/digitaldeceit/ and Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (PublicAffairs, 2019), www.publicaffairsbooks.com/titles/shoshana-zuboff/the-age-of-surveillance-capitalism/9781478947271

[47] Vishal Manve, “Twitter Tells Kashmiri Journalists and Activists That They Will Be Censored at Indian Government's Request,” Global Voices, September 14, 2017, advox.globalvoices.org/2017/09/14/kashmiri-journalists-and-activists-face-twitter-censorship-at-indian-governments-request/ and “Germany: Flawed Social Media Law,” Human Rights Watch, February 14, 2018, www.hrw.org/news/2018/02/14/germany-flawed-social-media-law

[48] Rebecca MacKinnon et al, “Fostering Freedom Online: The Role of Internet Intermediaries” (UNESCO, 2014), www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/resources/publications-and-communication-materials/publications/full-list/fostering-freedom-online-the-role-of-internet-intermediaries/

[49] “Removal requests,” Twitter Transparency Report, transparency.twitter.com/en/removal-requests.html

[50] “Government requests to remove content,” Google Transparency Report, transparencyreport.google.com/government-removals/overview?hl=en

[51] Jim Killock, “UK Internet Regulation – Part I: Internet Censorship in the UK today” (Open Rights Group, December 18, 2018), www.openrightsgroup.org/about/reports/uk-internet-regulation

[52] “Keep It On,” Access Now, accessed April 22, 2019, www.accessnow.org/keepiton

[53] “The Freedom Online Coalition Joint Statement on State Sponsored Network Disruptions” (Freedom Online Coalition, 2017), www.freedomonlinecoalition.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/FOCJointStatementonStateSponsoredNetworkDisruptions.docx.pdf

[54] Damien Cave, “Australia Passes Law to Punish Social Media Companies for Violent Posts,” The New York Times, April 3, 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/04/03/world/australia/social-media-law.html

[55] Leonid Bershidsky, “Disrespect Putin and You'll Pay a $23,000 Fine, “ Bloomberg, March 14, 2019, www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-03-14/russian-censorship-laws and James Griffiths, “China's censors face a major test in 2019. But they've spent three decades getting ready,” CNN, January 7, 2019, www.cnn.com/2019/01/04/asia/china-internet-censorship-2019-intl/index.html

[56] “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Preventing the Dissemination of Terrorist Content Online” (European Commission, September 12, 2018), ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/soteu2018-preventing-terrorist-content-online-regulation-640_en.pdf

[57] “Directive (EU) 2019/… of the European Parliament and of the Council on Copyright and Related Rights in the Digital Single Market and Amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC” (European Parliament, March 26, 2019, www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P8-TA-2019-0231+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN#BKMD-16

[58] “Proposition de Loi Relative À La Lutte Contre La Manipulation de L’information” (Assemblėe Nationale, November 20, 2018), www.assemblee-nationale.fr/15/ta/tap0190.pdf; Also see Alexander Damiano Ricci, “French opposition parties are taking Macron’s anti-misinformation law to court,” Poynter, December 4, 2018, www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2018/french-opposition-parties-are-taking-macrons-anti-misinformation-law-to-court

[59] “Act to Improve Enforcement of the Law in Social Networks (Network Enforcement Act)” (Bundestag, June 12, 2018), www.bmjv.de/SharedDocs/Gesetzgebungsverfahren/Dokumente/NetzDG_engl.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

[60] “Online Harms White Paper” (Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport et al, April 8, 2019), www.gov.uk/government/consultations/online-harms-white-paper

[61] “Regulation on Security Assessment of Internet Information Services Having Public-Opinion Attributes or Social Mobilization Capabilities” (Cyberspace Administration of China, November 15, 2018), www.cac.gov.cn/2018-11/15/c_1123716072.htm

[62] “The Information Technology [Intermediaries Guidelines (Amendment) Rules]” (Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, December 24, 2018), meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/Draft_Intermediary_Amendment_24122018.pdf

[63]“Bill No. 608767-7: On Amendments to the Federal Law "On Communications" and the Federal Law "On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection"” (State Duma Committee on Information Policy, Information Technologies and Communications, April 22, 2019, sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/608767-7?fbclid=IwAR2LHSnuRHxrEmP7o0OyVVJzhuKySbNNUXmLgJuOFbesKbN

[64] Rebecca MacKinnon et al, “Fostering Freedom Online: The Role of Internet Intermediaries” (UNESCO, 2014), www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/resources/publications-and-communication-materials/publications/full-list/fostering-freedom-online-the-role-of-internet-intermediaries/ and “A Human Rights Approach to Platform Content Regulation,” Freedex, April 2018, freedex.org/a-human-rights-approach-to-platform-content-regulation

[65] Rebecca MacKinnon et al, ”Fostering Freedom Online: The Role of Internet Intermediaries” (UNESCO, 2014).

[66] See for example: Thant Sin, “Facebook Bans Racist Word ‘Kalar’ In Myanmar, Triggers Collateral Censorship,” Global Voices Advox, June 2, 2017, advox.globalvoices.org/2017/06/02/facebook-bans-racist-word-kalar-in-myanmar-triggers-collateral-censorship/ and The DiDi Delgado, “Mark Zuckerberg Hates Black People,” Medium, May 18, 2017, medium.com/@thedididelgado/mark-zuckerberg-hates-black-people-ae65426e3d2a

[67] Hogan, Libby and Michael Safi, “Revealed: Facebook hate speech exploded in Myanmar during Rohingya crisis,” The Guardian, April 3, 2018, www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/03/revealed-facebook-hate-speech-exploded-in-myanmar-during-rohingya-crisis

[68]Tarleton Gillespie, “How Social Networks Set the Limits of What We Can Say Online,” WIRED, June 26, 2018, www.wired.com/story/how-social-networks-set-the-limits-of-what-we-can-say-online

[69]“A Human Rights Approach to Platform Content Regulation,” Freedex, April 2018, freedex.org/a-human-rights-approach-to-platform-content-regulation/