Data privacy has become a key issue over the past several years, with both lawmakers and the public crying foul over the lack of accountability and transparency by companies about how they handle user data.

As news about privacy breaches and deceptive practices involving major U.S.-based companies continued to dominate headlines over the past year, tough new data protection regulations came into force in Europe and in a number of countries around the world. Regulatory efforts and debates in the U.S. gained new urgency, as it became clear that the U.S. cannot afford to remain so far out of step with major global trends on privacy regulation. The state of California—unwilling to wait for national action—passed its own privacy law. Even companies that had previously lobbied against comprehensive national privacy regulation in the U.S. have embraced the inevitable and expressed support for regulation, hoping to be able to influence its final shape.

For a discussion of regulatory trends and gaps, see section 5.6.

Nearly all ranked companies made some improvements to their disclosures of policies and practices related to privacy in the past year. However, companies that led the Privacy category of the 2019 RDR Index distinguished themselves by going beyond minimum legal requirements—at least in certain areas, even if they were deficient in others. This demonstrates that current data protection regulations alone may not be sufficient to hold companies accountable for the broader spectrum of policies affecting users’ privacy. Regulations also need to address issues like data security as well as how companies allow third parties, like advertisers or governments, access to user data. Results from this year’s Index show that while many companies made concrete improvements in areas that appear to be largely driven by regulatory demands, there remains ample room for improvement.

Most companies still do not disclose enough about policies and practices affecting users’ privacy.

How much do we really know about what data companies collect, hold, and share—with other companies, with advertisers, or with government authorities including law enforcement? How much control do people really have over what is collected and shared about them, and with whom? How much do we know about what companies are doing to keep our data secure?

As in previous years, the answer to these questions is: not enough. Despite some positive steps forward, results from the 2019 RDR Index show that most of the 24 companies evaluated failed to meet minimum standards of transparency about how they handle and secure users’ data.

How transparent are companies about policies and practices affecting privacy?

What the RDR Index evaluates: The RDR Index evaluates company disclosure of policies and practices affecting privacy across 18 indicators that collectively address how transparent companies are about what they do with user information, with whom they share it, and what they do to secure it.70 Indicators assess:

- Accessibility and clarity of privacy policies: How clear and accessible companies make their privacy policies, and if and how they notify users when they make changes to these terms (P1, P2).

- User information: How transparent companies are about how they collect, share, and handle user information (P3-P9).

- Government demands: How companies handle government and other types of third-party requests for user information (P10, P11, P12).

- Security: If companies have clear processes and safeguards in place for keeping user information secure (P13-P18).

To review the privacy indicators of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#P

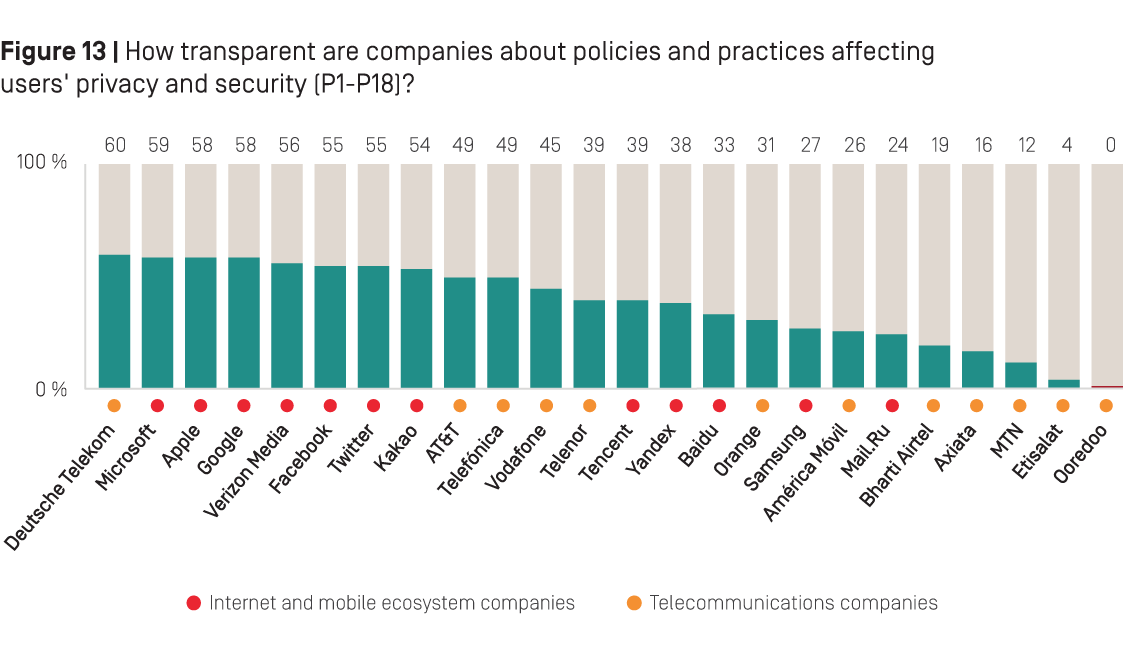

While nearly all companies in the 2019 RDR Index made some improvements over the last year, no company scored higher than 60 percent in the Privacy category—and most earned a score of just 50 percent or lower (see Figure 13 below). This means no company in the RDR Index disclosed enough about their policies and practices for their users to fully understand the full range of privacy and security risks they face when using their services.

As Figure 13 above shows, German telecommunications company Deutsche Telekom earned the highest average privacy score of all companies—including internet and mobile ecosystem companies. This is the first time since publishing our inaugural ranking in 2015 that a telecommunications company topped the Privacy category.71 The company’s high score on privacy-related policies and disclosures was due to its stronger disclosure of its handling of user data, and of its security policies, relative to its peers.

Telecommunications companies across the board disclosed little or nothing about their relationships with governments—how they handle demands by government entities or law enforcement to hand over user data. In many cases this gap in disclosure explains their low scores in the Privacy category in relation to internet and mobile ecosystem companies. Apart from Deutsche Telekom, most telecommunications companies also did not disclose enough about how they handle user information, and were particularly opaque about their data retention policies and practices. Notably, two telecommunications companies—Qatar-based Ooredoo and UAE-based Etisalat—failed to publish privacy policies at all.

Among internet and mobile ecosystem companies, Microsoft earned the highest average score in the Privacy category for its stronger disclosure of its handling of government requests for user information, and of its security policies. The company made notable improvements to its disclosure of its data breach policies (P15), and rolled out an end-to-end encryption option for both Outlook and Skype (P16).

Apple and Google tied for the second-best score on privacy-related disclosures among internet and mobile ecosystem companies, after Microsoft. Apple disclosed more about its security policies than any other internet and mobile ecosystem company, and stood out for having the strongest disclosure of encryption policies and practices of all of its peers. Google’s high score was due to stronger disclosure of how it handles government requests for user information. Apart from Twitter, it also disclosed more about how it handles user information than all other internet and mobile ecosystem companies evaluated—although there is ample room for improvement.

Although Facebook and Twitter made key improvements, both companies earned a score of just 55 percent, tying for fifth in the Privacy category among internet and mobile ecosystem companies. Twitter disclosed more than all other internet and mobile ecosystem companies about its handling of user information, but received one of the lowest scores among its peers on indicators evaluating disclosure of security policies (P13-P18); the company failed to reveal anything at all about what policies it has in place to respond to data breaches (P15).

Facebook made notable improvements to its disclosure about how it handles user information, but still did not give users a clear picture of what it does with user data, nor did it provide users with clear options to control what data is shared. The company also disclosed insufficient information about its security policies, including safeguards around employee access to user data and its policies for handling data breaches.

Chinese internet companies Baidu and Tencent also made significant improvements to their privacy and security disclosures, which may be a result of new directives that came into effect in May 2018 requiring companies to be more transparent about different aspects of how they handle personal data.72

New data protection regulations in the EU and elsewhere seem to be pushing companies in the right direction—but critical gaps need to be addressed if companies are to be fully accountable about how personal data is handled.

Nearly every company evaluated in this year’s RDR Index updated their privacy policies in 2018, as new data protection regulations came into effect in the EU as well as in several countries around the world. But what does this mean for users? Do people know more about what their mobile phone service or internet platform is doing with their data than they did a year ago? Do people have more control over what data about them is being collected and shared, and with whom? (For more about data protection regulations that same into force in 2018, see section 5.6.)

How transparent are companies about their handling of user information?

What the RDR Index evaluates: The RDR Index has seven indicators evaluating how transparent companies are about how they handle user information.73 We expect companies to disclose: each type of user information they collect (P3); each type of user information they share, including the types and names of the third parties with whom they share it (P4); the purpose for collecting and sharing user information (P5); and their data retention policies, as well as time frames for storage and deletion (P6).

Companies should also disclose options users have to control what information is collected and shared, including for the purposes of targeted advertising (P7), and should clearly disclose if and how they track people across the internet using cookies, widgets, or other tracking tools embedded on third-party websites (P9). We also expect companies to clearly disclose if and how users can obtain all public-facing and internal data companies hold about users, including metadata (P8).

User information: RDR defines “user information” as any data that is connected to an identifiable person, or may be connected to such a person by combining datasets or utilizing data-mining techniques. User information is any data that documents a user’s characteristics and or activities—which may or may not be tied to a specific user account—and includes, but is not limited to, personal correspondence, user-generated content, account preferences and settings, log and access data, data about a user’s activities or preferences collected from third parties either through behavioral tracking or purchasing of data, and all forms of metadata.

See the privacy indicators of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#P

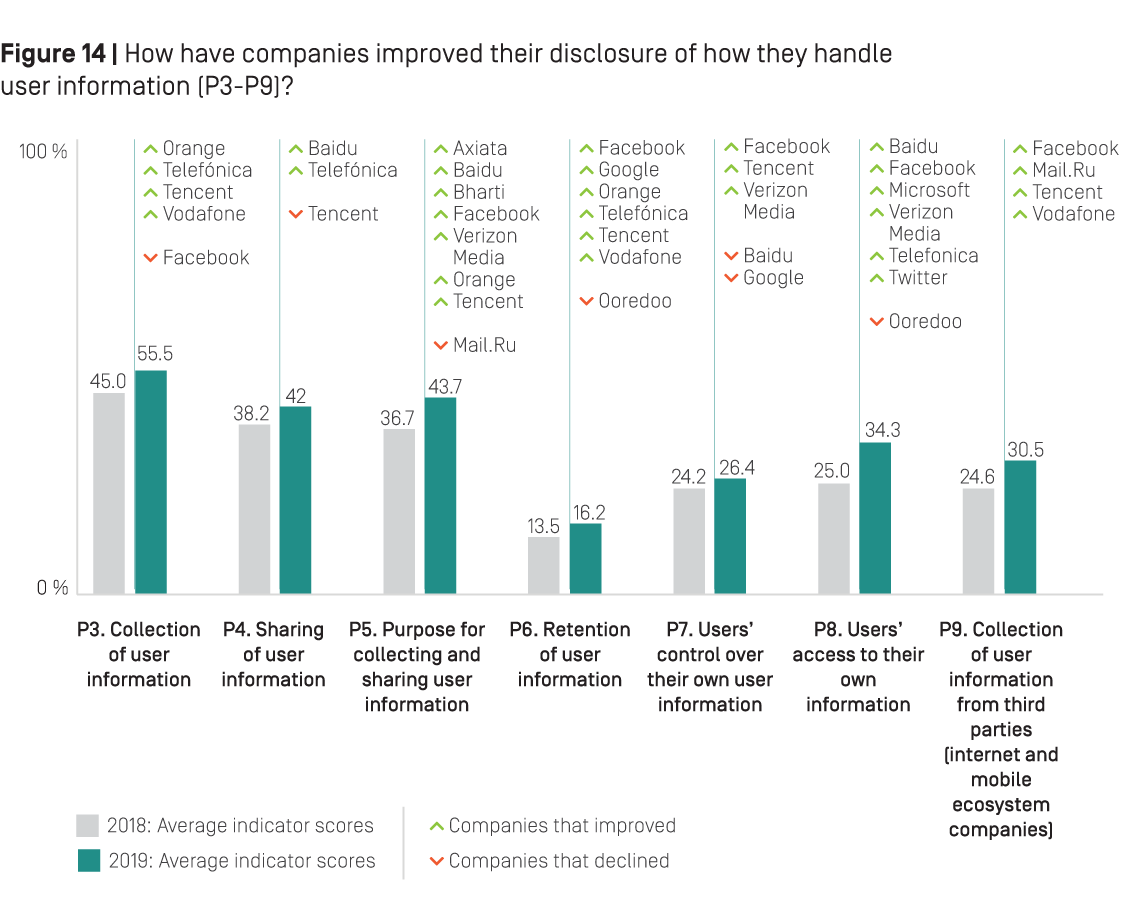

Results were mixed. Figure 14 below shows improvements and declines by companies across all indicators evaluating disclosure of how they handle user information. A majority of companies—13 of the 22 companies evaluated in the 2018 RDR Index—made some improvements by clarifying different aspects of how they handle user information. But there were also key areas where companies made little progress—or in some cases, disclosed even less about their handling of user data than they had previously.

Notable trends include:

Improved clarity about reasons for collecting and sharing user data (P5). Seven companies—Axiata, Baidu, Bharti Airtel, Facebook, Orange, Tencent, and Verizon Media—improved their transparency about why they collect and share user data although, on average, the scores for this indicator remained low. Notably, the Chinese internet company Baidu earned the highest score on this indicator due to its improved disclosure about its purpose for sharing user information, and for clearly committing to limit its use of data to the purpose for which it was collected. But the Russian internet company Mail.Ru lost points on this indicator: its revised privacy policy for the social network VKontakte no longer mentioned a commitment to limit its use of data to the purpose for which it was collected, which was disclosed in the previous version, evaluated for the 2018 RDR Index.

Improved options for users to obtain their data (P8). Six companies—Baidu, Facebook, Microsoft, Telefónica, Twitter, and Verizon Media—clarified how people can obtain the data that these companies hold about them. Facebook this year earned the highest score on this indicator, after clarifying options users have to obtain their data for all of Facebook’s services, including the Facebook social network service, WhatsApp, and Instagram.

Improved clarity about data retention (P6). Six companies—Facebook, Google, Orange, Telefónica, Tencent, and Vodafone—improved their disclosure of their data retention policies. However, most companies were the least transparent about these policies than any other aspect of they handle user information.

Improved clarity of what data is collected (P3). Four companies—Orange, Telefónica, Tencent, and Vodafone—improved their disclosure of what types of data they collect. Tencent disclosed more than any other company in the RDR Index about what types of data it collects and how it collects it. Facebook lost points on this indicator for disclosing less clear information about how Instagram collects user information.

Despite improvements, companies still don’t give users enough control over what data is collected and shared.

Indicator P7 evaluates if companies give users clear options to control what information is collected and shared about them, including for the purposes of targeted advertising.74 We expect companies to clearly disclose options for users to control what information is collected about them, and to delete specific types of information without requiring users to delete their entire account. We also expect companies to give users options to control how their information is used for advertising and to disclose that targeted advertising is off by default.

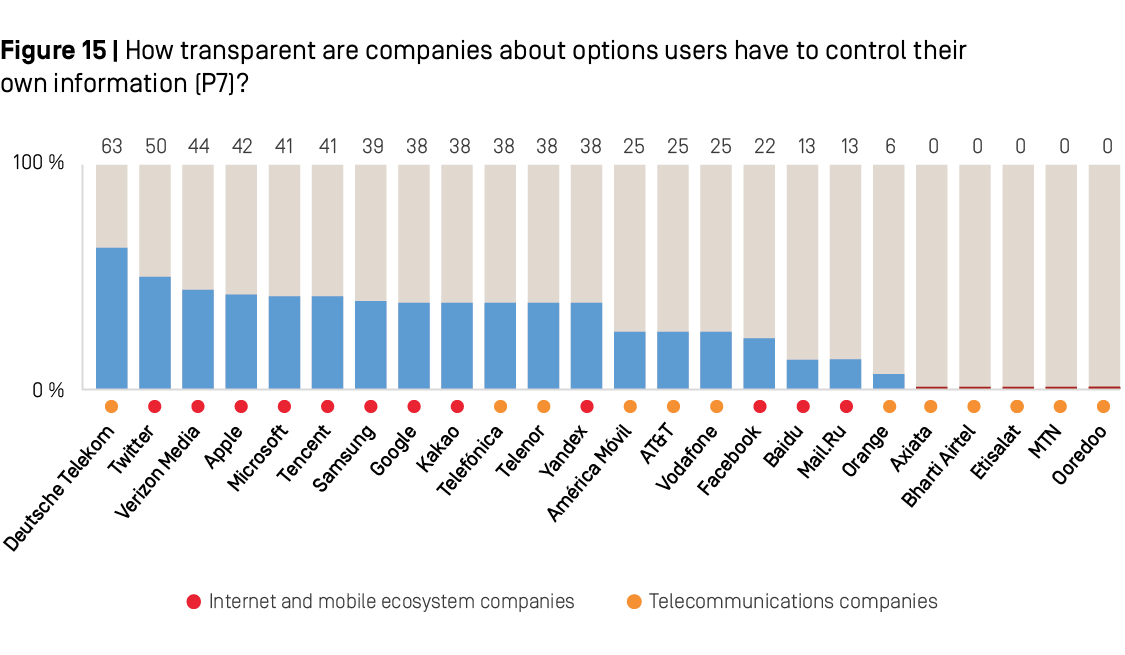

The 2018 RDR Index showed that most companies gave unclear options for users to control what is collected and shared about them, and how that data is used for the purposes of targeted advertising.75 Results of the 2019 RDR Index show that companies made little progress in this area. Just three companies—Facebook, Tencent, and Verizon Media—improved their disclosure of options users have to control what information is collected and shared about them.

Deutsche Telekom was the most transparent of all companies about giving users options to control what information is collected and shared about them, including for the purposes of targeted advertising. In addition to disclosing user options to control what information is collected, and to delete some of this data, Deutsche Telekom was the only company evaluated in the RDR Index to disclose that targeted advertising is off by default: users must opt-in in order for their data to be used for this purpose—and they can revoke their consent at any time.

Yet the other European telecommunications companies in the RDR Index—Orange, Telefónica, Telenor, and Vodafone—disclosed notably little about what options people have to control how companies use their data. Orange disclosed far less than its peers: it lacked clarity about what options users have to control what types of data it collects. Nor did it clearly specify what types of data can be deleted. It also disclosed very limited options for users to control if and how their data is used for the purposes of targeted advertising and did not indicate if targeted advertising was off by default.

Among internet and mobile ecosystem companies, Twitter disclosed more than any of its peers about options users have to control what data is collected and shared. It was one of the few companies to disclose options for users to control how their data is used for targeted advertising.

Google lost points on this indicator this year after revising its disclosure about whether Android users can turn off their location data. The company previously stated that Android users could control whether the company collected location data through a setting at the device level. However, Google’s revised policy on managing location history stated that some location data may still be collected even when location history is turned off.

Facebook disclosed slightly more than in the previous year about ways users can control their information—it provided two examples of types of data that users can delete—but it remained one of the lowest-scoring companies on this indicator (although up from having the very lowest score on this indicator in the 2018 RDR Index).

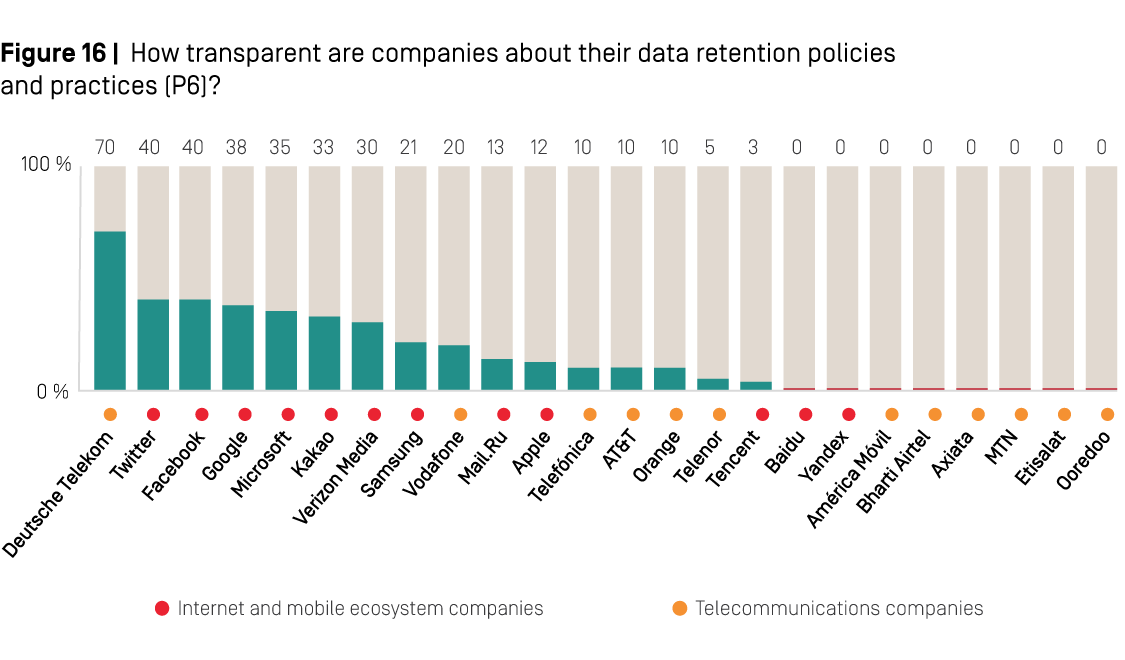

Few companies disclosed enough about their data retention policies for users to give informed consent about what companies are doing with their data.

Indicator P6 evaluates how transparent companies are about their data retention policies. The RDR Index expects each company to clearly disclose how long they retain each type of user data they collect, including what de-identified data they retain—as well as its process for de-identifying that data—and its time frames for deleting user data after a user’s account is terminated.

RDR defines “de-identified” user information as data that companies collect and retain but only after removing or obscuring any identifiable information from it. This includes explicit identifiers like names, email addresses, and any government-issued ID numbers, as well as identifiers like IP addresses, cookies, and unique device numbers.

See the RDR Index glossary of terms at: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#Glossary

As with other indicators in the RDR Index evaluating disclosure of data handling policies, Deutsche Telekom earned the top score on Indicator P6, disclosing more about its data retention policies than any other company evaluated. The company provided time frames for retaining some types of user data it collects, and revealed more about what de-identified user data it retains than any of its peers.

As Figure 16 above shows, half of the 12 telecommunications companies evaluated in the 2019 RDR Index received no points on Indicator P6 because they provided no information about any aspect of their data retention policies evaluated in this indicator. Among European telecommunications companies, Telefónica, Telenor, and Vodafone each disclosed some information about how long they retain user data, but revealed nothing further about policies for de-identifying user information, or if they delete all user information after the account is terminated. Notably, although Orange improved its disclosure by providing a time frame for deleting some types of data after users terminate their account, it still earned one of the lowest scores among telecommunications companies on this indicator.

Among internet and mobile ecosystem companies, Twitter tied with Facebook for the top score on this indicator (P6)—although a high score of just 40 percent on this indicator reflects how little companies disclosed about their data retention policies. Twitter revealed how long it retains some of the user information it collects, and disclosed what de-identified data it retains, and its process for de-identifying some of that data. Facebook earned a score improvement by providing examples of retention periods for certain types of user information for Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger, and by committing to delete some types of user information after users terminate their Instagram accounts.

Notably, Apple was among the least transparent internet and mobile ecosystem companies, apart from Chinese companies Tencent and Baidu, about its data retention policies. It received a small amount of credit on this indicator for disclosing that it retains location data in a de-identified format, but did not disclose if it does so for other personally identifying data, like IP addresses. It also disclosed nothing about time frames for storing any of the data it collects or when it deletes data after users terminate their accounts.

No company disclosed enough about how they handle government demands to hand over user data, which could expose users to a range of unknown privacy and security risks.

As people depend more on internet and mobile technologies to carry out their daily activities, the data that companies collect about us—tracking our movements, our communications, our web searches, and more—has become a key target for governments and law enforcement. Companies are often caught in the middle between keeping users’ information secure and private, and complying with government demands. Their choices can have dire consequences—particularly when complying with requests from authoritarian regimes where rule of law is weak.

In addition, the rise in anti-terrorism laws around the world—in democratic and authoritarian countries alike—have put increasing pressure on internet and telecommunications companies to provide authorities with access to user data. In its latest Freedom on the Net report, Freedom House documented a substantial increase in laws around the world related to government surveillance in the past two years alone: “Governments in 18 out of 65 countries have passed new laws or directives to increase state surveillance since June 2017, often eschewing independent oversight and exposing individuals to persecution or other dangers in order to gain unfettered access.”76 These laws can include requirements for companies to store data locally and for longer periods of time, lowered legal barriers for authorities to demand that companies hand over data, or regulations aimed at circumventing encryption, all of which can increase the likelihood that a user’s sensitive information ends up in the hands of the government.

In an era of pervasive state surveillance, companies need to be fully transparent about their relationships with governments, including with law enforcement, so that people can make informed choices about if and how to use a particular company’s platform or service. Companies should disclose how they handle government demands to hand over user data—and commit to push back on overly broad demands and demands that are not consistent with governing legal frameworks—and publish data about the number and type of requests for user data they receive and comply with. They should also be clear about whether they inform users when their data has been requested by law enforcement—or cite the legal reason prohibiting them from doing so.

What does RDR mean by “government demands”?

Companies receive a growing number of requests from governments to turn over user information. These requests can come from government ministries or agencies (including from foreign jurisdictions), law enforcement, and court orders in criminal and civil cases, and include requests for real-time access and stored information.

What the RDR Index evaluates: We expect companies to publicly disclose their process for responding to each type of government request they receive—whether through courts, law enforcement, or foreign jurisdictions—along with the basis for complying with these demands. Companies should also publicly commit to pushing back on inappropriate or overbroad requests, to notify users of requests for their information to the extent legally possible, and to disclose the types of cases in which they would be legally prohibited from providing notification. We also expect companies to regularly publish data about the number of government requests they have received and with which they have complied, including the type of government authority that issued the request, whether the demand sought communications content or non-content or both, and whether there are some types of requests about which it is legally prohibited from disclosing specific data.

See the privacy indicators of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#P

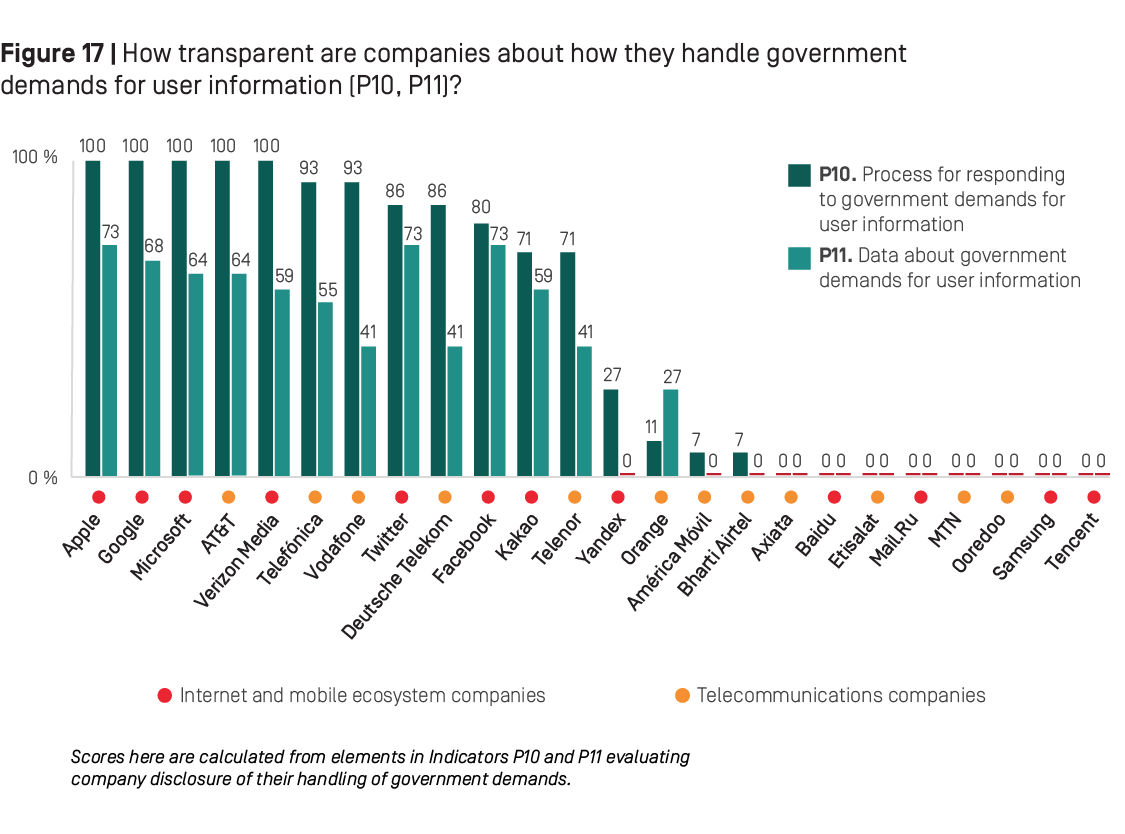

As in previous years, results from the 2019 RDR Index show that internet and mobile ecosystem companies disclosed more than telecommunications companies about their processes for handling government demands, and published more data about their compliance with these requests (see Figure 17 below).

Notably, a handful of U.S.-based companies—Apple, Google, Microsoft, Verizon Media, and AT&T—all earned full credit for comprehensive disclosure of their processes for handling government requests, including those from foreign jurisdictions, and for publishing a clear commitment to push back on overly broad requests (P10). But these companies were less transparent about the actions they took as a result of these demands (P11), due at least in part to legal restrictions: U.S. law prohibits companies from disclosing exact numbers of government requests received for stored and real-time user information under Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) requests or National Security Letters (NSLs), which prevented U.S. companies from being fully transparent in this area.77 As in the 2018 RDR Index, Verizon Media disclosed less data than all other U.S. internet and mobile ecosystem companies about government demands for user information.

Despite falling short in some other privacy areas, high scores on indicators evaluating transparency of handling government demands explains why U.S. internet and mobile ecosystem companies like Google and Facebook earned higher scores in the Privacy category than most of the European telecommunications companies. The European telecommunications companies evaluated, especially those that are members of the Global Network Initiative (GNI), have over the last few years begun to take concrete steps to improve their transparency around their processes for handling government demands. Telefónica and Vodafone in particular have started to publish more robust and comprehensive reports explaining their processes for handling these types of demands across their global operations. Telefónica improved this year by giving more detailed information about the company’s process for responding to government requests.

While these are positive steps forward, European telecommunications companies still did not disclose enough actual data detailing the number and types of these requests they received and complied with, either in their home markets or across the various markets in which they operate (P11). Orange, notably, was the least transparent of all of its European peers: It revealed the legal basis for complying with the French government’s requests, but gave no information about how it responds to these requests or those submitted by foreign governments to its operating companies in other jurisdictions (P10). It published some data about its compliance with government requests in France but not about its handling of requests in other countries where it operates (P11).

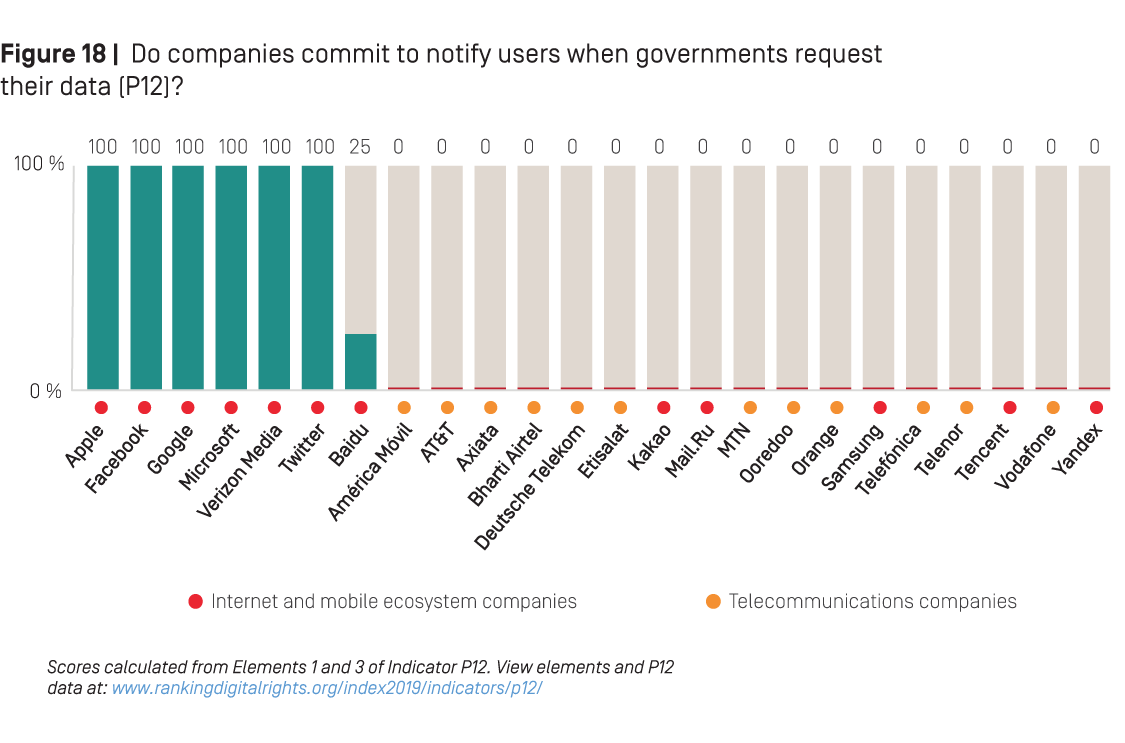

The biggest gap in disclosure between internet and mobile ecosystem companies and telecommunications companies was around user notification policies. Indicator P12 of the RDR Index asks if companies clearly disclose if they notify users when government entities, including courts or other judicial bodies, request their data. It also asks companies to disclose circumstances when they might not notify users, and to explain the types of government requests they are legally prohibited from disclosing.

As Figure 18 above shows, all U.S.-based internet and mobile ecosystem companies—Apple, Google, Microsoft, Verizon Media, Twitter, and Facebook—published a clear commitment to notify users when governmental entities request their data, and offered clear explanations about when they might not notify them, including the types of government requests they are prohibited by law from disclosing. Notably, Chinese internet company Baidu earned some credit on this indicator this year for disclosing that it may hand over user data to officials or courts without notifying users in cases of national security or criminal proceedings.

However, no telecommunications company in the entire RDR Index scored any points on this indicator (P12)—meaning that not one of the 12 telecommunications companies evaluated by the RDR Index publicly committed to notifying users when governments request their data, nor did any of these companies provide a legal reason for not doing so. This means that people who use the internet and mobile phone services provided by these companies have no idea if governments or law enforcement are surveilling or otherwise accessing their communications, whether lawfully or not.

Despite some improvements, most companies do not disclose enough about their security policies for users to be able to make informed choices.

Data security is central to people’s privacy. Security breaches can expose personal and financial information, which comes with a range of short- and long-term privacy risks. But for members of vulnerable communities—including journalists, activists, and members of minority groups—data security can also have physical safety implications. It is incumbent on companies to ensure that the user data they collect and share is strictly secured and, when compromised, to swiftly inform users.

The RDR Index has six indicators evaluating company disclosure of security policies and practices (P13-P18). We do not expect companies to divulge a level of detail about their security procedures that could compromise their security systems or expose them to attack. But we do expect companies to disclose basic information affirming that they follow industry best practices around security so that users can understand what the possible risks are and can make informed decisions about if and how to use a company’s services.

How transparent are companies about their policies and practices for keeping user information secure?

What the RDR Index evaluates: The RDR Index contains six indicators evaluating company disclosure about their policies and practices for keeping user data secure. These evaluate:

- Security oversight: The company should clearly disclose information about its institutional processes to ensure the security of its products and services, including limiting unauthorized employee access to user data (P13).

- Security vulnerabilities: The company should address security vulnerabilities when they are discovered (P14).

- Data breaches: The company should publicly disclose information about its processes for responding to data breaches (P15).

- Security risks: The company should publish information to help users defend themselves against cyber risks (P18).

- Encryption (for internet and mobile ecosystem companies): The company should encrypt user communication and private content so users can control who has access to it (P16).

- Account security (for internet and mobile ecosystem companies): The company should help users keep their accounts secure (P17).

See the privacy indicators of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#P

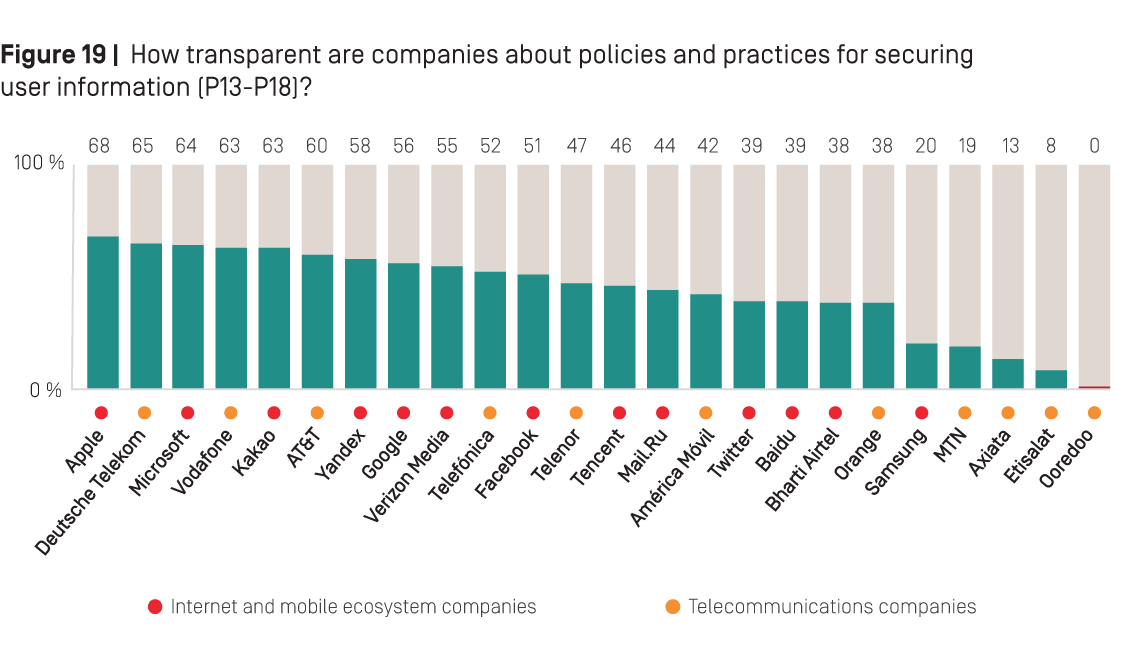

As Figure 19 below shows, Apple received the best average score across the security indicators of any company in the RDR Index. It stood out for its strong encryption policies (P16)—which it improved over the last year. Deutsche Telekom received the highest score among telecommunications companies, and stood out for its strong disclosure of its security oversight systems (P13), and of its data breach policies (P15) relative to many of its peers.

Baidu and Tencent both made notable improvements in a number of areas—although both companies still scored poorly across these indicators overall. Both revealed more information about security oversight policies, including limits on employees’ access to user data (P13), clarified their procedures for responding to data breaches (P15), and revealed that they use encryption for some of their services (P16).

Google was less transparent about its security policies than Apple, Microsoft, Kakao, and Yandex. While it earned the highest score for disclosing ways for users to keep their accounts secure (P17), it failed to disclose anything about its policies for handling data breaches (P15).

Facebook was less transparent than most of its U.S. peers—Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Verizon Media—about its security policies: it revealed little about its policies for limiting employee access to user data (P13), and disclosed nothing about its policies for handling data breaches (P15). But it earned above average marks for its encryption policies (P16): it clearly stated that for WhatsApp, end-to-end encryption is enabled by default, and that Messenger users can enable end-to-end encryption, although it is not enabled by default.

Twitter gave surprisingly little information about its security policies, scoring lower than all U.S. internet and mobile ecosystem companies on these indicators. Like most companies, it failed to disclose any information about how it responds to data breaches (P15). It also did not fully disclose what types of encryption are in place for Twitter (the social network) or Periscope (P16).

Notably, Samsung disclosed less than all internet and mobile ecosystem companies about its security policies. It disclosed nothing about its policies for responding to data breaches (P15), or about what types of encryption are in place to protect user information in transit or on Samsung devices (P16). It also lost points this year for failing to disclose if it made any modifications to the Android mobile operating system and how those changes might impact users’ ability to receive security updates (P14).

Companies are becoming more transparent and accountable about how they handle data breaches—although most in the RDR Index still failed to disclose anything about their policies for addressing these incidents.

Data breaches continue to make headlines, growing both in number and in scope. More than 59,000 data breaches have been reported in Europe since the GDPR became applicable in May 2018.80 In September 2018, hackers gained access to the data of up to 90 million Facebook users.81 Also in 2018, India’s biometric database, Aadhaar, suffered multiple breaches that exposed the personal records of more than 1 billion Indian citizens.82

Data breaches can occur as a result of malicious actors and external threats, as well as from so called “insider threats,” which can be a result of poor internal security oversight.83 However, even with strong security safeguards in place, companies can still experience breaches. And, these incidents not only pose a significant threat to individuals’ financial and personal security—and risk the public’s trust—they also hurt a company’s bottom line: a data breach, on average, costs a company $3.86 million, according to a 2018 study by IBM.84 That study also found that more serious breaches can cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

In response to the growing number of data breaches, the RDR Index in 2017 began evaluating how transparent companies are about their policies for handling these types of incidents. The 2017 RDR Index introduced a new indicator (P15) that evaluates company disclosure of their processes for responding to data breaches and of providing remedy to affected users.

How transparent are companies about their processes for handling data breaches?

What the RDR Index evaluates: Indicator P15 evaluates if a company clearly discloses a commitment to notify the relevant authorities without undue delay when a data breach occurs, if a company clearly discloses its process for notifying data subjects who might be affected by a data breach, and if a company explains what kinds of steps it will take to address the impact of a data breach on its users.

While many jurisdictions legally require companies to notify relevant authorities or take certain steps to mitigate the damage of data breaches, companies may not necessarily be legally compelled to disclose this information to the public or affected individuals. Even if there is a legal requirement to notify affected individuals, the exact definition of “affected individuals” can also vary significantly in different jurisdictions. However, regardless of whether the law is clear or comprehensive, companies that respect users’ rights should clearly disclose when and how they will notify individuals who have been affected, or have likely been affected, by a data breach.

See the guidance for Indicator P15 of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#P15

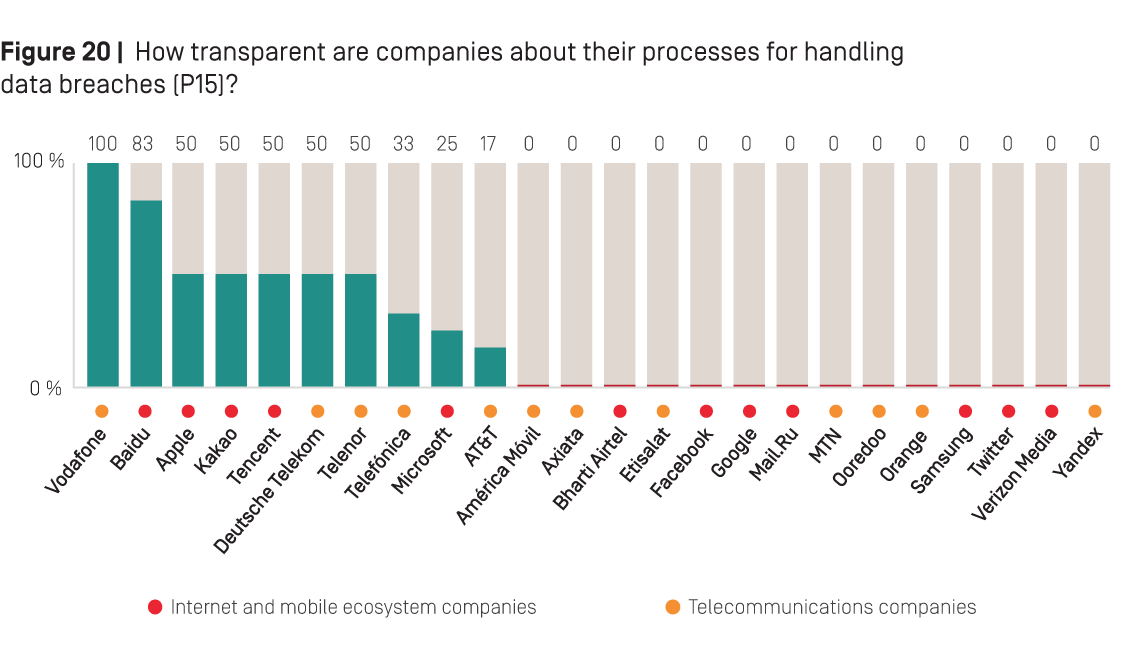

Results over the past three RDR Indexes indicate that companies are making steady progress. Data from the 2017 RDR Index showed that only three companies—Telefónica, AT&T, and Vodafone—disclosed anything about these processes. Telefónica revealed the most by committing to notify users in case of a breach and providing some information about steps for providing remedy. In the 2018 RDR Index, Apple joined this group—making it the only internet and mobile ecosystem company to receive any credit on Indicator P15—and Vodafone stood out for its comprehensive disclosure that earned it the top score on this indicator.

In this year’s Index, 10 of the 24 companies evaluated earned some points on Indicator P15—a trend that appears to be driven by new regulations in various jurisdictions requiring companies to be more accountable for how they handle data breaches. As Figure 20 below shows, Vodafone was again the only company to receive a full score on this indicator. It disclosed a clear commitment to notify the relevant authorities without undue delay when a data breach occurs, provided details about its process for notifying data subjects who might be affected by a data breach, and explained what kinds of steps it will take to address the impact of a data breach on its users.85

Both Chinese internet companies, Baidu and Tencent, received some credit on this indicator this year, likely due to stricter regulations in China requiring companies to have cybersecurity response plans that include user notification procedures.86 Baidu received the highest score on this indicator among internet and mobile ecosystem companies, disclosing more than Apple, Kakao, Tencent, and Microsoft. Tencent tied with Apple and Kakao for the second-best score on this indicator, and disclosed more than Microsoft.

But six of the 12 internet and mobile ecosystem companies evaluated—including Facebook, Google, Verizon Media, and Twitter—still failed to disclose even basic information about what procedures they have in place to respond to data breaches in the event that such incidents occur. The striking lack of disclosure by most U.S. internet and mobile ecosystem companies—which collectively are responsible for securing troves of data about users globally—may be explained by the fact that there is no legal requirement in the U.S. pushing companies to be more transparent. However, both Apple and Microsoft stood out for providing some information about how they deal with data breaches even though they are not legally required to do so.

The same holds true for Vodafone. Its comprehensive disclosure is a laudable example of a company going beyond what is legally required of companies in the EU. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)—which applies to all European telecommunications companies evaluated—requires “data controllers” to report breaches to authorities without “undue delay” and to notify affected users if the company deems that the breach could result in a high risk to the person’s privacy or security.87 But there is no particular requirement for companies to formally disclose these policies under the GDPR. This may explain why disclosure by these companies was so inconsistent: Deutsche Telekom, Telenor, and Telefónica all disclosed some information but each disclosed different things; Orange disclosed nothing at all.

Encryption is essential for enabling and protecting online expression and privacy—but many companies do not disclose if they are protecting users with the highest level of encryption available.

Encryption and anonymity are essential to exercising and protecting human rights, both on and offline.88 Yet over the last several years lawmakers around the world have passed measures undermining encryption—even giving authorities direct backdoors into user communications—in ways that human rights advocates say threaten fundamental privacy and freedom of expression rights.

For example, in Australia, the 2018 Assistance and Access Law gives broad authorities to the Australian government to compel tech companies to grant law enforcement agencies access to encrypted messages without the user’s knowledge.89 In the UK, the 2016 Investigatory Powers Act requires that network operators have the ability to “remove” end-to-end encryption.90 In China, the 2016 Cybersecurity Law allows the government to force companies to decode encrypted data.91 In Pakistan, the 2016 Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act criminalizes the use of encryption tools online.92 And in India, the proposed Intermediary Guidelines legislation includes a provision that would undermine the use of encryption by companies like WhatsApp.93

Types of encryption

There are different types of encryption, depending on the security objective and the type of product or service.

Encryption hides the content of communications so only the intended recipient can view it. The process uses an algorithm to convert the message into a coded format so that the message looks like a random series of characters. Only someone who has the decryption key can read the message. Data can be encrypted at different points: when it is in transmission and when it is stored (“at rest”).

Forward secrecy is an encryption method notably used in HTTPS web traffic and in messaging apps, in which a new key pair is generated for each session (HTTPS), or for each message exchanged between the parties (messaging apps). This way, if an adversary obtains one decryption key, they will not be able to decrypt past or future transmissions or messages in the conversation.

Forward secrecy is distinct from end-to-end encryption, which ensures that only the sender and intended recipient can read the content of the encrypted communications. Third parties, including the company, would not be able to decode the content. Many companies only encrypt traffic between users’ devices and the company servers, maintaining the ability to read communications content. They can then serve targeted advertising based on users’ data and share user information with the authorities.

See the RDR Index glossary of terms at: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#Glossary

The RDR Index has one indicator (P16) that evaluates how transparent internet and mobile ecosystem companies are about their encryption policies.94 Four elements measure if and how clearly companies disclose: if the transmission of user communications is encrypted by default; if the transmissions of user communications are encrypted using a unique key (what is referred to as “forward secrecy”); if users can secure their private content using end-to-end encryption (meaning not even the company can access the content); and if end-to-end encryption is enabled by default.

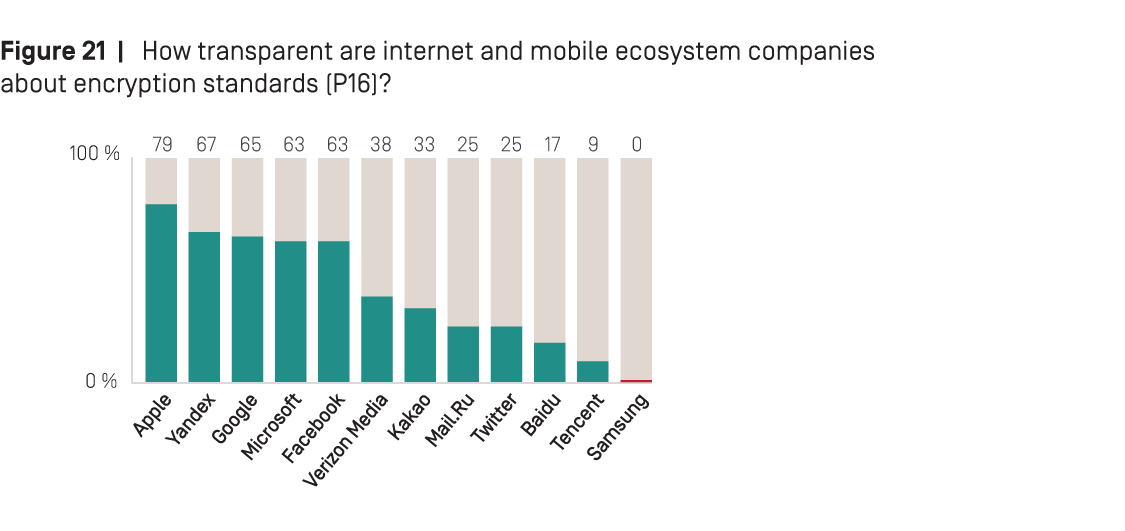

As Figure 21 below shows, Apple had the strongest encryption policies of any internet and mobile ecosystem company evaluated. It improved its disclosure of its encryption policies for iMessage and the iOS operating system, and clarified that it stores some user information in its iCloud cloud data service using end-to-end encryption so that even the company cannot access this data. As in previous years, the Russian internet company Yandex stood out for earning one of the top scores on this indicator, especially compared to the other Russian company in the RDR Index, Mail.Ru, which hardly disclosed any information about its encryption policies.

Google earned the third-best score on this indicator, after Apple and Yandex: it disclosed that it encrypts user traffic by default, but did not provide an option for users to end-to-end encrypt their private content or communications for Gmail, YouTube, or Google Drive. In 2018, Microsoft rolled out end-to-end encryption for Outlook and Skype, giving users the option to end-to-end encrypt their private communications, although it is not enabled by default. It also provided OneDrive cloud service users with the option to end-to-end encrypt their private content. However, Microsoft failed to disclose whether the transmissions of data are encrypted with unique keys for Bing and Skype. Facebook provided end-to-end encryption by default for WhatsApp, and gave Messenger users the option to enable end-to-end encryption, although it is not on by default. In contrast, it failed to disclose any information about its encryption practices for Instagram.

As found in previous RDR Indexes, Twitter disclosed less about its encryption standards than all of its U.S. peers. The company revealed that for Twitter (the social network), users’ internet traffic between their device and the company’s servers is encrypted by default and with forward secrecy—but it did not disclose similar information for Periscope. It also did not indicate if direct messages on Twitter are end-to-end encrypted (or clearly disclose that these messages are not secure).

Baidu and Tencent communicated more about the encryption of user communication and private content than in previous years, although they still disclosed very little compared to their peers. Increased transparency by both companies in similar areas may be in response to new guidelines issued in May 2018 that elaborate standards for compliance with China’s 2016 cybersecurity law.

Notably, Samsung remained the only company disclosing nothing about its encryption policies for either of the services evaluated (Android and Samsung Cloud). In contrast, its South Korean peer, Kakao, disclosed some information about its encryption policies for all three services evaluated (Daum Search, Daum Mail, and KakaoTalk). For KakaoTalk, it disclosed that users can encrypt their messages using end-to-end encryption, though this option is not on by default.

Companies should go beyond minimum legal requirements to ensure that users have control over what information is being collected and shared.

The EU’s new data protection regulations that became applicable in May 2018 spurred similar regulations in some other countries around the world, and public pressure for stronger regulation in many more.95 In China, lawmakers that same month issued guidelines reinforcing the country’s data protection and cybersecurity laws, including new rules requiring companies to be more transparent about what data is collected, used, and shared.96 In India, legislators in July 2018 submitted a draft bill that could codify into law the country’s landmark 2018 Supreme Court ruling that declared privacy a human right protected by India’s constitution.97 In South Africa, a new data protection law—modeled after the GDPR—is expected to take effect in 2019.98

In Europe, all 28 EU-member states are now bound by the GDPR’s tougher regulations aimed at giving users greater control over their personal data. Meanwhile, the EU is set this year to finalize the e-Privacy Regulation (ePR)—the so-called “cookie” law—which will work in tandem with the GDPR to regulate online platforms, messaging and voice applications (such as Skype and WhatsApp), and e-commerce sites, and may require consent for the use of cookies and other tracking technologies.99

While varying in focus and scope, these measures have put a spotlight on the importance of data privacy—and reflect a consensus among lawmakers, the public, and even by companies themselves of the necessity for more responsible data protection practices and standards.

New data protection regulations enacted or proposed since 2018

The following is a (non-exhaustive) list of data protection regulations, proposed or enacted since 2018 in jurisdictions where the companies evaluated in the RDR Index are headquartered.

European Union: In May 2018 the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) became applicable.100 The regulation sets data protection standards for any company (or “data controller”) that handles EU residents’ personal information.

China: In May 2018, the Personal Information Security Specification came into effect.101 Similar to GDPR principles, it clarifies the definition of personal information, and introduces obligations for how organizations should handle personal information. It sets guidelines for implementing China’s existing data protection rules—notably the 2016 Cybersecurity Law.102

India: In July 2018, India introduced a draft Personal Data Protection Bill which, if passed, would recognize privacy as a fundamental right in line with a landmark 2018 ruling by India’s Supreme Court.103 The Bill establishes a comprehensive data protection framework for India that defines the data rights of individuals and an enforcement framework that includes a data protection authority. The Privacy, Security, and Ownership of the Data in the Telecom Sector recommendations—which recognize the impact of automated decision-making on privacy—were issued concurrently.104

South Africa: In December 2018 the long-anticipated Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI)105 was officially published—although has yet to take effect. The law largely mirrors the GDPR, setting conditions for how companies should process personal information.

U.S. (California): The state of California passed a new law set to go into effect in January 2020 that grants Californians the right to be informed, at the time of personal information collection, what information is being collected and the purposes for which that information will be used.106

Results of the 2019 RDR Index are encouraging: most companies indeed appear to be taking concrete steps to do more to respect users’ privacy. Most companies evaluated updated their policies to comply with regulatory demands, and these changes have resulted in improved clarity by most companies about how they handle and secure user data.

At the same time, some globally operating companies have responded to regional regulations in ways that resulted in uneven privacy protections for their users. As the GPDR became applicable in May 2018, Facebook, for instance, rolled out a different privacy policy for WhatsApp users in the EU, offering greater options to access and control their data—including rights to export and delete their information. Notably, the U.S. version of WhatsApp does not offer those users the same options and rights as EU-based WhatsApp users, since U.S. users are not legally covered under the GDPR.

Results also reveal key areas where companies are making no or little progress—particularly around privacy-related issues where there are weak or no regulations pushing companies to improve. This is especially evident among European telecommunications companies—which, although bound by stricter data protection regulations under the GDPR, still lacked transparency around key issues affecting users’ privacy.

It is critical to note that the RDR Index does not evaluate a company’s GDPR compliance. The RDR Index evaluates how transparent companies are about relevant policies affecting users’ privacy based on 18 indicators in the RDR Index—a subset of which loosely overlap with certain GDPR provisions and principles related to obligations about handling user data. But the RDR Index evaluates a much wider range of privacy-related issues than are addressed by the GDPR—including how transparent companies are about how they handle government demands for user data and about their security policies and practices. And, while both the RDR Index and the GDPR draw from and encourage compliance with the same set of international human rights principles and frameworks that guarantee privacy as a universal human right, the RDR Index requires companies to publicly disclose their commitments and policies in this regard, whereas the GDPR does not consistently incorporate the same high standards of disclosure.

Meanwhile, the GDPR establishes minimum standards for how “data controllers”—in this case, companies—should disclose regarding their handling of personal data.107 But national regulations and individual companies can, and in many cases should, go beyond the GDPR’s minimum transparency requirements. Only then can users be better informed of what is happening to their data—as well as understand the risks associated with using a particular service or product—in order to make informed choices. Our results in fact show that European telecommunications companies that performed best on the RDR Index on different indicators in the Privacy category were those that went beyond the GDPR’s minimum requirements and disclosed more detail about how they handle and secure user information.

An example is the GDPR’s notification requirements regarding data breaches. The GDPR requires “data controllers” to report breaches to authorities without “undue delay” and to notify affected users if the company deems that the breach could result in a high risk to the person’s privacy or security.108 But companies are not necessarily required to publish a policy that describes their protocols for handling these incidents, or to publicly commit to notify or provide remedy to affected users—as is the standard set by the RDR Index. Indicator P15 of the RDR Index expects companies to clearly disclose their policies for responding to data breaches, including clearly committing to notifying affected users and detailing what steps they will take to address the impacts. In the absence of this disclosure, a victim of a data breach would have no idea what steps the company takes after a breach has occurred or how to hold a company accountable in case these steps are not followed. Vodafone stood out as an example of a company that went beyond the GDPR’s minimum requirements pertaining to data breaches by publishing a policy clearly outlining its process for handling data breaches, including its procedures for notifying authorities, and affected users, as well as describing its policies for providing remedy when these incidents occur.

Another key gap in the GDPR is around government demands. The scope of the GDPR specifically excludes this aspect of data privacy, which means companies are not obliged under the GDPR to disclose their relationships with governments or law enforcement, or their processes for responding to government demands to hand over or otherwise access user information.109 The RDR Index, however, expects robust transparency in these areas. While we recognize that telecommunications companies in Europe and in many jurisdictions around the world are often prohibited by national security laws from disclosing actual data about the government demands they receive and comply with, we expect companies to publish as much information as is legally permissible. At the very least, companies should explain their processes for handling such requests—which typically is not legally prohibited, even in the most restrictive environments—and, ideally, publish data revealing the number and types of requests they receive and comply with and to commit to informing users when their data has been requested. Companies should clearly specify the legal reasons preventing them from being fully transparent in these areas. Notably, these transparency standards follow industry best practices, including those set by GNI.110

Meanwhile, the proposed e-Privacy Regulation (ePR) may address at least some of these gaps—or so many experts and advocates hope.111 The regulation is intended to fill in details about how “data controllers” should implement and comply with the GDPR, and will also cover a range of issues that fall outside the GDPR’s current scope. Some advocacy groups, including Access Now, are pushing to include requirements for companies to publish yearly transparency reports about how they handle government demands, and to provide users clear avenues to seek remedy in case of privacy abuses.

1. Go beyond legal compliance: Regulations alone do not ensure that companies are doing enough to respect users’ privacy. Companies should go beyond what may be legally required to ensure they are protecting and respecting users’ fundamental human right to privacy.

2. Maximize transparency: Companies should disclose the maximum possible information about policies affecting users’ privacy, including their handling of user information and options users have to control what data is collected, shared, and how it is used. Companies should supply users with the information they need to give meaningful consent for how their data is managed.

3. Disclose government demands: Companies should publish regular transparency reports, including descriptions and data about actions they take in response to government demands to hand over user information, and disclose any legal reasons preventing them from being fully transparent in this area. They should also commit to notifying users when their data has been requested or provide legal justifications for when they are unable to do so.

4. Demonstrate a credible commitment to security: Companies should disclose whether and to what extent they follow industry standards of encryption and security, conduct security audits, monitor employee access to information, and educate users about threats.

5. Strengthen governance of privacy commitments: Implement effective governance and oversight of risks to users’ privacy posed by governments as well as by all other types of actors who may gain access to their information. Provide accessible, predictable, and transparent grievance and remedy mechanisms that ensure effective redress for violations of privacy, in line with the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

6. Apply privacy protections universally: Companies should implement privacy policies that offer the highest possible protections in all of the markets in which they operate, respecting the human rights of all users equally, regardless of geographic location.

1. Prioritize transparency: Privacy laws and data protection regulations should include strong transparency and disclosure requirements so that users can make informed decisions about whether and how to use a product or service, and exercise meaningful control over how a company can use their information.

2. Reform surveillance laws: Surveillance-related laws and practices should be reformed to comply with the 13 “Necessary and Proportionate” principles,113 a framework for assessing whether current or proposed surveillance laws and practices are compatible with international human rights norms.

3. Be transparent: Governments should publish accessible information and relevant data about all requirements and demands made by government entities (national, regional, and local) to hand over or otherwise access user data. For government members of the Open Government Partnership—an organization dedicated to making governments more open, accountable, and responsive to citizens—transparency about requests and demands made to companies affecting privacy should be considered a fundamental part of that commitment.

4. Support encryption: Governments should not weaken or undermine encryption standards, ban or limit users’ access to encryption, or enact legislation requiring companies to provide “backdoors” or vulnerabilities that allow for third-party access to unencrypted data, or to hand over encryption keys.

5. Require strong corporate governance: As described in Chapter 3, governments should require companies to carry out credible due diligence, assessing the impact and risks of their operations and policies on users’ privacy. Companies should also be required to provide meaningful grievance and remedy mechanisms, and to ensure that the law enables meaningful legal recourse and remedy for violations of privacy.

6. Engage with stakeholders: Work with civil society, companies, and other governments to develop and enforce effective, constructive regulation that prioritizes the human rights of all internet users.

[70] “2019 Indicators: Privacy,” Ranking Digital Rights, rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#P

[71] “2018 Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index” (Ranking Digital Rights, 2018), rankingdigitalrights.org/index2018/assets/static/download/RDRindex2018report.pdf

[72] “Information Security Technology – Personal Information Security Specification (GB/T 35273-2017)” (Standardization Administration of China, May 2018)

[73] See the 2019 RDR Index methodology at: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators

[74] See the 2019 RDR Index methodology at: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#P7

[75] “Targeted Advertising and Lack of User Control,” 2018 Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index, rankingdigitalrights.org/index2018/report/privacy-failures/#section-53

[76] Freedom on the Net 2018, Freedom House, freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/freedom-net-2018/rise-digital-authoritarianism

[77] “H.R. 2048 - USA Freedom Act of 2015” (114th Congress, 2015), www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2048

[78] “How do we share, transfer, and publicly disclose your personal information?” Baidu Privacy Policy, accessed April 25, 2019, www.baidu.com/duty/yinsiquan-policy.html

[79] Kurt Wagner, “Facebook employees had access to private passwords for hundreds of millions of people,” Recode, March 21, 2019, www.recode.net/2019/3/21/18275917/facebook-passwords-privacy-encryption-employees-access

[80] “DLA Piper GDPR data breach survey: February 2019,” DLA Piper, February 6, 2019, www.dlapiper.com/en/uk/insights/publications/2019/01/gdpr-data-breach-survey

[81] Aja Romano, “Facebook says 50 million user accounts were exposed to hackers,” Vox, September 28, 2019, www.vox.com/2018/9/28/17914598/facebook-new-hack-data-breach-50-million

[82] Vidhi Doshi, “A security breach in India has left a billion people at risk of identity theft,” Washington Post, January 4, 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2018/01/04/a-security-breach-in-india-has-left-a-billion-people-at-risk-of-identity-theft

[83] 2017: Poor Internal Security Practices Take a Toll,” The Breach Level Index (Gemalto, 2017), breachlevelindex.com/assets/Breach-Level-Index-Report-H1-2017-Gemalto.pdf

[84] Niall McCarthy, “The Average Cost Of A Data Breach Is Highest In The U.S.[Infographic],” Forbes, July 13, 2018, www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2018/07/13/the-average-cost-of-a-data-breach-is-highest-in-the-u-s-infographic/#1b55d30c2f37

[85] “Vodafone Group FAQs on Privacy and Security,” (Vodafone Group, December 2017), www.vodafone.com/content/dam/vodafone-images/sustainability/downloads/VodafoneGroupFAQsonPrivacyandSecurity_December2017.pdf

[86] “Information Security Technology - Personal Information Security Specification” (Standardization Administration of China, May 2018), www.tc260.org.cn/upload/2018-01-24/1516799764389090333.pdf

[87] See Articles 33 and 34 of “Regulation 2016/679/EU on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)” (European Parliament and European Council, April 27, 2016), eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

[88] “A/HRC/29/32: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression” (United Nations Human Rights Council, May 22, 2015), ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/29/32

[89] “Australia data encryption laws explained,” BBC News, December 7, 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-46463029

[90] Siobhan Conners, “What is the Investigatory Powers Act 2016?,” IT PRO, April 10, 2019, www.itpro.co.uk/policy-legislation/33407/what-is-the-investigatory-powers-act-2016

[91] Yuan Yang, “China’s cyber security law rattles multinationals,” Financial Times, May 30, 2017, www.ft.com/content/b302269c-44ff-11e7-8519-9f94ee97d996

[92] Ramsha Jahangir, “UN expert urges countries to protect right to privacy in digital age,” DAWN, September 11, 2018, www.dawn.com/news/1432243

[93] Kurt Wagner, “WhatsApp is at risk in India. So are free speech and encryption,” Recode, February 11, 2019, www.recode.net/2019/2/19/18224084/india-intermediary-guidelines-laws-free-speech-encryption-whatsapp

[94] See the 2019 RDR Index methodology at: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#P16

[95] “Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)” (European Union, April 5, 2016), eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679

[96] “Information Security Technology – Personal Information Security Specification (GB/T 35273-2017)” (Standardization Administration of China, May 2018), std.sacinfo.org.cn/gnoc/queryInfo?id=5765F72B812F670F1571443FF09C12D2

[97] “The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018” (Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, July 27, 2018). meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/Personal_Data_Protection_Bill,2018.pdf

[98] “Protection of Personal Information Act, 2013 (Act No. 4 of 2013): Regulations Relating to the Protection of Personal Information (Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, December 14, 2018), www.justice.gov.za/inforeg/docs/20181214-gg42110-rg10897-gon1383-POPIregister.pdf

[99] “Proposal for an ePrivacy Regulation” (European Commission, January 2017), ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/proposal-eprivacy-regulation

[100] “Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)” (European Union, April 5, 2016), eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

[101] “Information Security Technology – Personal Information Security Specification (GB/T 35273-2017)” (Standardization Administration of China, May 2018).

[102] “2016 Cybersecurity Law” (Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, November 7, 2016), www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/cybersecuritylaw

[103] “The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018” (Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, July 27, 2018).

[104] “Recommendations on Privacy, Security, and Ownership of the Data in the Telecom Sector” (Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, July 16, 2018), main.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/RecommendationDataPrivacy16072018_0.pdf

[105] Protection of Personal Information Act, 2013 (Act No. 4 of 2013): Regulations Relating to the Protection of Personal Information (Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, December 14, 2018).

[106] “Assembly Bill No. 375 Chapter 55: An Act to Add Title 1.81.5 (Commencing with Section 1798.100) to Part 4 of Division 3 of the Civil Code, Relating to Privacy, Also Known as California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (‘CCPA’)” (California Legislature, June 29, 2018), leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB375

[107] See Articles 5(1)(a) and the information obligations in Articles 12, 13, and 14 of the “Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)” (European Union, April 5, 2016).

[108] See Articles 33 and 34 of the “Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)” (European Union, April 5, 2016).

[109] According to Articles 2(2)(d) the processing of personal data by authorities for the purposes of crime prevention, investigations, and safeguarding public security are not within the scope of the GDPR. “Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)” (European Union, April 5, 2016).

[110] “The GNI Principles,” Global Network Initiative, accessed April 23, 2019, globalnetworkinitiative.org/gni-principles

[111] “Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the respect for private life and the protection of personal data in electronic communications and repealing Directive 2002/58/EC (Regulation on Privacy and Electronic Communications)” (European Commission, October 1, 2017), eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52017PC0010

[112] “Access Now’s comments to the proposed e-Privacy Regulation” (Access Now, June 2017), www.accessnow.org/cms/assets/uploads/2017/06/ePrivacy-paper-amendments-Access-Now.pdf

[113] “International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance” (Necessary and Proportionate, May 2014), necessaryandproportionate.org/principles