Companies that led the RDR Index have stronger governance. Yet governance of human rights risks faced by users remains inconsistent and uneven.

Strong governance and oversight are essential for companies to assess risks to users and mitigate harms. Without clear commitment, oversight, risk assessment, stakeholder engagement, and remedy mechanisms, even companies with good practices in certain areas—such as strong data security or robust efforts to shield users from overbroad government censorship demands—are vulnerable to serious blind spots regarding other types of risks that their users may face. Nor are they in a position to identify and mitigate harms caused by new products and technologies at a relatively early stage before they become entrenched.

While many countries are enacting new regulations focused on data protection and curbing violent extremism, the 2019 RDR Index reveals serious and persistent gaps in corporate governance that are largely unaddressed by regulators.

The Governance category of the RDR Index evaluates if companies show that they have clear processes and mechanisms in place to ensure that commitments to respect human rights—specifically freedom of expression and privacy—are made and carried out across their global business operations. A company’s efforts to implement these commitments should follow, and ideally surpass, the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), and other industry-specific human rights standards focused on freedom of expression and privacy, in particular the Global Network Initiative (GNI) Principles. Measures should include board and corporate-level oversight, internal accountability mechanisms, risk assessment, and grievance mechanisms.

The 2019 RDR Index shows that despite persistent gaps, most companies continue to make progress in this area. As was also the case between 2017 and 2018, the Governance category of the RDR Index saw the greatest overall score increase in the past year, with 11 companies making some improvements to at least one of the six indicators evaluating corporate governance of freedom of expression and privacy issues.

Evaluating corporate governance of human rights

What the RDR Index evaluates: The Governance category of the RDR Index contains six indicators that assess if companies make a clear commitment to respect and protect human rights—specifically freedom of expression and privacy—and have clear processes and mechanisms in place to ensure that these commitments are implemented across their global business operations. Indicators evaluate:

- Human rights commitment (G1): Does the company make an explicit statement affirming their commitment to freedom of expression and privacy as human rights?

- Senior-level oversight (G2): Does the company provide clear evidence of senior-level oversight over freedom of expression and privacy?

- Employee training (G3): Does the company disclose if there are employee training and whistleblower programs addressing these issues?

- Due diligence (G4): Does the company conduct human rights due diligence and impact assessments to identify the impacts of the company’s products, services, and business operations on freedom of expression and privacy?

- Stakeholder engagement (G5): Does the company engage in systematic and credible stakeholder engagement, ideally including membership in a multi-stakeholder organization committed to human rights principles including freedom of expression and privacy?

- Remedy (G6): Does the company offer clear grievance and remedy mechanisms enabling users to notify the company when their freedom of expression and privacy rights have been affected or violated in connection with the company’s business, plus evidence that the company provides appropriate responses or remedies?

See the Governance category of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#G

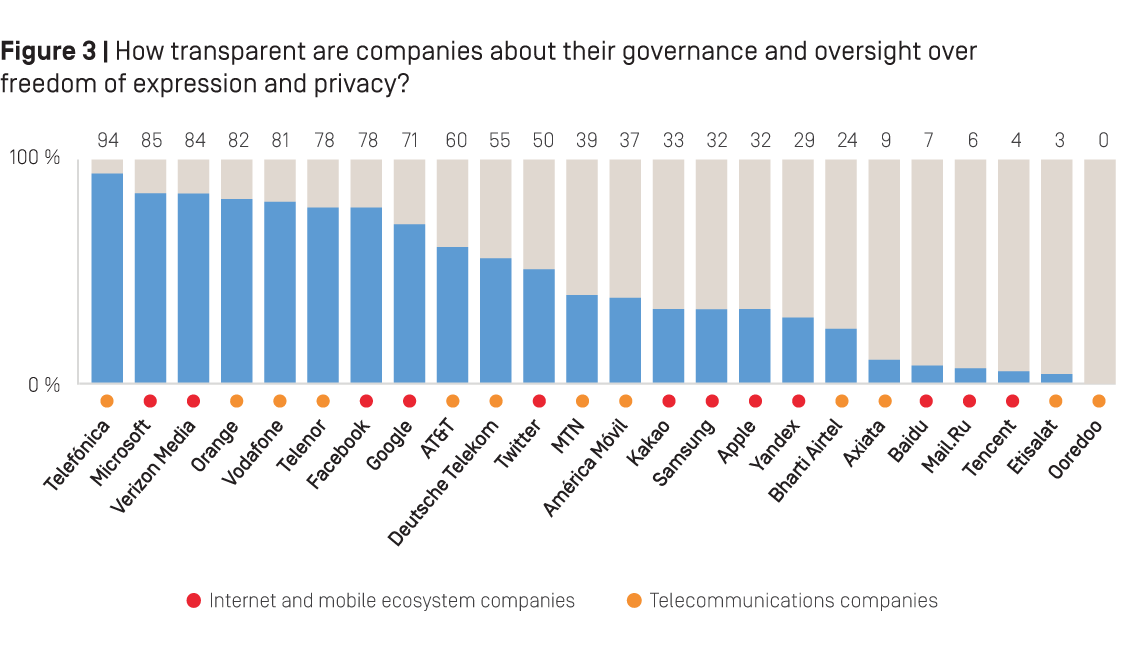

As in previous iterations of the RDR Index, the top governance scores this year all went to companies that are members of GNI, a multi-stakeholder organization that focuses on upholding principles of freedom of expression and privacy, primarily in relation to government requests.28 GNI-member companies commit to a set of principles and Implementation Guidelines, including implementing human rights due diligence processes as well as transparency and accountability mechanisms. Members also undergo an independent third-party assessment to verify if they are implementing these commitments, the results of which are then approved by a multi-stakeholder governing board made up of human rights organizations, investors, and academics, in addition to company representatives.

As Figure 3 above shows, Telefónica earned a solid “A” in governance. The company received the top score on all six indicators in this category, disclosing more than any other company in the RDR Index about its governance and oversight over human rights issues across its global business operations. Among other areas, Telefónica stood out for its especially strong remedy mechanisms in comparison to other companies in the RDR Index (see section 3.4).

Along with Telefónica, GNI members Microsoft, Verizon Media, Orange, and Vodafone all disclosed strong governance of freedom of expression and privacy issues—all earning scores of over 80 percent in this category. Each of these companies disclosed a clear policy outlining a commitment to respect users’ human rights, senior-level oversight over human rights issues, and internal mechanisms to implement these commitments. Orange and Verizon Media both improved their disclosure of their human rights due diligence practices.

Orange’s strong performance in the Governance category stands in notable contrast to its weaker performance in other areas of the RDR Index, particularly in relation to other telecommunications companies in the GNI. A 2017 law in France requiring a “duty of vigilance” for multinational corporations means that human rights oversight and risk assessment are now mandatory for Orange.29

GNI member Google lagged behind its GNI peers for notably weaker and inconsistent governance and management of human rights commitments and policies. Google made some progress this year by specifying that the board indeed has oversight over privacy issues (G2)—which the company had failed to clarify since re-organizing under Alphabet in 2015. But Google continued to fall significantly short of providing clear, accessible grievance and remedy mechanisms, particularly in comparison to other companies (G6).

Twitter, which is not a GNI member, disclosed almost no evidence of its human rights due diligence efforts (G4) and failed to disclose if the board oversees freedom of expression and privacy issues (G2).

Apple and Samsung tied at 32 percent on governance. Neither company is a GNI member. Apple’s low score in this category—it was the only U.S.-based company to score under 50 percent—was due to its failure to disclose any commitments to respect freedom of expression. While Apple in 2018 took a big step forward by issuing a statement acknowledging privacy as a fundamental human right30—and outlining its commitment to protect that right—the company has consistently failed to recognize freedom of expression as a human right or make any commitment to protect the freedom of expression rights of its users. Given Apple’s growing focus on content for revenue growth and the role of its App Store and the iTunes content platform as gatekeepers of speech, it is problematic that the company provides no evidence of governance and oversight over freedom of expression issues whatsoever (see section 3.2).

On the positive side, a handful of non-GNI-member companies took concrete steps to improve their corporate governance and oversight of human rights issues:

Most companies’ corporate governance policies and practices focus on privacy risks and sideline freedom of expression.

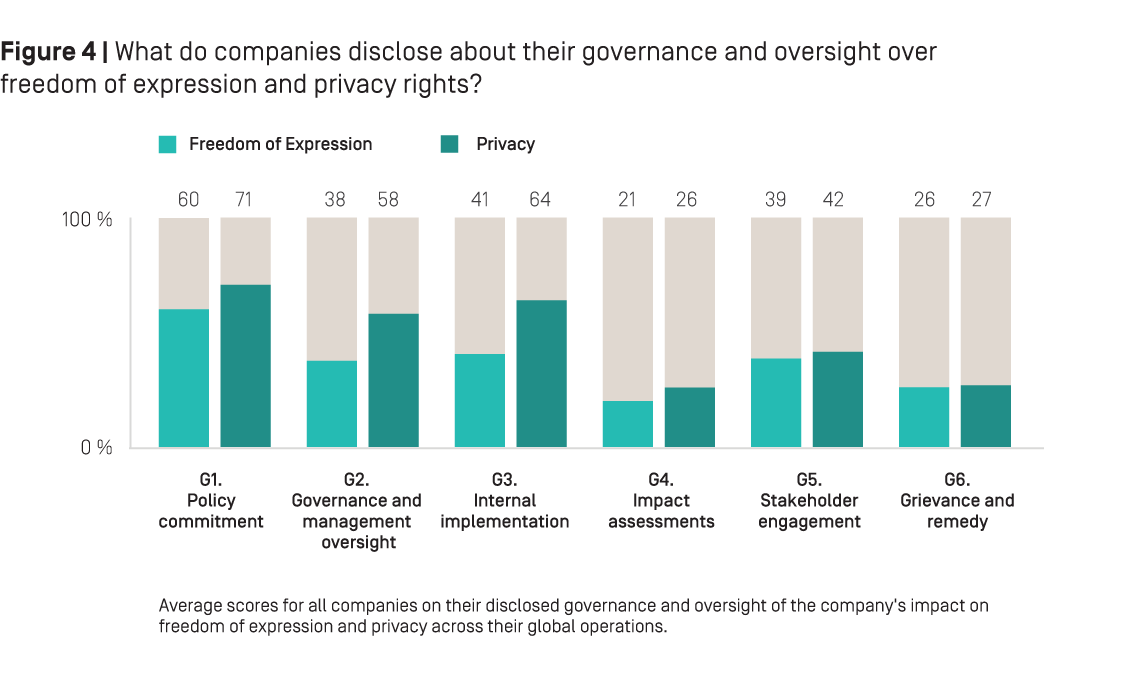

Freedom of expression and privacy are interdependent and complementary rights. Privacy is a “gateway” to freedom of expression: it enables people to organize and discuss opinions and ideas, or to conduct research and interview sources to determine the facts of a situation prior to reporting it, without fear of retribution prior to publication.33 Once information is shared publicly, or as it is being uploaded to a platform or transmitted through a service provider or device, it is at risk of censorship. Corporate commitment to both rights is therefore equally important. Yet most companies in the RDR Index displayed a weaker commitment to respect users’ freedom of expression than to users’ privacy, disclosing less oversight, due diligence, or other processes to identify and mitigate threats to users’ freedom of expression.

As Figure 4 above indicates, most companies in the RDR Index—15 out of 24—did commit to respect both freedom of expression and privacy. However, four companies—Apple, Baidu, Kakao, and Tencent—made a formal public commitment to respect users’ privacy but made no similar commitment to protect freedom of expression.

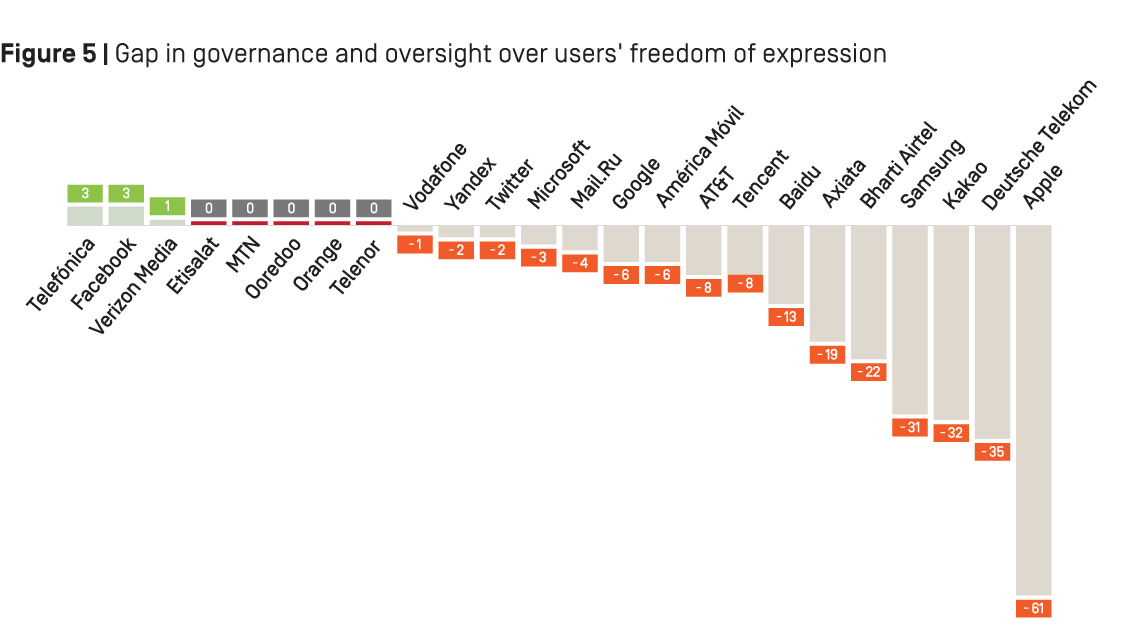

As Figure 5 below shows, Apple had the biggest gap in its governance of freedom of expression issues as compared to privacy. It was the only company in the entire RDR Index to receive full credit for its commitment to privacy as a human right and no credit for making a similar commitment to freedom of expression. The company earned a small amount of credit on just one indicator in this category (G6)—for disclosing some information about how app developers can file complaints if they feel that Apple has violated their freedom of expression rights if the company rejects an app from the App Store—but otherwise failed to disclose any information about its governance and oversight over freedom of expression issues at the company.

Deutsche Telekom, Kakao, Samsung, Bharti Airtel, and Axiata also had noticeable gaps in their disclosure, providing far less evidence of their governance and oversight over freedom of expression commitments and policies than those related to privacy. Deutsche Telekom failed to disclose if there is senior-level oversight over freedom of expression issues at the company (G2) and fell short on disclosing evidence that it conducts human rights risk assessments around impacts of its business operations, products, and services on users’ freedom of expression rights (G4).

Samsung and Kakao lacked disclosure of governance over freedom of expression in relation to privacy in similar areas: neither company disclosed any evidence of senior-level management over issues related to freedom of expression (G2), of providing employee training on these issues (G3), or of carrying out risk assessments associated with how their business operations, products, and services affect users’ freedom of expression (G4).

Notably, three companies—Facebook, Telefónica, and Verizon Media—disclosed slightly more about their governance and oversight over freedom of expression as compared to their governance over privacy. Facebook in April 2018 launched a new appeals process for users to seek redress for wrongfully removed content, but it does not offer a clear mechanism for users to report complaints if they feel their privacy rights have been violated by the company.

Few companies are prepared to anticipate human rights risks and mitigate harms.

A company that commits to respect human rights cannot credibly fulfill such a commitment without conducting regular and comprehensive assessments to understand how its products, services, and business practices affect human rights, and how any harms should be prevented or mitigated. Companies in the ICT sector that commit to respect users’ freedom of expression and privacy should therefore be expected to conduct human rights risk assessments (HRIAs) on how users’ rights are affected by all aspects of their business—from questions of technical design to how and where they make their services available.34

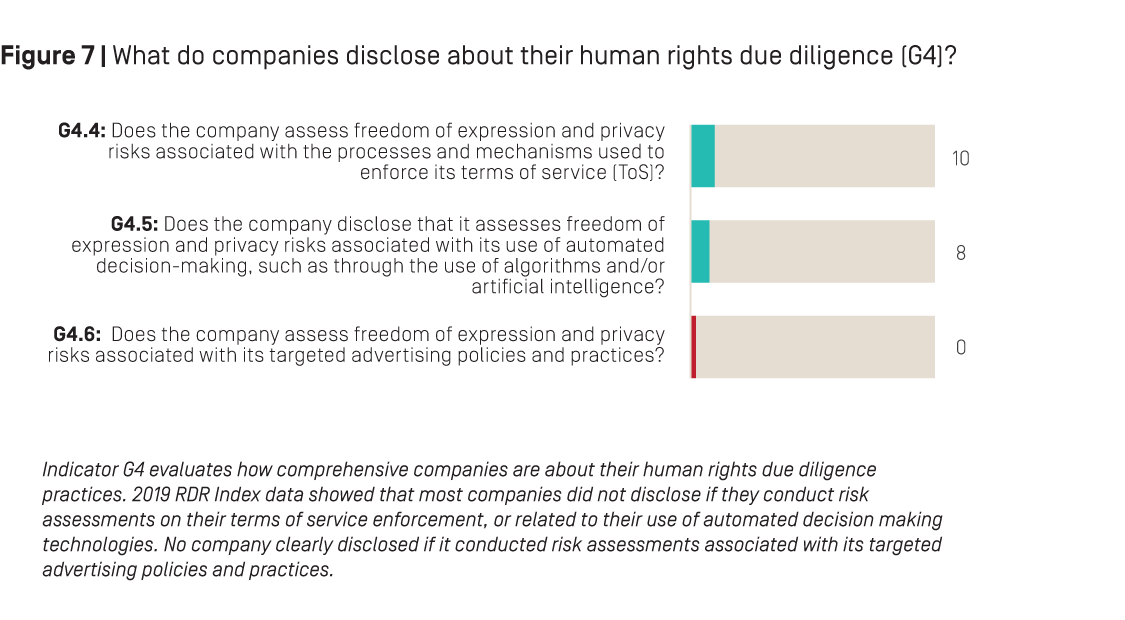

Indicator G4 evaluates if companies carry out regular, comprehensive, and credible due diligence, such as human rights impact assessments, in order to identify how their business operations, products, and services affect freedom of expression and privacy and to mitigate any risks posed by those impacts.35

Evaluating human rights due diligence

What the RDR Index evaluates: Indicator G4 evaluates if companies conduct risk assessments to evaluate and address the potential adverse impact of their business operations on users’ human rights. We expect companies to carry out credible and comprehensive due diligence in order to assess and manage risks related to how their products or services may impact users’ freedom of expression and privacy.

For the 2019 RDR Index, this indicator was expanded to address due diligence efforts by companies regarding their use of automated decision-making tools, as well as their targeted advertising policies and practices. Specifically, two new elements were added in order to evaluate if companies conduct risk assessments associated with their use of automated decision-making tools (such as through algorithms and artificial intelligence), and regarding their targeted advertising policies and practices.

Read the guidance for Indicator G4 of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#G4.

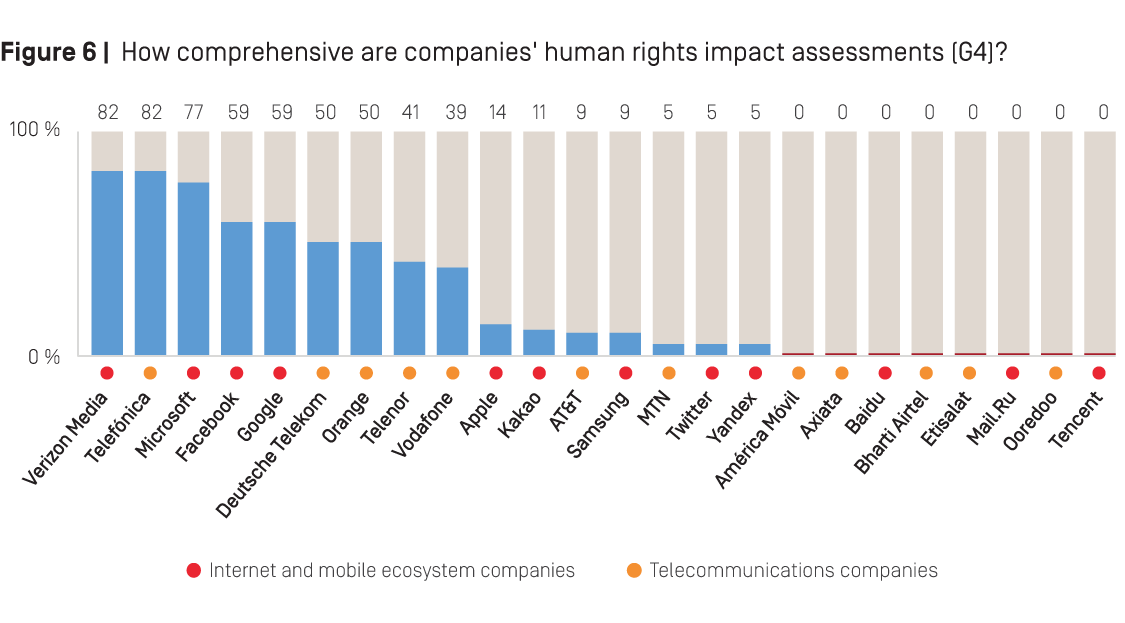

Few companies in the RDR Index are positioned to understand human rights risks or manage possible harms. Most of the 24 companies evaluated disclosed weak or inconsistent evidence of their human rights due diligence efforts—eight companies (all telecommunications companies) gave no indication that they conduct any risk assessments whatsoever.

As Figure 6 below shows, GNI-member companies disclosed more about their due diligence overall than companies that are not GNI members, but in comprehensiveness and scope, disclosure was uneven.

Telefónica and Verizon Media led the pack, disclosing more about their due diligence efforts than all other companies. Both companies disclosed risk assessment processes that were more comprehensive and systematic in relation to their peers: they assess risks when launching new services or entering new markets and they consider how laws in the jurisdictions where they operate might affect freedom of expression and privacy. In contrast to most other companies evaluated, Telefónica and Verizon Media disclosed that they assess risks associated with their enforcement of their terms of service, and that their assessments are conducted on a regular schedule and assured by a third party. Telefónica was one of only three companies in the RDR Index—including Microsoft and Deutsche Telekom—to disclose any information about assessing risks associated with its use of automated decision-making technologies.

Apple and Twitter—neither of which are GNI members—provided significantly less information about their due diligence practices than their peers, making it unclear whether either company has mechanisms in place to anticipate and manage human rights risks associated with their business operations and practices. Twitter disclosed the least information about its due diligence efforts of any U.S. company in the Index. It disclosed that its Trust and Safety team considers the impact of decisions such as entering new markets or releasing new products, but it failed to disclose whether it conducts systematic human rights impact assessments at all. Apple disclosed that it assesses the privacy risks of its existing and new products and services, but disclosed nothing about whether it assesses risks related to freedom of expression.

Most companies did not disclose if they assess risks related to their use of automated decision-making technologies, targeted advertising, or their terms of service enforcement.

As Figure 7 below shows, most companies revealed little or nothing about whether they conduct risk assessments associated with their targeted advertising policies and practices, their use of automated decision-making technologies, or their enforcement of terms of service—all key issues that have a critical and direct impact on users’ human rights.

Results showed that:

No matter how comprehensively a company assesses its human rights risks and impacts, no company is perfect. Deliberate and inadvertent harms will inevitably occur, either from the company itself or by a third-party organization. Therefore, a company committed to respecting users’ freedom of expression and privacy cannot fully meet its commitment without establishing meaningful and effective mechanisms for users to report harms and obtain redress.

Evaluating effective grievance and remedy

What the RDR Index evaluates: The RDR Index includes one indicator, G6, evaluating if companies offer clear and accessible complaints mechanisms enabling users to seek remedy if they feel their freedom of expression or privacy has been violated by the companies’ actions or policies.

For the 2019 RDR Index, this indicator was revised in order to more closely align with the standards for remedy outlined in Principle 31 of the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which states that in order to be effective, a company’s remedy procedures should be clear, accessible, predictable, and transparent. The revised Indicator G6 in the 2019 RDR Index therefore expects companies to provide users with a clear mechanism to submit grievances related to freedom of expression and privacy, to clearly disclose its remedy procedures and steps it takes to redress human rights grievances, and to offer evidence it is responding to and providing redress for these types of complaints.

Read the guidance for Indicator G6 of the RDR Index methodology: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#G6.

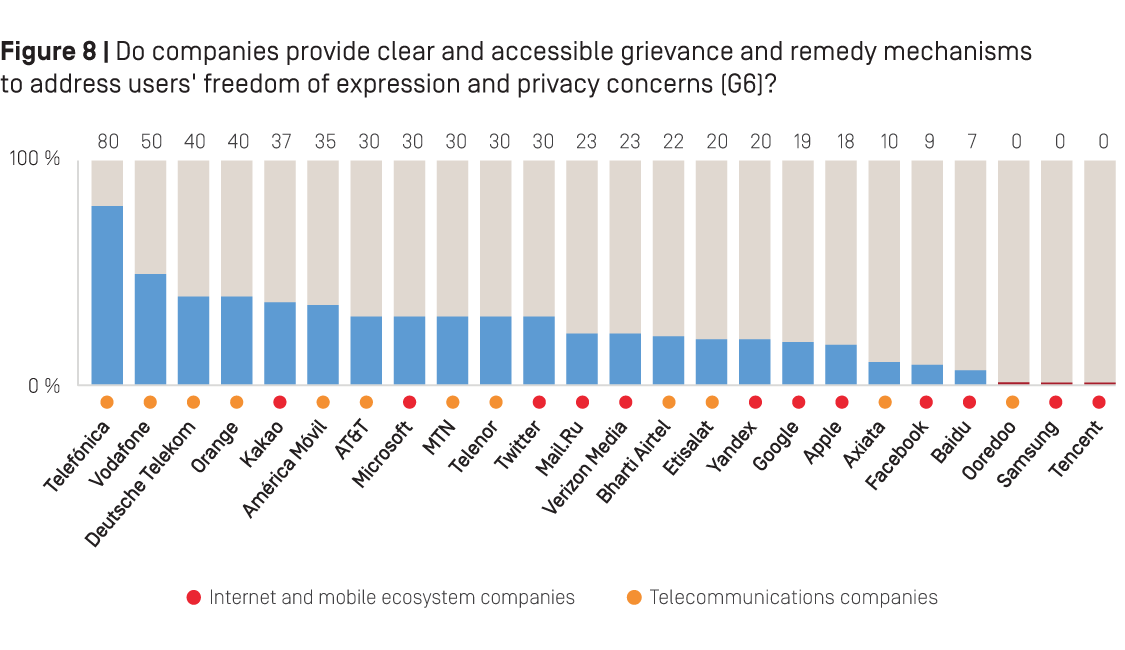

As Figure 8 below shows, four of the five European telecommunications companies in the RDR Index—Telefónica, Vodafone, Orange, and Deutsche Telekom—earned the top scores on this indicator.

Telefónica once again had the clearest disclosure of a grievance and remedy mechanism of any company in the RDR Index, with some improvements for 2019. The company’s “Responsible Business Channel”—an online portal that lets anyone file a complaint if they feel their rights have been violated—sets an example for how companies can offer a clear, accessible mechanism for users to submit human rights grievances. Telefónica also disclosed more about its processes for providing redress than any of its peers—and it was one of just five companies to disclose any evidence that it is actually responding to these complaints.

While GNI-member companies generally had stronger disclosure of governance and oversight over human rights issues—and therefore scored higher on this category of the RDR Index in comparison to their non-GNI member peers—this is one area where GNI membership was not a predictor of strong performance. As Figure 8 above shows, numerous non-GNI member companies—including Kakao and América Móvil—had more transparent appeals mechanisms than some GNI-member companies. Kakao’s stronger disclosure was largely due to requirements under South Korean law—although Kakao went beyond the legal requirements by providing users with an appeals mechanism for when content is removed in response to defamation claims.

As we found in previous years, Facebook’s grievance and remedy mechanisms were among the weakest of any company in the RDR Index—even after introducing improvements to its appeals process over the last year.37 In April 2018, the company unveiled a new process for remedying wrongful takedowns of content on Facebook (the social network), but it was not clear if this mechanism covers any violation of its Community Guidelines. Meanwhile, the company lacked a clear appeal mechanism allowing users to seek remedy in cases where they feel that Facebook has violated their privacy.

Google’s grievance and remedy mechanisms were slightly stronger than Facebook’s, but still weaker than most of its peers. The company only gave options for users to appeal certain actions that could impact freedom of expression or privacy, such as copyright takedown decisions, account restrictions, or sharing user data. It was unclear if users could submit complaints about other types of actions that a user felt infringed on their freedom of expression or privacy. Google also offered hardly any evidence that it provides effective remedy for these complaints.

Governments have a role to play in ensuring that companies exercise appropriate governance and oversight of human rights risks, including risks to users’ freedom of expression and privacy.

In outlining a framework for how companies should respect human rights, the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) emphasize the importance of commitment, oversight, stakeholder engagement, due diligence, and remedy. A growing number of governments have either published national action plans for advancing the adoption of the UNGPs by companies under their jurisdiction or have announced plans to do so.38 Thus far, critics point out that few governments address threats to the human rights of internet users in their national action plans and the governments of many advanced economies focus narrowly on the overseas operations of their multinationals.39

It is nonetheless notable that some jurisdictions are starting to convert soft commitments into hard law, starting with basic reporting and disclosure requirements. The EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive, adopted in 2014, requires large companies to publish regular reports on the social and environmental impacts of their activities, including “respect for human rights.”40 All member states have transposed the directive into law.

However, analysis of company disclosures has found it to be uneven and insufficiently specific, particularly in relation to human rights due diligence.41

Meanwhile, laws are emerging that specifically require risk assessment. In 2017, in France, a new “duty of vigilance” law went into force for French multinationals, making strong human rights oversight and risk assessment mandatory.42 In early 2019 the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development was reported to have drafted a mandatory human rights due diligence law for German companies.43 A group of EU parliamentarians have developed an action plan for the next European Commission to draft a law requiring European companies to conduct human rights due diligence.44 The cross-sector business and human rights movement is pushing for similar legal mandates around the world, potentially requiring companies and their investors to conduct due diligence on the full range of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks faced by companies in their global operations.45

Other jurisdictions require companies to establish grievance and remedy mechanisms through which users can lodge complaints and receive redress when their rights are violated in connection with a company’s business. Indian law requires Bharti Airtel’s domestic operating company, Airtel India, to have grievance officers as well as a redress mechanism. Kakao’s score on remedy was bolstered by its compliance with South Korea’s data protection regime which includes the right to make complaints and seek remedies.

As the 2019 RDR Index results show, companies can certainly do much more to improve their governance of human rights risks even when governments fail to support and enable high standards of corporate respect for users’ freedom of expression and privacy. U.S. companies that now disclose relatively strong governance mechanisms in relation to users’ rights have done so in the absence of any regulatory requirements.

Some European companies also disclosed stronger governance than the law requires. For example: while Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) requires EU states to appoint an independent authority to oversee privacy issues and grants every “data subject” the right to file with that authority grievances related to possible violations, companies are under no obligation under the GDPR to have or to disclose grievance and remedy procedures. There is also no obligation for companies to disclose if and how they redress human rights harms. Instead, the Spanish multinational Telefónica, with its relatively strong grievance and remedy mechanisms, disclosed policies consistent with its voluntary commitment to the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which stipulate that companies as well as governments have an obligation to offer channels for grievance and remedy to those whose rights have been violated in connection with the company’s business.

Despite the laudable voluntary measures being taken by a number of companies, many others are failing to improve their governance of risks to users’ human rights of their own accord, thus underscoring the need for thoughtful regulation requiring appropriate due diligence, oversight, and remedy.

1. Conduct human rights impact assessments: Companies should conduct comprehensive due diligence for all aspects of their business that may affect users’ human rights. These include: government and other third-party demands affecting privacy or expression, private terms of service enforcement mechanisms such as content moderation, aspects of the business model such as targeted advertising, and the application of emerging technologies such as automation and machine learning.

2. Strengthen oversight: Companies’ boards of directors should exercise direct oversight over risks related to user security, privacy, and freedom of expression. To that end, board membership should include people with expertise and experience on issues related to digital rights. Boards should ensure that due diligence, remedy processes, and stakeholder engagement are effective enough to address and mitigate human rights impacts and risks.

3. Commit to third party assessment based on international human rights standards: Companies should join the Global Network Initiative or other similar multi-stakeholder organizations that can independently assess and verify whether they are implementing their due diligence and governance processes.

4. Establish effective and accessible grievance and remedy mechanisms: These mechanisms should cover user complaints about violations of their rights to freedom of expression as well as privacy.

5. Engage with affected stakeholders: Companies should engage with those who face a high risk of human rights violations, working with these individuals and groups to co-create new processes for identifying risks, mitigating harm, receiving grievances, and providing meaningful remedy.

1. Require company disclosure of human rights risks: Disclosures should include risks associated with their business as well as steps companies are taking to mitigate those risks.

2. Require human rights due diligence: Companies should be compelled to conduct risk assessments to identify potential human rights impacts and harms that could occur in relation to the use of the company’s platform, service, or device.

3. Require effective and accessible grievance and remedy mechanisms: These mechanisms should provide meaningful legal recourse and remedy for violations of freedom of expression and privacy.

4. Assess human rights risks of new legislation: All proposed laws that may affect freedom of expression and privacy should be subject to human rights impact assessments.

[28] “Governance advances and gaps,” 2018 Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index, rankingdigitalrights.org/index2018/report/inadequate-disclosure/#section-33

[29] Altschuller, Sarah A and Amy K Lehr, “The French Duty of Vigilance Law: What You Need to Know,” Corporate Social Responsibility and the Law, August 3, 2017, www.csrandthelaw.com/2017/08/03/the-french-duty-of-vigilance-law-what-you-need-to-know

[30] “Privacy,” Apple, accessed April 22, 2019, www.apple.com/lae/privacy

[31] “About Yandex,” Yandex, accessed April 22, 2019, yandex.com/company/general_info/yandex_today

[32] “Human Rights Policy,” (América Móvil, 2018), s22.q4cdn.com/604986553/files/doc_downloads/human_rights/Human-Rights-Policy.pdf and “2017 Sustainability Report,” (América Móvil, 2018), s22.q4cdn.com/604986553/files/doc_downloads/sustainability/sustainability-report-2017.pdf

[33]“A/HRC/29/32: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression” (United Nations Human Rights Council, May 22, 2015), ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/29/32

[34] See the 2019 RDR Index glossary at: rankingdigitalrights.org/2019-indicators/#hria

[35] See the 2019 RDR Index methodology at: rankingdigitalrights.org/index2019/indicators/g4

[36] Verena Fulde, “Deutsche Telekom’s guidelines for artificial intelligence,” Deutsche Telekom, accessed April 22, 2019, www.telekom.com/en/company/digital-responsibility/details/artificial-intelligence-ai-guideline-524366

[37] “G6: Remedy,” 2018 Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index, rankingdigitalrights.org/index2018/indicators/G6

[38] “National Action Plan,” Business & Human Rights Resource Center, accessed April 22, 2019, www.business-humanrights.org/en/un-guiding-principles/implementation-tools-examples/implementation-by-governments/by-type-of-initiative/national-action-plans

[39] Peter Micek, “New U.S. plan for responsible business conduct takes baby steps toward digital rights,” Access Now, January 30, 2017, www.accessnow.org/new-u-s-plan-responsible-business-conduct-takes-steps-toward-digital-rights

[40] “Non-financial reporting,” European Commission, accessed April 22, 2019, ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/non-financial-reporting_en

[41] “Companies failing to report meaningful information about their impacts on society and the environment,” Alliance for Corporate Transparency, February 8, 2019, www.allianceforcorporatetransparency.org/news/companies-failing.html

[42] Altschuller, Sarah A and Amy K Lehr, “The French Duty of Vigilance Law: What You Need to Know,” Corporate Social Responsibility and the Law, August 3, 2017, www.csrandthelaw.com/2017/08/03/the-french-duty-of-vigilance-law-what-you-need-to-know

[43] “German Development Ministry drafts law on mandatory human rights due diligence for German companies,” Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, accessed April 22, 2019, www.business-humanrights.org/en/german-development-ministry-drafts-law-on-mandatory-human-rights-due-diligence-for-german-companies

[44] Benjamin Fox, “Table human rights due diligence law, MEPs tell Commission,” Euractiv, March 28, 2019, www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/table-human-rights-due-diligence-law-meps-tell-commission

[45] “Investors representing $1.3 trillion voice support for legislation to mainstream ESG risk management in global financial systems,” Investor Alliance for Human Rights, March 25, 2019, investorsforhumanrights.org/news/investors-representing-13-trillion-voice-support-legislation-mainstream-esg-risk-management