29 Oct How are U.S. telcos playing the targeted advertising game?

Photo by Petr Kratochvil (CC0)

With rampant fears of digital disinformation about the U.S. presidential election and COVID-19 making the rounds, U.S. lawmakers from both parties are seeking to restrict the targeting of political ads online. Legislators like Anna Eshoo, Josh Hawley, and David Cicilline are pushing bills that would tackle ad targeting on platforms like Facebook and YouTube.

We know these and other companies’ algorithms feed users the most attention-getting content, even when it is misleading, hateful, or otherwise harmful to human rights—our spring 2020 report series, It’s the Business Model, looks at this in depth. But by focusing mainly on digital platforms, legislators let a very important player off the hook: U.S. telecommunications companies.

Telecommunications companies (telcos) like AT&T (ranked by RDR), Sprint, Comcast, and Verizon* offer customers different combinations of voice, text, broadband, and cable TV service. This means that they also have the ability to collect and combine customers’ data from multiple streams.

If I subscribe to a bundle of services from AT&T, the company can collect, combine, and correlate data from my internet browsing history, my TV-watching habits, and the infinite riches of my mobile phone activity and location data. On top of all this, AT&aT has my home address and billing information—valuable pieces of data that suggest a lot about what demographic groups I belong to.

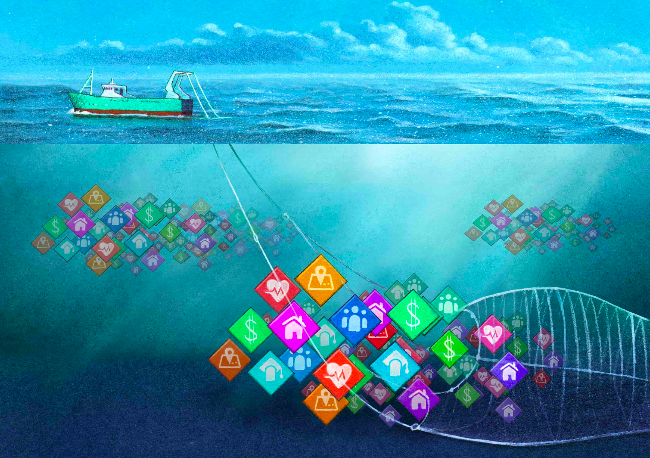

Telcos’ access to demographic data allows them to bring a unique level of precision to their calculations about customers’ interests. In the digital advertising world, this information doesn’t just benefit telcos—it can benefit a whole ecosystem of actors (including advertising companies, ad networks, and digital platforms themselves) who want to target specific groups of people with specific interests.

In the 2020 RDR Corporate Accountability Index (due out in February 2021), we will rank digital platforms and telcos on a new set of indicators measuring corporate policies and practices around targeted ads. We apply these indicators to every company we rank that engages in or enables any type of ad targeting, and to every company that shares or sells user data and insights to third parties for any type of advertising or sponsored content.

In our last post, we explained why we decided to apply these standards to both digital platforms and telcos. Here, we’ll get into some of the ways telcos are claiming a piece of the targeted advertising pie.

Selling ads on cable TV

Telcos have long used demographic data to entice advertisers. On cable TV, while television networks claim most of the advertising slots, providers (like Comcast) get a few minutes of ad time per hour as well. Since the 1980s, cable providers have been able to increase the price they charge advertisers for those meager slots by geographically targeting the ads by postal code.

Today, mirroring the techniques of digital platforms like Facebook and YouTube, some telcos are beginning to let advertisers target cable ads on a much more granular level. Telcos are taking into account what they know about each household, based on data they collect from people’s internet behavior, mobile activity, and TV-watching habits. Telcos then target ads accordingly. This means that even if my neighbor and I are both watching Trevor Noah’s show on Comedy Central, we may see different ads during the commercial breaks.

Cable companies Comcast, Charter, and Cox have a partnership called Ampersand under which they synthesize user data in order to target TV ads. They added significant new ad-targeting capabilities—including letting advertisers target on the level of individual households instead of zip code—in time for the ad spending period leading up to the presidential election. For viewers, new systems like this are making the cable TV ad experience feel closer to what happens online. We’re seeing fewer ads for things we’d never buy, but having more of that uncanny feeling of being followed by advertisers who seem to know a lot about our interests.

While there are stronger transparency requirements for ads on television, targeted advertising on cable still could exacerbate the same problems that it has inflamed on social media: misinformation, polarization, and further fracturing of the public sphere.

Selling demographic data for the online targeted-advertising ecosystem

Telcos also sell user data to other players in the targeted-ad market when this proves more profitable than simply using it in-house. While some telcos sell user data outright (as T-Mobile, Sprint, and AT&T were caught doing with location data in the U.S.) others, like Verizon, sell “insights” based on user data. The “first party data” in telcos’ coffers can include mobile users’ location data and internet browsing history.

However, for online advertisers, the most important data from telcos is often their mundane but exceptionally accurate demographic data.

Precise demographic data, such as postal code and income level, adds an incredibly potent ingredient to the digital profiles that are used to target consumers, and can thus compound the very real problems that targeted advertising creates. While advertising companies may be able to target a political ad at certain users based on their online behaviors, they can do this much more precisely when they have users’ demographic data on hand.

Online advertisers and digital platforms often cannot directly access accurate and precise demographic data about users. This means that telcos are providing the industry with the much-needed “truth set” that demographic data represents. When combined with other data collected from data brokers and internet companies surveilling users’ online behavior, the “truth set” provided by telcos can anchor and enhance the value of data collected and inferred by these other actors. As such, telcos are helping online platforms increase their already unprecedented concentration of information and the power that comes with it.

To give an example, I live in a densely populated area of Washington, D.C. Before COVID came along, I either rode my bike or took the Metro to work every day. My mobile provider, AT&T, could probably glean these patterns by combining my location data (which would reveal my frequent Metro rides), my browsing behavior (indicative of my age and interests, like bike-riding), and my address. This would explain why, on the web, I’m less likely to see car ads, and more likely to see ads for Lyft or a local bikeshare. Most TV-based ads are still targeted nationally, by zip code. But when telcos can’t do the targeting themselves, they are more than happy to sell user data to the online advertisers who can take the final leap to targeting specific individuals as they browse the web.

It doesn’t end there. Many telcos also plug their data into parts of the internet-based targeted advertising “stack,” as AT&T has done with its Xandr advertising subsidiary. But, as our research has shown, telcos are hesitant to clearly describe these activities to the public, making it difficult to hold them accountable for these practices.

In European Union countries, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides some privacy protection not just against Google and Facebook’s use of data, but against that of telcos as well. But the United States is still struggling to pass such a law.

Convergence…towards what?

This correlation of personal data collected by telcos and digital advertising companies as customers use different services leads to what people in advertising call “convergence”—the ability of an advertiser to use all these data streams to capture audiences “across screens.”

The involvement of telcos is a key driver of this convergence because it brings otherwise inaccessible demographic data streams into the targeted-ad world. When it comes to political campaigns, these systems can enable candidates to ensure that voters see the same messages—misleading and hateful ones included—on every device they own, no matter what services they are using.

We’ve begun evaluating telecommunications’ companies targeted-advertising policies because we worry that the targeted-ad practices of telcos are no less harmful than those used by digital platforms like Google and Facebook.

As the movement to constrain targeted advertising gains momentum, advocates must look more critically at the role that telcos play in this milieu. Wherever it emerges, it is the targeting-advertising business model, more than anything inherent about social media in particular, that is driving many of the problems in our public sphere and that could undermine the integrity of next week’s elections in the U.S.

*Ranking Digital Rights evaluates Verizon Media, which owns Yahoo! Mail and Tumblr. We do not evaluate Verizon’s telecommunications services.