Over the past decade, Ranking Digital Rights has established a strong reputation for holding Big Tech and Telco Giant companies accountable for upholding human rights. Many bright minds have passed through RDR’s (figurative) doors, who have made important contributions to ensuring RDR would find the best way possible to push these companies to be transparent about their digital rights policies. All of this hard work has been reflected in the development, and evolution, of the RDR methodology, which allows us to accurately and effectively track company commitments and disclosures of policies meant to protect our most critical digital rights. This is the story of how the RDR standards came to be a decade ago, and how they’ve evolved since to best examine and reflect company policies, and the changes needed to protect our rights online.

Part 1: Where It All Started

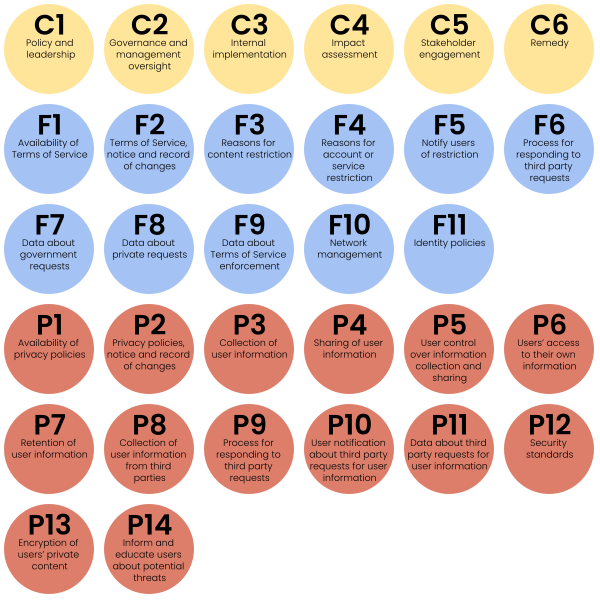

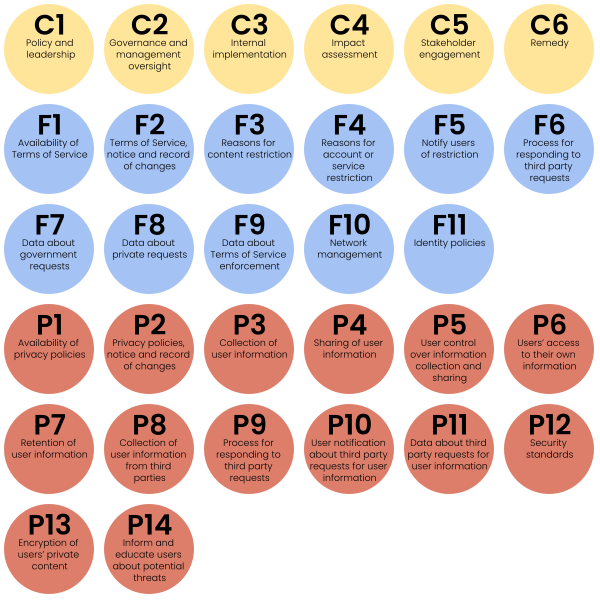

2015 RDR Standards Indicators Overview

2015 RDR Standards Indicators Overview

In 2013, after the launch of her critical book Consent of the Networked, RDR was founded by author and internet freedom activist Rebecca MacKinnon. The book was a powerful call to action, a way to shed light on how the convergence of unchecked government actions and unaccountable company practices were threatening the future of democracy and human rights globally. As a response to a dearth of existing research on these trends, MacKinnon proposed a project which would rank companies and educate stakeholders with three main goals in mind: examining corporate policy; identifying which companies could be considered industry “leaders,” if any, on digital rights, and which ones needed to catch up; and, finally, setting a roadmap for all companies to improve their policies and practices through concrete, measurable steps. Over time, our standards have changed to reflect both growing knowledge of how best to accurately capture disclosed company behavior as well as to account for the ever-evolving tech industry; moving forward, RDR’s methodology will continue to do so.

To produce a first iteration of RDR’s draft criteria, Rebecca launched a research and consultation process through a collaborative partnership with the University of Pennsylvania. It took two years after RDR first came into being before the launch of the first official RDR standards in 2015. These draft criterias identified three key issue areas, which became the three main pillars of RDR’s standards: The first revolves around the broad responsibility of businesses in the context of well-established international human rights standards. The remaining two focus specifically on businesses’ responsibilities toward two fundamental rights: the right to freedom of expression and information and the right to privacy.

In the earliest edition of the standards, the first of the three categories was known as “Commitment.” (This would later become “Governance” from 2017 on, while Freedom of Expression (F) and Privacy (P) have retained their names.) But it isn’t only the names that distinguish the 2015 methodology from today’s RDR standards. This first version of the standards featured far fewer indicators. This also meant fewer of what we refer to as “elements” (a series of questions that help score each indicator), which also didn’t yet include a harmonized answers format. Some indicators, like C4, had a checklist for evaluation, meaning that a full credit is earned when all listed elements are checked off. Other indicators, like C1, had questions with yes/no answers, or with other pre-selected answers. A full explanation of the methodology can be found here.

Using this methodology, in November 2015, RDR launched its first official Corporate Accountability Index, evaluating eight tech companies and eight telcos. The scorecard received worldwide media attention, demonstrating global interest in corporate respect for users’ rights and the relevance of RDR’s work in ongoing discussions around digital rights issues.

Part 2: RDR Standards Evolve Toward Their Current Iteration

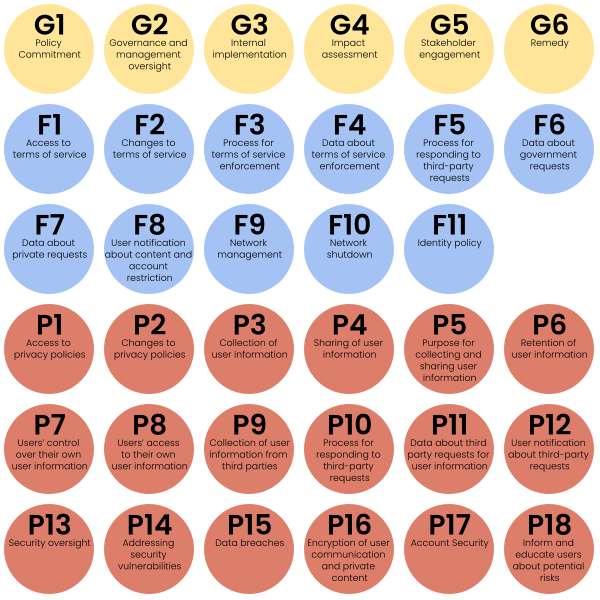

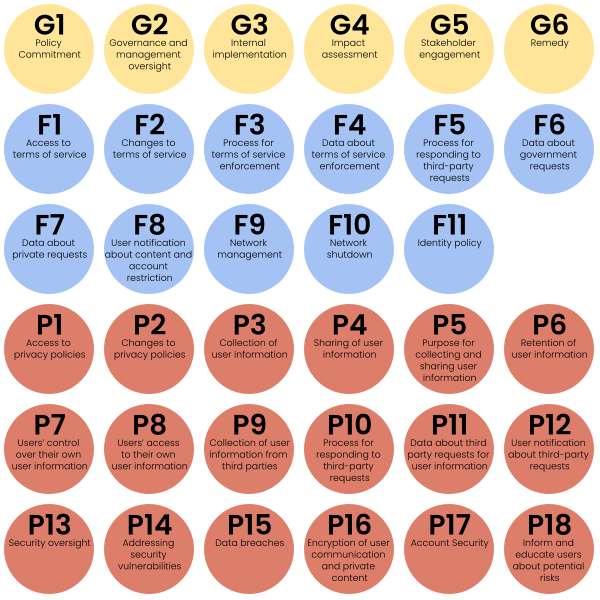

2017 RDR Standards Indicators Overview

2017 RDR Standards Indicators Overview

Having survived the production and release of the inaugural Index, the team did not rest on its laurels but went right back to work revising the methodology and data collection process based on what we had learned through this experience. In July 2016, a draft revision (edited version) was published for public consultation. Stakeholders from civil society, academia, the investor community, and the companies themselves provided feedback. The RDR team then incorporated this feedback, received across two phases of consultations, in order to create a finalized 2017 RDR Index methodology.

Some substantial changes were made to this new version. It was at this point that the “Commitment” category was changed to “Governance,” in order to more accurately reflect that these indicators and their elements go beyond seeking a mere commitment. They ask for companies to demonstrate broad governance and oversight mechanisms to ensure they are able to fulfill their commitments to freedom of expression and privacy. The indicators under the “Freedom of Expression” category were expanded and reordered. For example, an indicator about network shutdowns was created in order to better capture how companies were dealing with what RDR noticed was a growing threat to freedom of expression. Indicators in the “Privacy” section were also reorganized and reframed. In addition, an indicator on data breaches was added, while several indicators related to security standards were revised.

All indicators were refined to use a standardized scoring format, making the process of data collection and scores calculation more straightforward. As we detailed at the time, the indicators were reworked so that they were framed as normative statements (“The company should…”), while elements became questions (“Does the company…?”). This meant that the indicators stated our expected standards more explicitly, while the elements measured whether companies meet those standards:

- Full disclosure = 100

- Partial = 50

- No disclosure found = 0

- No = 0

- N/A

Additional research and analysis in 2016 concluded that, given that people around the world access the Internet primarily, or even exclusively, through smartphones, the Index should include companies that produce mobile software and devices. As a result, mobile ecosystem services were added, which also meant the addition of companies like Apple and Samsung that primarily manufacture devices and hardware. With these changes complete, a new Corporate Accountability Index was launched in March 2017, evaluating 22 companies using 35 indicators.

For the next scorecard, launched in April 2018, the standards remained the same. In 2019, some minor changes were made to two indicators, but not enough to speak of a wholly “new” iteration of the standards.

Part 3: RDR Takes On the Business Model

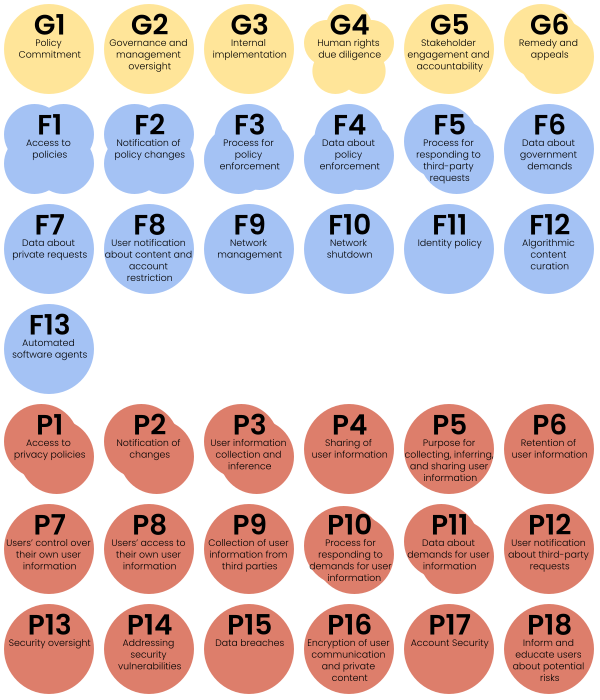

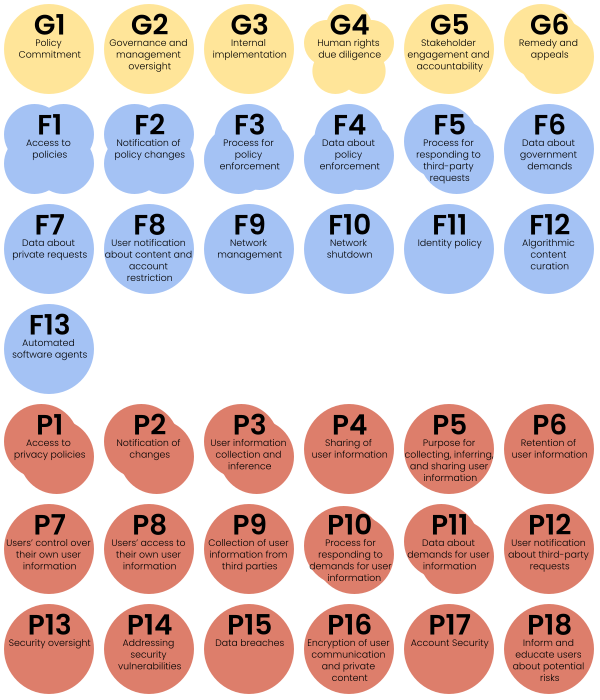

2020 RDR Standards Overview (indicator families have different shapes based on their number of sub-indicators)

2020 RDR Standards Overview (indicator families have different shapes based on their number of sub-indicators)

In 2019, big changes were afoot once again, as Ranking Digital Rights began to hone in on a crucial missing element in the web of complex power dynamics between government and Big Tech that was wreaking havoc on our information ecosystems. It had become clear that the problems caused by Big Tech did not stem solely from what might amount to improper security or company negligence. Instead, companies’ very deliberate use of surveillance-based business models was directly threatening democracies and users’ rights. One year later, RDR launched the “It’s The Business Model” report series, as well as a new and revised version of the RDR standards. This new iteration included indicators meant to hold companies accountable on two key issues directly related to this business model: targeted advertising and algorithmic content governance systems.

During the first half of 2019, RDR research staff conducted extensive desk research and gathered feedback from more than 90 expert stakeholders. During this process, a consensus was reached around the functioning of the surveillance-industry business model. As a result, in October 2019, RDR published draft indicators on both targeted advertising and algorithmic systems.

RDR published a draft version of the 2020 RDR Index methodology (redline version) in April of that year, which integrated work across the three main categories. This draft was validated by a final round of public consultation, resulting in the final 2020 RDR standards. One of the main challenges of this round of additions was the sheer volume of new indicators that were being added. The number of evaluation criterias evolved from 35 indicators in 2019 to 58 in 2020.

This 58% increase could easily have made it impossible to conduct year-on-year comparisons of how company policies had improved or worsened. But the team came up with a solution: introducing “families” of indicators, groups of indicators that apply to similar issue areas. For example, the G6 indicator—which evaluates whether companies provide clear and predictable remedy when users feel their rights has been violated—was divided out into a family of two indicators: G6a is the same as indicator G6 from the 2019 RDR Index, while G6b is a new indicator that applies standards for how platforms should handle content moderation appeals. This approach made it possible to integrate new indicators addressing company targeted advertising and algorithmic systems without having to renumber existing indicators, and thus imperil our ability to continue making comparisons through time.

Part 4: Facing New and Old Challenges—RDR’s Methodology Today

The final important change came in 2022, this time focused on the way RDR’s results were presented. For the first time, the Index was launched in two parts: The Big Tech Scorecard and the Telco Giants Scorecard, using the same standards as in 2020. RDR was motivated both by external feedback that the 26-company Index was too dense for the audiences to engage with all at once, and by the significant resource challenges involved in producing a report of this scope every year. Splitting the Index into two Scorecards allowed RDR to design a more manageable process for data collection and analysis, and to be more thoughtful about how results were presented about these two important and different sectors.

Today, the RDR methodology is facing new challenges, as well as some unresolved ones from its past. It’s always been hard to measure something as complex as corporate commitments to digital rights, and as a result, the RDR standards are not easy to quickly grasp. The organic evolution of the indicators, as described above, means a large number of indicators that have been added over time, which can be hard to digest, particularly since the way in which companies’ final scores are calculated is not always intuitive. And a total of 58 different criterias means a pronounced learning curve for researchers using the standards for the first time.

Finally, it’s important to note that this methodology has not only been used throughout the years by the team itself; RDR’s research process has always been open source, and its standards have remained available to be adopted by other organizations and experts. This transparency in the development of these standards made it possible for global digital rights organizations to begin creating the first adaptations of the RDR methodology in Pakistan, India, Kenya, Senegal, and the Arab States, beginning in 2016 through 2018.

In the years since, RDR has continued working closely with research and advocacy partners globally who wish to employ the open RDR Index methodology to add to the growing number of adaptations. In 2021, RDR began a collaboration with the Greater Internet Freedom Project (GIF) at Internews to mentor and help regional and local partners by transferring technical expertise to hold tech and telecom companies accountable for protecting internet freedom. As a result of this and other collaborations, more than 200 companies have been evaluated using the RDR standards across 46 countries. Though this global work has brought great rewards and reams of new data, it is not without its unique challenges.

Some partners have noted that certain indicators are less relevant for smaller companies than for those large giants evaluated by the flagship RDR indexes. For example, small- and medium-sized companies that are not traded on a public stock exchange may not have a Board of Directors or other governance structures that are central to the G indicators. Thus, RDR is continuing to work to find the right balance between simple and well-defined standards, which are easy to understand, and ensuring sufficient flexibility to adapt to different local contexts.

Another challenge RDR currently faces: determining how all the additional information and data being created by an increasing number of local partners can then be used for meta comparison and analysis, particularly when they must often modify the methodology to carry out their individual research projects. One of the key findings of the latest TGS was a seemingly consistent disconnect between the policies observed at company headquarters compared to those of their various subsidiaries, which were, in many instances, in countries with a more volatile environment for human rights. There’s still more work to do to analyze this data from partners and paint a clearer picture of any notable pattern of discrepancies.

Part 5: Conclusion—RDR Looks to the Future

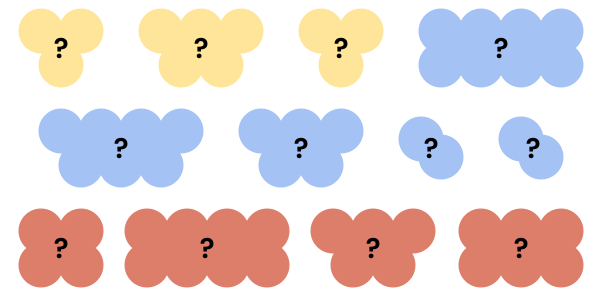

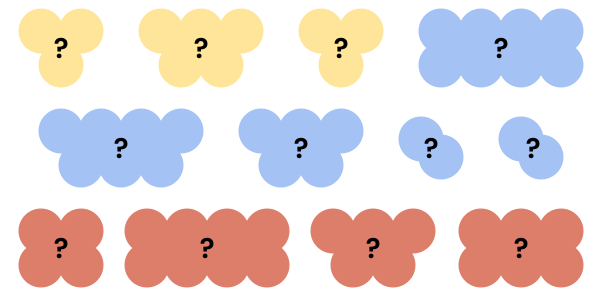

A new iteration of RDR standards is coming, stay tuned!

A new iteration of RDR standards is coming, stay tuned!

As RDR moves into its second decade, it’s important that its standards serve not only the needs of the core team itself and its flagship indexes. RDR hopes that its work can enrich the field of corporate accountability in the tech sector as a whole, creating a space where other organizations bloom, including in the Majority World.

Finally, RDR has always recognized the constantly evolving nature of the tech field. As a consequence, human rights are affected in the digital sphere in new ways, making revisions of the standards necessary to acknowledge these new challenges. The growing and novel uses of generative AI is one of the biggest and most imposing challenges our field has faced in a long time. As such, RDR is developing a set of preliminary standards for generative AI, which presents many potential new risks, especially given the unprecedented speed at which it’s being rolled out and adopted by almost all tech companies. A new Generative AI Accountability Scorecard, measuring generative AI services is forthcoming. We currently have an ongoing call for consultations on our generative AI standards, which will remain open until September 10.

Meanwhile, the RDR team is working on a new, broader revision of its methodology that will take into account all of these challenges. With the future of tech accountability facing perhaps more uncertainties than ever, this won’t be an easy endeavor. But there are also many exciting, positive updates in store for the next generation of RDR standards, particularly as our global work continues to expand. And, as always, the entirety of our upcoming development process will be open and collective. This means that all of our allies and stakeholders will be able to follow along on this next chapter in the ever–changing story of the RDR methodology.

Acknowledgements: This article was written by Augusto Mathurin with contributions from Sophia Crabbe-Field and Nathalie Maréchal.

2015 RDR Standards Indicators Overview

2015 RDR Standards Indicators Overview 2017 RDR Standards Indicators Overview

2017 RDR Standards Indicators Overview 2020 RDR Standards Overview (indicator families have different shapes based on their number of sub-indicators)

2020 RDR Standards Overview (indicator families have different shapes based on their number of sub-indicators) A new iteration of RDR standards is coming, stay tuned!

A new iteration of RDR standards is coming, stay tuned!