08 Dec Who has the power? The Party, the public, and Big Tech in China

When the government of China put out a draft regulation on algorithms in August, it broke ground at a global scale. The draft laid out rules and standards for tech platform recommendation algorithms like no other government has. And it surprised some, especially Western onlookers, by introducing a handful of reasonable protections for users’ rights and interests.

The draft requires companies to be more transparent about their algorithmic systems and to allow users to opt out of such systems. It addresses tech platform addiction and it seeks some protections for people working in the platform-based gig economy (such as delivery workers). It also compels tech platforms to enforce “mainstream” (i.e., Chinese Communist Party) values.

People who have been watching the evolution of China’s tech policy regime in recent years saw the draft as a reflection of the major interests that the Chinese government and Communist Party have been working to balance: tech power on one hand, and public pressure on the other.

China is notorious for its digital censorship and public surveillance systems. But the state is not the only entity that poses a threat to Chinese people’s human rights. Until recently, Chinese tech companies were both enabling state efforts to control information and surveil the public, and reaping handsome profits by collecting and monetizing people’s data. Over the past decade, just like their Silicon Valley counterparts, China’s tech giants have abused user data, ignored market regulation, and deployed exploitative recommendation systems. And people have noticed. Public frustration about these practices and their effects on society reached a fever pitch in 2020 when China saw a spike in fatal traffic accidents resulting from food delivery workers trying desperately to keep up with the algorithmically-generated delivery times issued by their tech platform employers.

Public harms like these don’t just reflect poorly on big tech companies. They lay bare the lack of control that the government has over such corporations. And they pose a threat to the predominant position of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Chinese society.

In order to assert authority over these companies, and to maintain or even improve their image as entities that serve and protect the public, the CCP (which makes key decisions about China’s policy environment) and the government (which implements those decisions) have pushed through a raft of tech-focused regulations in recent years—the Cybercrime Law, the Personal Information Protection Law, and the Data Security Law—that seek to rein in companies’ data collection and monetization powers and, in some cases, to actually improve protections for the public.

These laws complicate narratives among media and policymakers in the West, who often portray China’s tech companies either as agents spreading Communist ideology and spying globally at the behest of Beijing, or as beacons of capitalism victimized by the Party’s relentless crackdowns that aim to show “who is the real boss.” There is some truth in each of these portrayals, but both fail to acknowledge the importance and rights of Chinese people. These lines of thinking also fail to account for the populist stance of the state.

Caught between the massive powers of the government on one hand, and tech companies on the other, Chinese users and their interests often get squeezed into a position where they have little sway. However, the three groups—the party, the public, and the tech powers—are intertwined and do interact with each other in a dynamic (if sometimes shifting) equilibrium.

This essay explores some critical questions about this dynamic: What is the real reason for the Chinese government’s regulatory crackdowns on tech companies? To what extent is the state trying to placate public complaints about tech giants? And most importantly: How do these things affect millions of users’ interests and rights?

Are these new laws really benefiting users?

Western media often focus on how China’s changing regulatory environment affects the operations and business models of Chinese tech companies, but leave users’ rights out of the picture. At Ranking Digital Rights, we put users’ rights at the center of our research. Over time, our evaluations of three of China’s leading tech giants—Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent—have shown how China’s regulatory environment has brought some benefits for people’s rights to privacy and security, as well as control over their information, albeit only in areas unrelated to Chinese government surveillance.

China’s regulation of user data collection has undergone a sea change since the adoption of the 2017 Cybersecurity Law, which focused on security and cybercrime protections and established principles of “legality, propriety, and necessity” in user information collection. It was followed by the September 2021 Data Security Law, an effort to protect critical information infrastructure, and then by the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which went into force on November 1. A sweeping data privacy law, PIPL defines personal information and sensitive information, compels data processors to obtain users’ consent prior to collecting their data, and requires that companies allow users to opt out of targeted ads. It also put a ban on automated decision-making that can cause price discrimination.

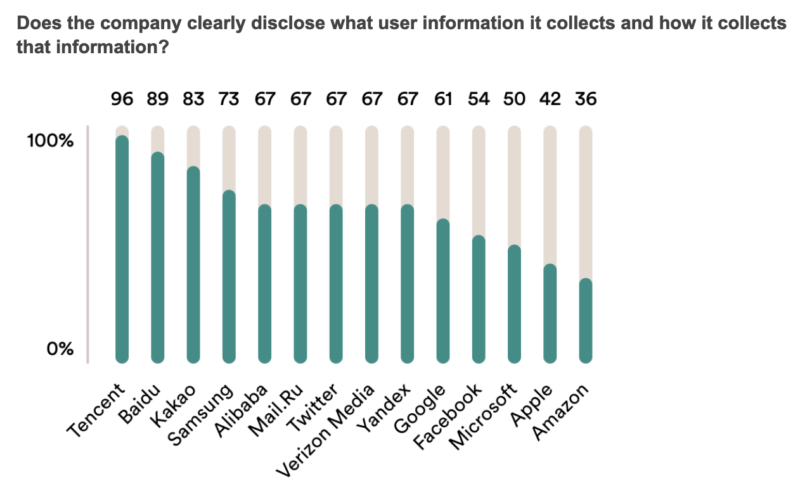

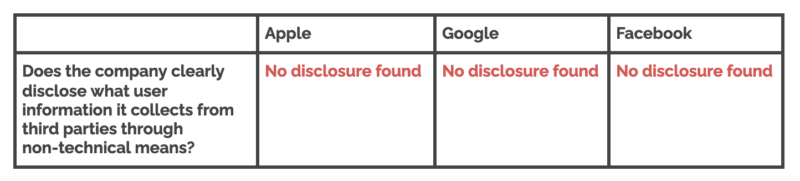

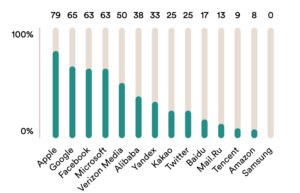

These laws do appear to have brought increased protections for users wanting more control over how tech platforms use and profit from their data. When we reviewed Chinese companies’ policies alongside those of 11 other globally dominant digital platforms, Baidu and Tencent were more transparent about how they collect user information than all the other platforms we rank, including Google, Apple, and Microsoft. Both Baidu and Tencent made explicit commitments to purpose limitation, vowing only to collect data that was needed to perform a given service. Alibaba fell behind major Korean companies Kakao and Samsung, but still outranked all the major U.S. platforms. In our July 2021 evaluation of ByteDance (parent company of TikTok), we found that Douyin (TikTok’s Chinese counterpart) far outpaced TikTok on these metrics, by committing to only collecting necessary information for the service.

Both Baidu and Tencent also have improved their privacy policy portals, making it easier for users to access privacy policies for various products in one place.

We also found that all three companies provided much more information about their contingency plans to handle data breaches than they had in the past, and more than other companies across the board. This change was likely inspired by the Cybersecurity Law, which requires companies to plan for potential data breaches.

Smaller improvements have emerged as well. On Alibaba’s Taobao, users can opt out of recommendations with a single click. The same is true for targeted ads. These and other updates give the impression that the platforms want to protect the rights of users and stand with the government at the same time.

The drawbacks

It may seem like a happy ending to the story. China’s regulatory environment is clearly more privacy-protective than it was in the past, even as state surveillance practices continue unabated. But even though China’s tech companies have made the right changes to their policies, there’s strong evidence that many of them are not following their own rules.

Tencent and ByteDance have been plagued with scandals and denounced by Beijing for violating the “necessity” rule laid out in the Cybersecurity Law. In May this year, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the country’s top internet regulator, publicly identified 105 popular apps that had illicitly collected user information and failed to provide options for users to delete or correct personal information. These apps included Baidu Browser and Baidu App, a “super app” interface for finding news, pictures, videos, and other content on mobile. Soon thereafter, Tencent’s mobile phone security app, which is meant to protect the privacy and security of users’ phones, was disciplined by the CAC for collecting “personal information irrelevant to the service it provides,” despite the promises in its policies. Douyin was caught “collecting personal information irrelevant to its service,” despite the fact that its privacy policy states that it only collects user information “necessary” to realize functions and services.

In June 2021, digital news aggregator apps, including Today’s Headline (operated by ByteDance), Tencent News, and Sina News, were publicly rebuked by the CAC for collecting user information irrelevant to the service, collecting user information without user permission, or both.

In August, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) publicly declared that Tencent’s WeChat (China’s most popular app) had used “contact list and geolocation information illegally.”

Anecdotally, Chinese users have voiced concerns that mobile apps are eavesdropping on their daily conversations, sometimes even when the microphone function is turned off. These accusations have implicated apps ranging from food delivery platforms, to Tencent’s WeChat, to Alibaba’s Taobao. Though it’s hard to find solid evidence, technical tests show that such snooping practices are feasible. Some users shared their experiences under the relevant topics on Zhihu, a Quorum-like platform in China. Ironically, that platform too was accused of eavesdropping on users’ private conversations.

The latest public condemnation from the Chinese government was announced in November. MIIT ordered 38 apps, including two apps run by Tencent, Tencent news and QQ Music, to stop “collecting user information excessively.” Soon after, the Ministry ordered Tencent to submit any new updates of its apps for technical testing and approval to ensure they meet national privacy standards. The company’s apps have been publicly accused of illegally collecting user information by MIIT four times in 2021.

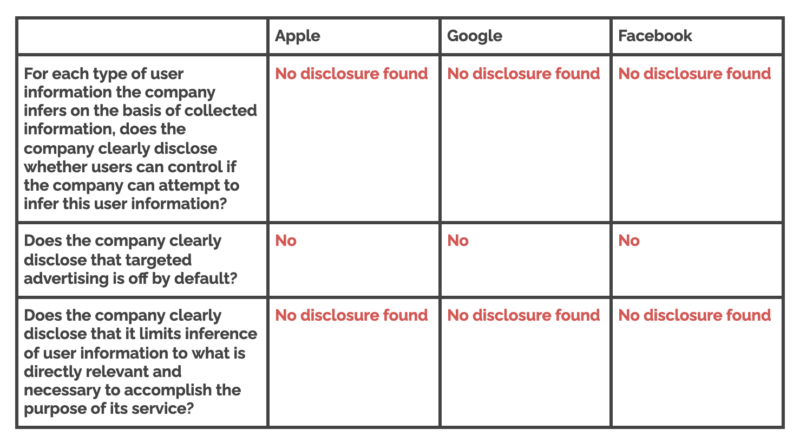

Although the Personal Information Protection Law requires tech companies to allow users to opt out of targeted advertising, the companies have turned this into a battle of wits. Baidu technically allows users to do this, but the company’s privacy policy does not include any information on where or how to actually opt out. While PIPL was still pending, both Alibaba and Tencent maintained options for users to turn off ad targeting (which is on by default), but made the selection time-limited, so that users would be reverted back to the default after six months. Tencent did not cancel the time limit until October 29, when the company was sued in a court of Shenzhen City (where Tencent is headquartered) for infringing user rights. The lawsuit included accusations regarding the time limit on opt-outs for ad targeting. Taobao updated its privacy policy and the setting requirement in a hurry on November 1, the day PIPL took effect.

The draft regulation on algorithms and the voices of Chinese users

As it is still at the drafting stage, we don’t yet know what will appear in the final text of China’s regulation on algorithms. But the draft has one very specific provision that appears to be a direct response to public concern. It requires labor platforms (such as food delivery services) to improve their job distribution, payment, rewards, and punishment systems to protect the rights of contract laborers.

In 2020, Chinese media outlet Renwu reported on how the algorithmic systems powering China’s largest food delivery platforms, including Ele.me (owned by Alibaba) and Meituan (backed by Tencent), were exploiting delivery workers and all but forcing them to violate traffic laws. To keep up with the apps’ algorithmically optimized delivery times, workers were exceeding speed limits, running stop lights, and endangering people’s lives. In August 2020 alone, the traffic police of Shenzhen City recorded 12,000 traffic violations related to delivery workers riding mopeds or converted bicycles. Shanghai City data showed that traffic accidents involving delivery workers caused five deaths and 324 injuries in the first half of 2019. The Renwu story (available here in English) resonated with people’s daily experience in the street immediately, eliciting tens of thousands of comments.

The public response could not be ignored. Although civilians are rarely able to influence or shape legislation in China, public safety has become an area in which they do have some sway. The Communist Party, though powerful, needs to respond to public complaints and tie this to its efforts to regulate tech companies. An important part of the Party’s legitimacy comes from the notion that it is “serving the people.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping has emphasized this point in recent statements for state media: “The development of the internet and information industry must implement the people-centered idea of development and take the improvement of people’s well-being as the starting point and foothold of informatization, to enable people to acquire more sense of contentment, happiness, and safety.”

Although the draft regulation on algorithms covers a much broader range of issues than just worker rights and safety, it suggests that public pressure can play a role in policymaking in China, when certain conditions intersect.

The future of Chinese users’ rights

In another kind of society, direct pressure and input from civil society organizations and academic experts could help keep pressure on tech companies, hold them accountable to the public, and create an environment where both government and corporate actors would better protect users’ rights. But in China, companies are primarily accountable to Beijing, not to users. It is only in instances where public concern aligns with state interests—most commonly, when the state can appear as “protector” of the people—that public pressure seems to come into play.

Even with new regulations, we can expect China’s tech giants to remain very profitable. The Chinese government’s various new and forthcoming tech-focused laws are intended to curb, but not drastically reduce, corporate power. They constitute a strategic and occasional application of pressure to assert state and Party power, and bring certain benefits to the government. This fits with the government’s long-standing mission to prioritize “healthy and orderly development,” a phrase that appears in countless industry guidelines and policies.

Will Beijing’s campaign to rein in China’s big tech companies persist? Law enforcement campaigns are not easy or cheap. At some stage, as other pressing issues arise, we can expect this agenda item to move lower down on the Party’s priority list, at which point tech companies may be even less inclined to honor their promises.