12 Jun Arab region’s telecommunications companies fail to respect users’ digital rights

United Arab Emirates-based Etisalat and Qatar-based Ooredoo once again ranked lowest among telecommunications companies in the Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index — and were among the few companies to score even lower than in previous years. This downward trend coincides with steady declines in internet freedom in both countries and across the Arab region, where internet users face increasing government censorship and surveillance.

Internet service providers in the Arab region operate in one of the world’s more restrictive environments. Authorities have increasingly cracked down on online expression, particularly in the wake of the Arab Spring in 2011 when the internet proved to be a powerful tool for human rights advocates. Rights groups and experts have since reported steady declines in internet freedom in a number of countries across the region — including in Bahrain, Egypt, Libya, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Qatar — as governments have enacted draconian measures criminalizing online speech, engaged in targeted surveillance of human rights activists, journalists, and political opponents, and shut down access to select services or to the entire internet.

It is perhaps not surprising then that Etisalat (based in the UAE) and Ooredoo(based in Qatar) continued to be the two lowest scoring telecommunications companies in the RDR Index. The RDR Index evaluates how transparent companies are about their policies and practices affecting human rights — specifically users’ freedom of expression and privacy. We evaluated Etisalat and Ooredoo on their disclosed policies in their home markets, where UAE and Qatari governments actively restrict freedom of expression online and have a monopoly over private telecommunications markets.

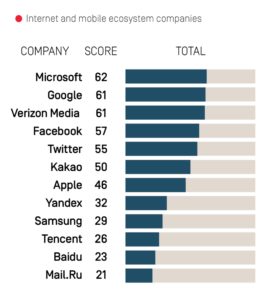

The 2019 RDR Index ranked 12 telecommunications companies and 12 internet and mobile ecosystem companies on how transparent they are about commitments, policies, and practices affecting freedom of expression and privacy. Read about the RDR Index methodology, indicators, and research process.

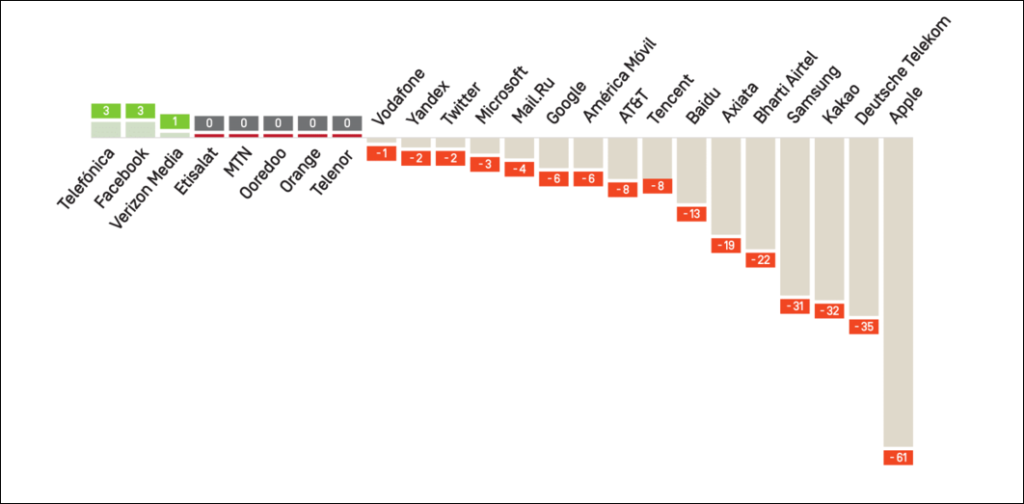

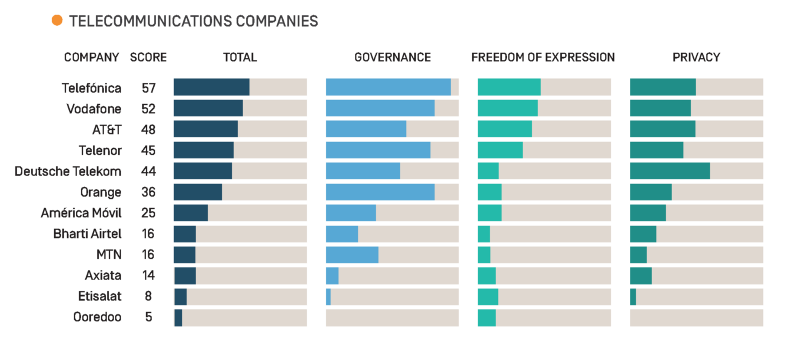

What is surprising, however, is just how little progress these companies have made. While a majority of companies evaluated in the 2019 RDR Index made some improvements — including companies operating in equally restrictive countries like China and Russia — Ooredoo and Etisalat were among the few companies to actually backslide in this year’s ranking, disclosing even lessabout key policies and practices affecting users’ rights than previously. Neither company even so much as published a privacy policy — although there are no laws preventing either company from doing so.

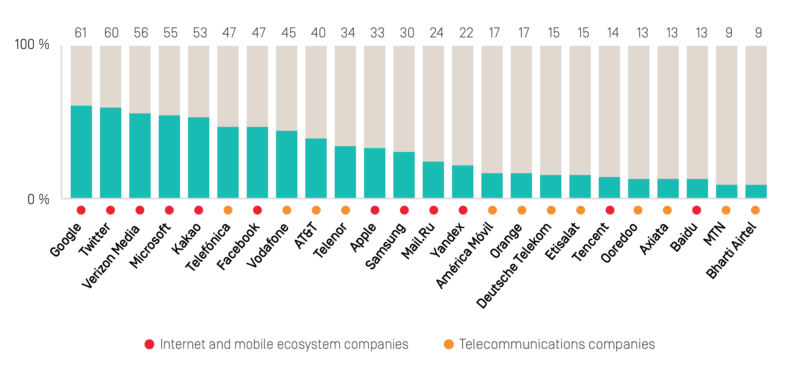

Comparative year-on-year scores (2018 RDR Index v. 2019 RDR Index). Most companies evaluated improved their overall score in the 2019 RDR Index. Etisalat and Ooredoo were among just three companies whose scores declined, both for disclosing even less about policies affecting freedom expression than previously.

These results highlight growing concerns by digital rights advocates about the deterioration of internet freedom across the Arab region, where internet service providers — which are often state-owned and state-controlled — have become a de facto part of the state’s censorship and surveillance apparatus. Results also spotlight how internet users in the region are deprived of even the most basic information about how and why content is censored, what information companies collect and share about them and with whom — including with governments and law enforcement — and what companies do to keep that information secure.

Government owned, government controlled

While the UAE and Qatar have some of the best-connected internet systems in the Arab region, online speech in both countries is heavily censored. Along with legal measures, authorities control the internet through direct ownership: the UAE government owns a 60 percent stake in Etisalat and the Qatari government has a 69 percent stake in the Ooredoo Group.

Although censorship is generally more pervasive in the UAE than in Qatar, internet filtering is prevalent in both countries, as internet service providers (ISPs) in both the UAE and Qatar are required to block access to content deemed objectionable by authorities, including political speech and websites of media outlets and human rights organizations.

In 2016, Qatar’s only two ISPs, Ooredoo and Vodafone, blocked access to independent media site Doha News, without providing an explanation to its publishers or users. In the UAE, severe cybercrime laws paired with expansive government surveillance have resulted in the widespread silencing of both individuals and organizations. In 2017, authorities in the UAE blocked a number of Qatari media sites, including Al-Jazeera Live and Huffington Post Arabic, as part of a political strategy to isolate Qatar in the region. Content deemed offensive or critical of the government can result in hefty prison sentences, including up to 15 years for expressing sympathy for Qatar.

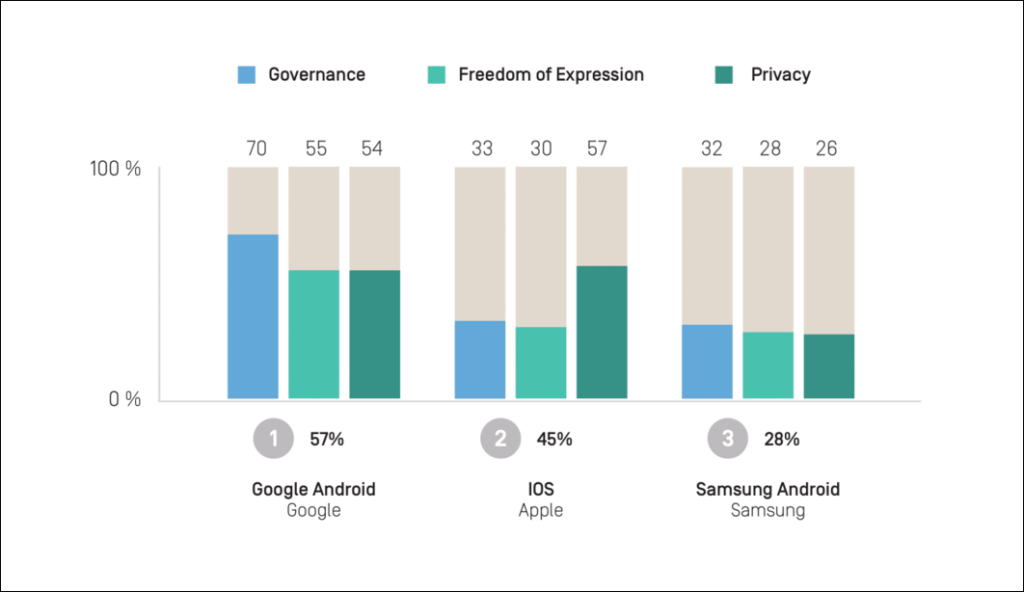

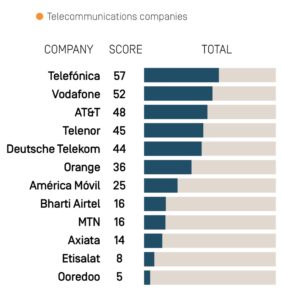

The 2019 RDR Index found that both Etisalat and Ooredoo revealed hardly anything at all about their policies and practices affecting users’ freedom of expression, receiving some of the lowest scores in this category among all companies evaluated. Both even lost points in the freedom of expression category this year: Etisalat revealed less information about its processes for responding to third-party requests to restrict content and Ooredoo made its terms of service less accessible to users than it had previously.

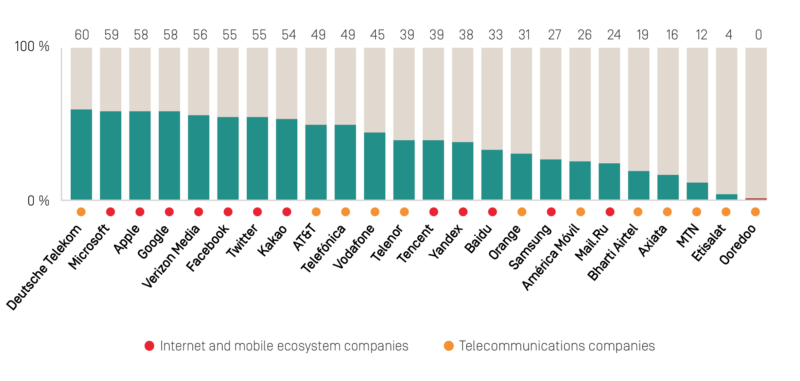

Freedom of expression scores: 2019 RDR Index. The Freedom of expression category of the RDR Index applies 11 indicators evaluating how transparent companies are about their rules and how they are enforced, how they deal with government demands to block, filter, or otherwise censor content, and how they respond to government orders to shut down access to the internet.

Notably, neither company disclosed anything about how they respond to government demands to filter or block content or what actions they have taken in response to these demands. While it is a criminal offense in the UAE not to comply with government blocking orders, there is no law prohibiting Etisalat from disclosing how it handles these requests or its compliance rates with either government or private content-blocking requests. Similarly, telecommunications companies in Qatar are legally required to comply with judicial orders to block content, but there is no law prohibiting these companies from disclosing their processes for handling such demands or from publishing its compliance rates with either government or private content-blocking requests.

In addition, both Etisalat and Ooredoo failed to disclose sufficient information about how they respond to government demands to shut down access to the internet or to specific services or applications — an issue of particular relevance in both the UAE and Qatar, where access to certain voice and video services and applications is restricted. In the UAE, for instance, these applications have been banned under a 2009 regulation that allows only licensed telecommunications providers to offer such services. Despite the ban, users were able to make audio and video calls via Skype until access to that service was blocked in December 2017.

Privacy blackout

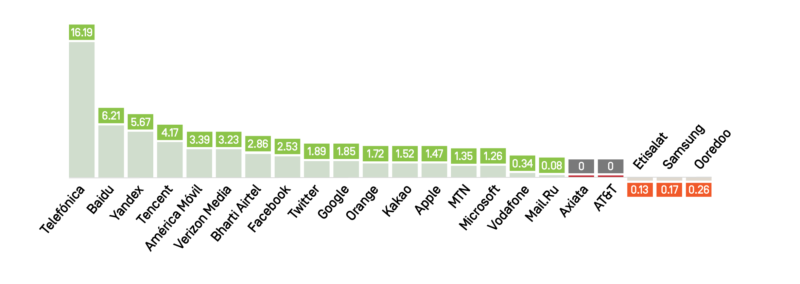

Nearly every ranked company improved their privacy score in the 2019 RDR Index — a trend driven in part by both new data protection regulations in the European Union and elsewhere, as well as by public demand for greater transparency and accountability. Even Chinese internet companies Baidu and Tencent — which operate in one of the world’s most restrictive environments — made notable improvements to their privacy and security policies over the past year.

However, Etisalat and Ooredoo made no improvements at all in this area. As we found in previous Indexes, neither company even published a privacy policy — making it impossible for users to understand what these companies do with their information, including what information they collect and for what purposes. This trend is unfortunately not that unusual for operators across the region: research conducted in 2018 by our partners at Beirut-based Social Media Exchange (SMEX) showed that just 7 out of 66 mobile operators evaluated made their privacy policies publicly available. This is despite the fact that there are no legal barriers for either company to be transparent about which user data they collect, share, their purposes for doing so, and for how long they retain that data.

Privacy scores: the 2019 RDR Index. The Privacy category of the RDR Index applies 18 indicators to evaluate how transparent companies are about policies and practices affecting users’ privacy and security, including how clearly companies disclose what types of user information they collect, share, with whom, and why.

Notably, neither company disclosed anything about their processes for responding to government demands for user data. Etisalat earned a small amount of points for disclosing that it may share the user information it collects with law enforcement or government agencies. But, like Ooredoo, the company disclosed nothing about its processes for handling such demands. Both the UAE and Qatari governments may in fact have direct access to the network and to user communications without having to request it, but internet service providers should still disclose this so that users can understand the risks of using a particular service.

Companies can still do more

While government surveillance and crackdowns on internet freedom put considerable pressure on both Etisalat and Ooredoo, the 2019 RDR Index findings demonstrate that government restrictions alone do not explain or justify such opaque company policies. Even in the absence of regulatory changes, both Etisalat and Ooredoo can take immediate steps to improve their disclosure of policies and practices affecting users’ freedom of expression and privacy.

Specifically, both companies could:

- Publish privacy policies: Both companies should publish privacy policies detailing what information they collect, share, with whom, and why — and make those policies easy to find and understand.

- Clarify content and access restrictions: Both companies should be more transparent about their processes for handling government and private requests to filter or block content or restrict user accounts, and about government requests to shut down networks.

- Improve redress: Both companies should improve their existing grievance mechanisms by explicitly including complaints related to freedom of expression and privacy, and by providing clear remedies for these types of complaints.

Click here to read the full 2019 RDR Index report.