Image by Jayanti Devi via Pixahive. CC0

Authors: Zak Rogoff, Veszna Wessenauer, Jie Zhang

From time to time, Ranking Digital Rights assesses companies that are having a growing impact on the public interest and the protection of people’s rights, but are not covered in the RDR Corporate Accountability Index. For these studies, we apply a selection of our rigorous human rights-based standards to evaluate their policies and practices, and the potential risks they pose to human rights and the global information ecosystem. As with the RDR Index, our aim with these studies is to establish an evidence base that policy makers, investors, and civil society can use to hold these companies accountable and against which we can monitor their progress over time.

This spring, Ranking Digital Rights conducted a study on the privately owned, Beijing-based company ByteDance and its twin video-sharing services TikTok and China-based counterpart Douyin. We were naturally intrigued by ByteDance, which is the first Chinese social company to achieve mass popularity outside the east Asian market, and to compete with leading U.S. platforms such as Instagram.

We set three core objectives: First, we wanted to see how ByteDance’s governance choices regarding content, data security, and government censorship and data demands affect users’ rights. Second, we wanted to compare TikTok’s and Douyin’s policies, to increase our understanding of how Chinese internet governance practices change or persist outside of Chinese territory. Finally, we wanted to find out how TikTok’s policies for U.S. users compare with the policies of its dominant U.S.-based competitors, mainly Instagram and YouTube, particularly in light of geopolitical and free speech controversies that have emerged with the rise of TikTok in the U.S.

Key questions and answers

Are TikTok’s U.S. policies substantively different from those of similar U.S.-based platforms?

No. While TikTok’s policies and practices stand out in a few small ways, the platform is largely aligned with its major competitors in the U.S. (such as Instagram and YouTube) when it comes to policies affecting users’ freedom of expression and privacy.

Are TikTok users subject to greater human rights risks, given that the platform’s parent company, ByteDance, is headquartered in China?

It’s hard to say. TikTok’s policies offer the same kinds of protections for user data as its U.S. competitors. Technical research by the Citizen Lab also suggests that the company takes technical precautions similar to those of U.S. platforms in its efforts to protect user data. TikTok says that U.S. user data is stored in the U.S. (with a backup in Singapore) and is at no risk of acquisition by the Chinese government. But we have to take TikTok’s word for it.

What does the policy contrast between TikTok (in the U.S.) and Douyin tell us about how Chinese companies operate both at home and in foreign jurisdictions?

The two platforms’ policy environments reflect critical differences in the legal and regulatory frameworks where they operate. With that being said, we observed that TikTok leverages an aggressive combination of human and algorithmic content curation and moderation techniques that appear to prioritize content that is entertaining and apolitical, similar to Douyin.

Why did we decide to study ByteDance?

Founded in 2012, ByteDance is headquartered in Beijing and legally domiciled in the Cayman Islands. It has various video sharing, social media, news, and web search products that are popular in China. Outside China, it is mostly known for its video sharing service, TikTok. For this study, we looked at two ByteDance services: TikTok and its counterpart in China, Douyin. TikTok and Douyin are both short-form video sharing platforms that share most of the same key features. They target the U.S./international and Chinese markets, respectively.

Each service has a broad user base in its target market. TikTok said in August 2020 that it had about 100 million monthly and 50 million daily active U.S. users, up nearly 800% from January 2018. According to App Annie, a mobile data and analytics company, TikTok was the most downloaded app from iOS and Android app stores in 2020, ahead of Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. Douyin hit 600 million daily active users as of August 2020, according to ByteDance.

Both Douyin and TikTok leverage the same surveillance capitalism principles of behavioral data collection and monetization that have exploded profits for Big Tech companies in the U.S. Both apps track everything from users’ locations to likes and follows to the amount of time they spend looking at specific videos in order to serve them “personalized” organic and sponsored content. Both apps also leverage the popularity of certain users (known as “creators”) to broker sponsorship deals with third-party companies that pay creators to promote their products or services to users of the app.

Our decision to evaluate ByteDance, a privately held company, marks a departure from our typical standard, which is to evaluate only publicly traded companies. As a privately held company, ByteDance has no mandate to disclose information about its corporate governance to the public, as required by major stock exchanges and regulators in most markets. This gives us fewer avenues for putting pressure on the company. Nevertheless, we believe that the large-scale human rights and public interest implications of ByteDance’s services and the exceptionally high degree of public attention on the company, due to its rapid growth and its symbolic value in the U.S.-China relations, merit our scrutiny.

TikTok has been in the political crossfire amid rising tensions between the U.S. and China, with policymakers worrying that Chinese authorities might have easy access to the data of TikTok users in the U.S. TikTok has publicly affirmed that U.S. user data is stored in the U.S. (with a backup in Singapore) and is at no risk of acquisition by the Chinese government, yet concerns about the data security of U.S. users have persisted among policymakers. Former U.S. president Donald Trump attempted to ban the app in an executive order in 2020 that was refuted by the courts and then officially reversed by President Joe Biden in June 2021. The Biden Administration put forth a new order that will set in motion “rigorous, evidence-based analysis” of certain software products owned by foreign adversaries, including China, “that may pose an unacceptable risk to U.S. national security.”

Although discussions about TikTok have been dominated by security-focused policy conversations and geopolitical concerns, particularly in the U.S. and India (where the app was banned in 2020), the service has unique qualities affecting freedom of expression and information in ways that differ from what we see on other popular platforms in the U.S. ByteDance is the first Chinese social media company to offer a social media service that is actively competing with the biggest U.S. platforms, like YouTube and Instagram. The fact that TikTok is owned by a Chinese company is important not just from a privacy standpoint, but from a content governance perspective as well.

Many experts argue that algorithmic recommendation is the main driver of the popularity of both TikTok and Douyin. For this study, we wanted to further examine this theory and assess the companies’ stance on freedom of expression, alongside privacy and security. We sought to understand the implications of the Chinese ownership of two twin services with very different target markets, demonstrate the impact of different legal and political environments on the policies and practices of these twin services, and see how they affect users’ human rights.

How did we do the research?

For this study we looked at the policies of Douyin in China, TikTok in the U.S., and parent company ByteDance. Although TikTok operates internationally and has different policies for various geographic areas, we elected to focus on its policies for the U.S. for two reasons. First, the U.S. is TikTok’s flagship overseas market, with 100 million active monthly users, and a growing group of stakeholders are investigating the platform’s policies and practices. Second, we wanted to be able to compare our findings for TikTok, and our findings for major U.S.-based social media services like Instagram and YouTube from the 2020 RDR Index, where we evaluated platforms’ policies in their home markets only.

We selected 39 of our indicators (out of the full list of 58) that would best measure the most prominent human rights risks for users of either service. Since we picked two services that pose a number of human rights risks stemming from their business models and heavy use of algorithms, we included our indicators on targeted advertising, algorithmic systems, and content governance. We also sought an empirical basis for the national security and privacy concerns that governments and the media have come to associate with TikTok. Therefore, we included our indicators assessing transparency around privacy, information security, and government demands to access user information.

We reviewed the public documents disclosed by the company, including policies provided to users and business partners, company blog posts, and reports against the criteria of each element contained in the 39 indicators selected. Each indicator comprises a set of questions (what we call “elements”) about the company’s policy or practice in a specific area. We give each service one of three possible scores for each element: “full credit” (100), “partial credit” (50), and “no disclosure found” (0) or “no credit” (0). Each service receives a per-indicator score reflecting the mean value of all elements in the indicator. Learn more about our methodology.

Alongside our indicator-based evaluation of ByteDance and its video-sharing services, we reviewed independent research of TikTok by the Citizen Lab and the Mozilla Foundation. We also reviewed independent media coverage and commentary about the company and a series of leaked internal documents from TikTok that sparked investigations by The Guardian, The Intercept, and German digital rights blog Netzpolitik.

Our research findings

We rank companies on their digital rights governance, and on their policies and practices affecting freedom of expression and privacy. Our findings are organized by these categories below. In certain cases, we compare our findings for TikTok and Douyin with our data for Instagram, from the 2020 RDR Index. Our primary objective here is to give readers an idea of how TikTok compares to one of its most prominent U.S.-based competitors.

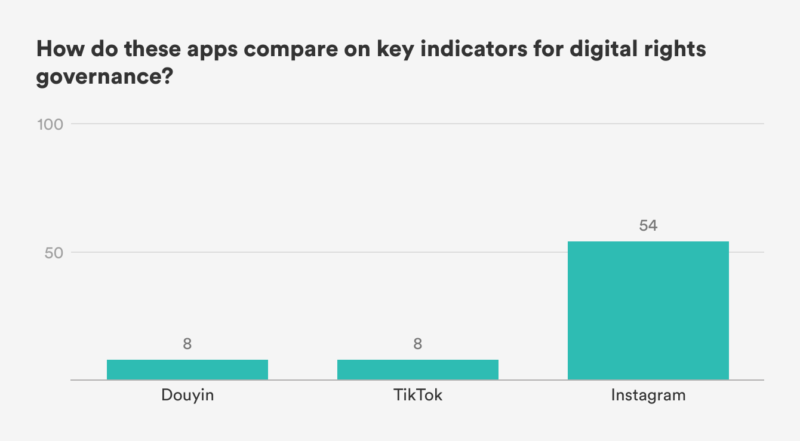

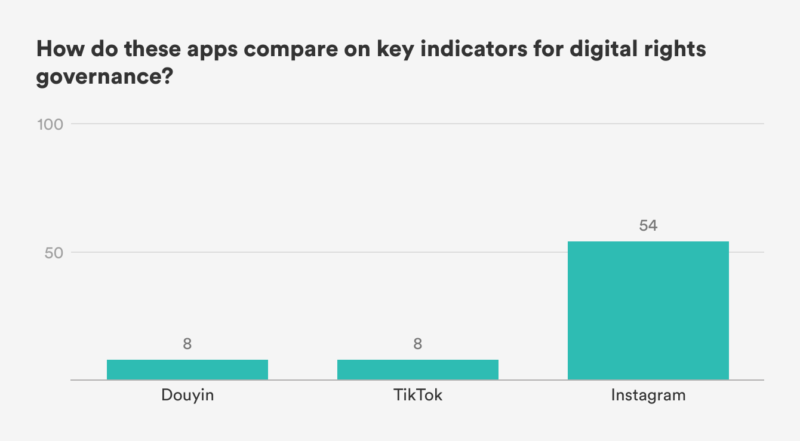

Digital rights governance

In contrast to other large multinational tech companies, ByteDance offers very little public documentation of governance policies or practices that affect people’s rights to free expression and privacy. TikTok has distinguished itself from its parent company in some policy areas that directly affect users’ rights, by doing things like publishing transparency reports, but overall, the platform does not make an explicit commitment to human rights, or conduct human rights due diligence, in accordance with our standards.

Values represent combined average indicator scores for each issue area. See appendix for more.

Neither ByteDance, nor TikTok, nor Douyin pledged to protect privacy or freedom of expression as defined by human rights law (G1), nor did either service conduct human rights impact assessments, a key tool for companies seeking to prevent their products and services from causing human rights harms (G4). This is typical of Chinese social platforms ranked by RDR, but it puts TikTok behind major U.S. peers such as Instagram (owned by Facebook), which conducts human rights impact assessments in some key areas, including its processes for policy enforcement and its approach to government regulations and policies that affect freedom of expression and information and privacy.

Content governance

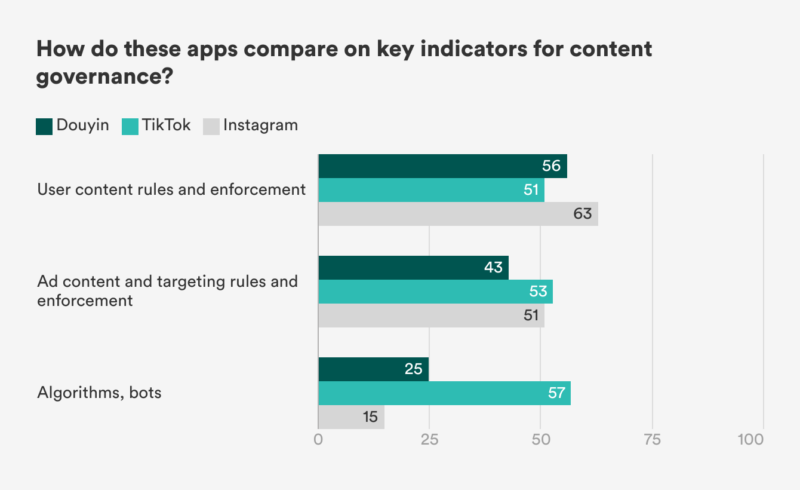

User content rules/governance and enforcement

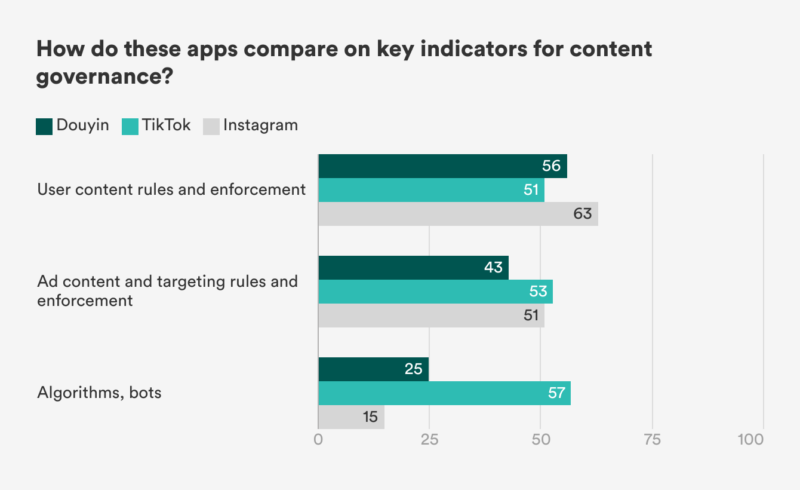

Indicators G6b, F1a, F3a, F4a, F4b

Both services provided public content rules that were easy to find and understand (F1a), though Douyin was slightly more detailed in explaining the circumstances under which it may restrict content or user accounts (F3a) and appeared to offer a more comprehensive system for users to appeal moderation decisions (G6b). Leaks have revealed that TikTok also maintains more detailed internal rules that are not visible to the public. TikTok reported more data than Douyin about the nature and volume of its enforcement actions (F4a, F4b), roughly on par with Instagram.

Values represent combined average indicator scores for each issue area. See appendix for more.

Ad content and targeting rules and enforcement

Indicators F1b, F1c, F3b, F3c, F4c

Advertising is the primary source of revenue for both ByteDance services, similar to other major platforms in China and the U.S. Whereas Douyin’s advertising policies were jumbled and hard to find, TikTok was more transparent about its ad policies and enforcement actions, narrowly surpassing Instagram’s score on this metric in the 2020 RDR Index. A Mozilla study found that the company did not fully enforce its advertising policies when it came to content sponsored (i.e., paid for) by third parties shared by TikTok influencers, a misstep for which Instagram also has been criticized. Douyin failed to provide any data about the volume and nature of its enforcement of ad content policies (F4c).

Algorithms, bots

Indicators F1d, F12, F13

Like most companies, neither service provided comprehensive rules governing their use of algorithmic systems (F1d). However, both services offered disclosures describing their algorithmic curation processes (F12), and TikTok published a dedicated document for this purpose, which scored better than any other service ranked by RDR in 2020, including YouTube and Instagram. The document explains design considerations and some of the elements of user behavior that influence the algorithm, but it is far from comprehensive. Though ByteDance’s public materials do not mention this, leaked internal documents have shown that the algorithm also takes input from TikTok staff, who assign content to different levels of algorithmic amplification. Although we were not able to find similar information about Douyin’s practices, the general similarity of the services suggests this takes place on that platform as well, and Chinese blogs have discussed the existence of such a process.

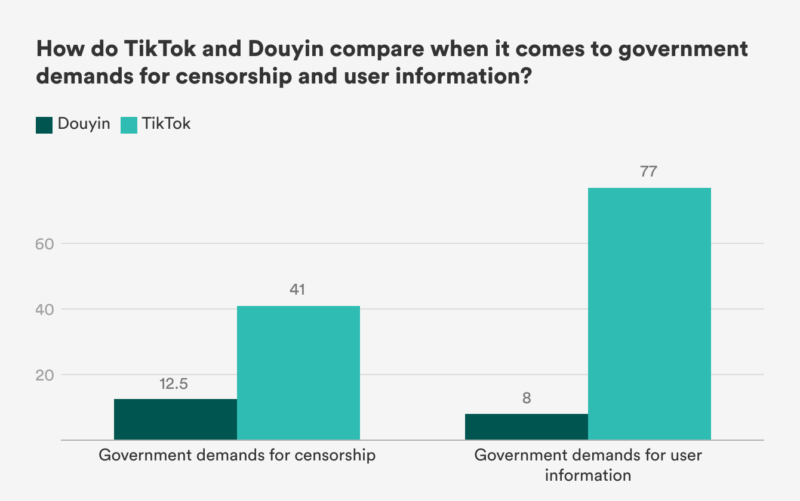

Government demands to censor content

Indicators F5a, F6, F8

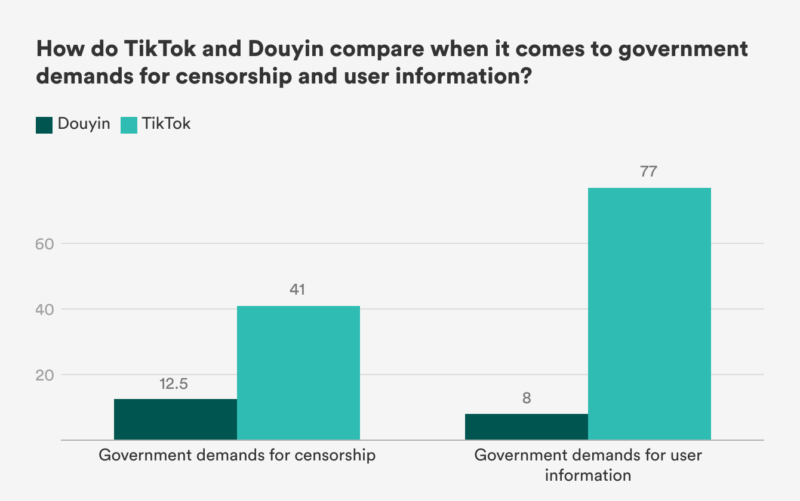

Along with government demands to access user information, government censorship demands are where we see the starkest difference between ByteDance’s two services. Unsurprisingly, this reflects China’s unique political and legal environment. Douyin discloses almost no information about its processes or data related to such demands, though a former ByteDance employee claimed they receive up to 100 per day. While it is not as clear and thorough in its disclosures as competitors such as Instagram, TikTok does regularly report on such demands, and offers this data broken out by country of origin.

Values represent combined average indicator scores for each issue area. See appendix for more.

Privacy and security

Government demands to access user information

Indicators P10a, P11a, P12

Only TikTok offered meaningful disclosure in this area. Its biannual transparency reports break out government demands for user data by country, though it is worth noting that these reports do not mention any data requests from the government of China. Douyin offers no such information. Although there are no laws or regulations in China prohibiting Chinese companies from releasing data about government demands to access user information, the political and legal environment discourages companies from doing so.

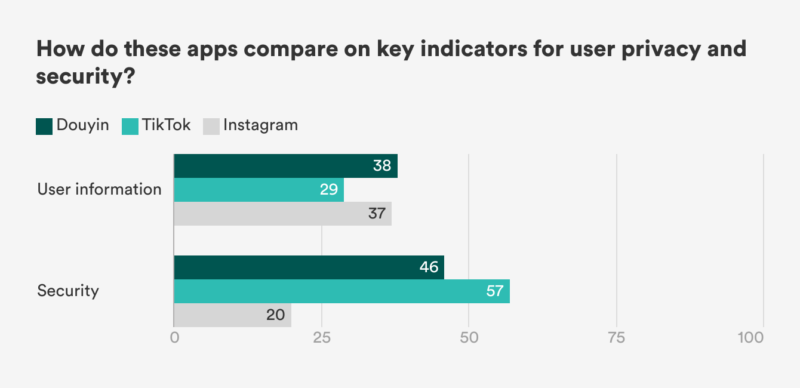

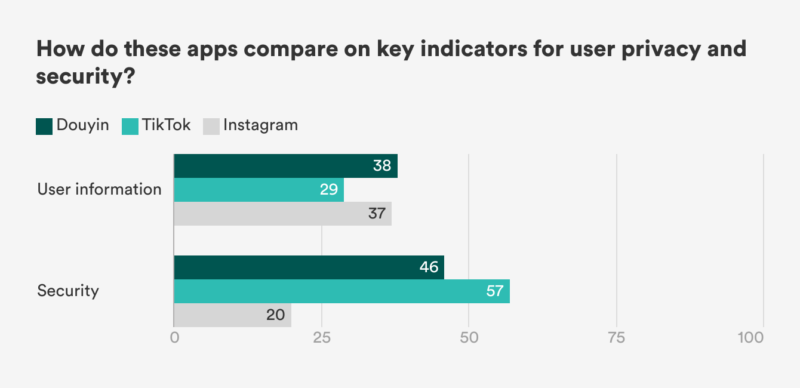

User information

Indicators P1a, P1b, P3-P9

Our data highlights the contrast between legal regimes for user data protection in China, which covers these areas with its 2017 Cybersecurity Law and a pending data protection law, and the U.S., which has no comprehensive data protection law. Douyin outperformed TikTok on our indicators for its clearer and more comprehensive disclosures of what information it collects (P3a), infers (P3b), and retains (P6), as well as its purposes for doing so (P5). Unlike TikTok, Douyin pledged to collect only data that is reasonably necessary for its functionality, as required by Chinese law, but it has been reprimanded for poor compliance with these requirements. A technical analysis by the Citizen Lab found no discrepancies between what the two apps’ privacy policies say and what information their systems actually collect. Despite its overall advantage in this area, Douyin provided fewer options for users to access (P8) or control the use of (P7) their information than TikTok.

Values represent combined average indicator scores for each issue area. See appendix for more.

Security

Indicators P13-P17

While TikTok has no published policy regarding data breaches, Douyin received a perfect score for pledging to notify users and help them navigate the consequences of such information leaks (P15), in accordance with China’s cybersecurity law. Nevertheless, TikTok outperformed Douyin on security-related indicators, largely because it offered multi-factor authentication to protect users’ accounts (P17) and made it much easier for external researchers to submit reports of security vulnerabilities (P14). Douyin has a bug-bounty program, but does not provide multi-factor authentication.

Download the complete data set, or get in touch!

We invite you to download our full dataset [.XLSX / .CSV] and find your own insights! This includes extensive excerpts from the two services’ public disclosures, analysis of their alignment with RDR’s rigorous human rights indicators, and a complete list of our sources. Contact us at info [at] rankingdigitalrights.org with questions about the analysis or data collection.

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Our indicators

For this study, we selected 39 of our indicators (from the full list of 58) that would best measure the most prominent human rights risks for users of either service.

G: Digital rights governance

F: Freedom of expression

P: Privacy

Appendix B: Indicator Groups

Each of our charts shows aggregate scores for indicator groups listed below. Each aggregate score represents the average of scores for each indicator in the group.

- Rules enforcement: G6b, F1a, F3a, F4a, F4b

- Ad rules enforcement: F1b, F1c, F3b, F3c, F4c

- Algorithms, bots: F1d, F12, F13

- Government censorship demands: F5a, F6, F8

- User information: P1a, P1b, P3-P9

- Security indicators: P13-P17

- Government demands for user information: P10a, P11a, P12

C. Sources list

In addition to conducting our own research, drawing on policies and other documents published by ByteDance, Douyin, and TikTok, we also relied on the work of other organizations that have studied and investigated TikTok and Douyin.

- Pellaeon Lin, “TikTok vs Douyin: A Security and Privacy Analysis, The Citizen Lab, March 22, 2021.

- “TikTok’s political ad policies are easy to evade”, Mozilla Foundation, June, 2021.

- Alex Hern, “Revealed: how TikTok censors videos that do not please Beijing”, The Guardian, September 25, 2019.

- Sam Biddle, Paulo Victor Ribeiro, Tatiana Dias, “INVISIBLE CENSORSHIP: TikTok Told Moderators to Suppress Posts by “Ugly” People and the Poor to Attract New Users”, The Intercept, March 16, 2020.

- Markus Reuter, Chris Köver, “TikTok: Cheerfulness and censorship”, Netzpolitik, November 23, 2019.

- Shelly Banjo, Shawn Wen, “The TikTok story”, Foundering podcast via Bloomberg, April-May, 2021.

- “TikTok Without Filters”, supporting documents for an investigation of TikTok by the European Consumer Organisation (BEUC), February, 2021.

- Jen Patja Howell, Evelyn Douek, Quinta Jurecic, “A TikTok Tick Tock”, The Lawfare Podcast, June 17, 2021.

- Matt Perault, Samm Sacks, “A Sharper, Shrewder U.S. Policy for Chinese Tech Firms”, Foreign Affairs, February 19, 2021.