Posted at 15:52h

in

Featured,

News

by Jenni Olson

In this conversation, RDR’s Global Partnerships Manager Leandro Ucciferri and Senior Editor Sophia Crabbe-Field speak with Jenni Olson, the Senior Director of Social Media Safety at GLAAD, the national LGBTQ media advocacy organization, which campaigns on behalf of LGBTQ people in film, television, and print journalism, as well as other forms of media.

GLAAD recently expanded their advocacy to protect LGBTQ rights online by holding social media companies accountable through their Social Media Safety Program. As part of this work, Jenni has helped lead the creation, since 2021, of a yearly Social Media Safety Index (SMSI), which reports on LGBTQ social media safety across five major platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok).

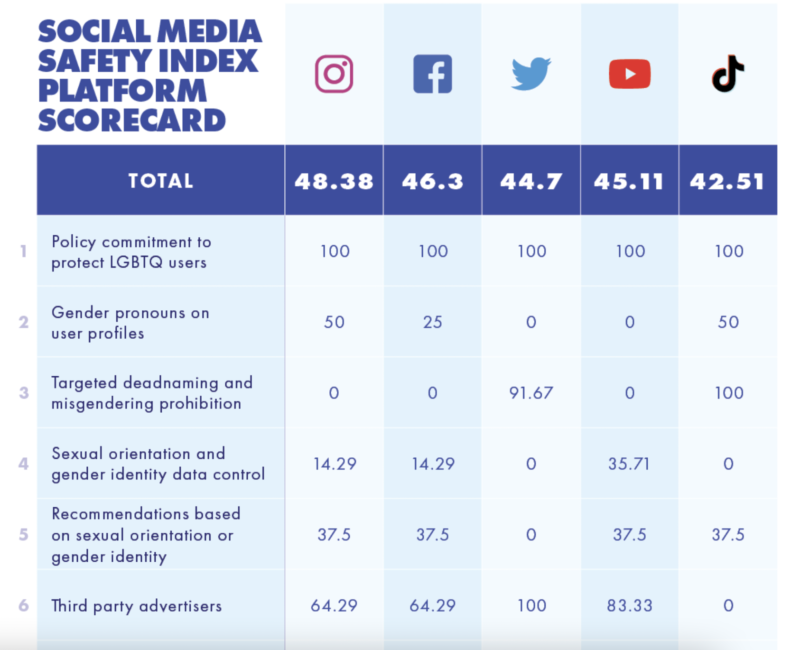

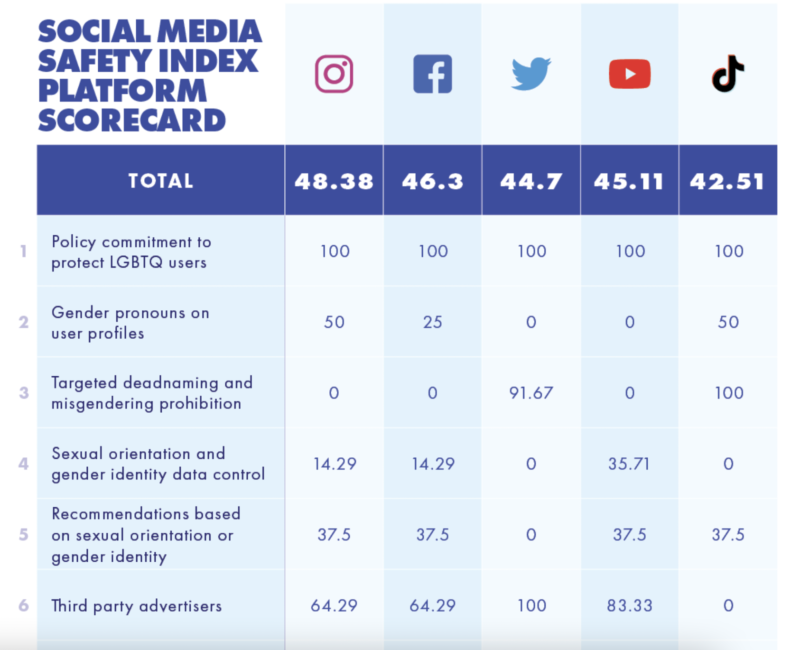

The 2022 version of the SMSI, released in July, included a Platform Scorecard developed by GLAAD in partnership with RDR, as well as Goodwin Simon Strategic Research. The Scorecard uses 12 LGBTQ-specific indicators to rate the performance of these five platforms on LGBTQ safety, privacy, and expression. (GLAAD also created a Research Guidance for future researchers interested in using their indicators.)

The main problems identified by the scorecard and SMSI include: inadequate content moderation and enforcement, harmful algorithms, and a lack of transparency, all of which disproportionately hurt LGBTQ people and other marginalized groups. The release of the 2022 SMSI in July brought widespread media attention, including in Forbes and Adweek. At the beginning of August, the project’s lead researcher Andrea Hackl wrote for RDR about her experience adapting our indicators to track companies’ commitments to policies protecting LGBTQ users.

The following conversation with Jenni touches upon the growth of politically motivated hate and disinformation, how GLAAD tailored RDR’s methodology to review the online experience of the LGBTQ community, the glaring lack of transparency from social media companies, and, following the report’s release, what’s next in the fight for LGBTQ rights online. They spoke on August 25, 2022.

Leandro Ucciferri: Thanks so much for being here with us today. We’re really happy to have you. To start off, we wanted to ask you: Why is tackling the role of social media platforms so important in the fight for LGBTQ rights?

Jenni Olson: I think that clearly social media platforms are so dominant and so important in how we as a society are getting our information and are understanding or not understanding things. The problem of misinformation and disinformation⸺as I always say, another word for that is simply “lies”⸺is really a terrible problem and we find, in our work, that hate and disinformation online about LGBTQ people are really predominant. Obviously we also have things like COVID-related misinformation and monkeypox-related misinfo (which intersects very strongly with anti-LGBTQ hate and misinfo). There’s so much politically motivated misinformation and disinformation especially about LGBT folks, and especially about trans folks and trans youth. We as a community are being targeted and scapegoated. Right-wing media and right-wing politicians are perpetuating horrible hate and disinformation. These have escalated into calls for attacks on our rights, and even physical attacks.

Just in the last couple of months, the Patriot Front showed up at Idaho Pride, the Proud Boys showed up at Drag Queen Story Hour events at public libraries, there have been arsons on gay bars, etc. So much of the hateful anti-LGBT rhetoric and narratives that have led up to these attacks has been perpetuated on social media platforms.

It’s important to note that we also have these political figures and “media figures,” pundits, who are perpetuating hate and extremist ideas for political purposes, but also for profit. One of the things we see is this grift of, “Oh, here’s all of this hate and these conspiracy theories” that then ends with, “Hey, come subscribe to the channel to get more of this.” These figures are making money, but the even more horrible thing is that the platforms themselves are also profiting from this hate. So the platforms have an inherent conflict of interest when it comes to our requests for them to mitigate that content. Which is frustrating to say the least.

Sophia Crabbe-Field: How much have you seen these trends and this rhetoric amplified in recent years? And was that a motivation for launching the Social Media Safety Index and, more recently, the scorecard?

JO: Things are so bad and getting worse. Right-wing media and pundits just continue to find new and different ways of spreading hateful messages. We did the first Social Media Safety Index last year, in 2021. The idea was to establish a baseline and to look at five platforms to determine what the current state of affairs is and say, “Okay, here’s some guidance, here are some recommendations.” Our other colleagues working in this field make many of the same basic recommendations, even if it’s for different identity-based groups, or different historically marginalized groups; we’re all being targeted in corollary ways. So, for instance, our guidance emphasizes things like fixing algorithms to stop promoting hate and disinfo, improving content moderation (including moderation across all languages and regions), stepping up with real transparency about moderation practices, working with researchers, respecting data privacy—these are things that can make social media platforms safer and better for all of us.

So we did this general guidance and these recommendations, and then met with the platforms. We do have regular ongoing meetings throughout the year on kind of a rapid-response basis; we alert them to things as they come up. They’re all different but some of them ask for our guidance or input on different features or different functionalities of their products. So we thought that for the second edition of the report in 2022, we’ll do scorecards and see how the companies did at implementing our 2021 guidance and, at the same time, we’ll have a more rigorous numeric rating of a set of elements.

What we end up hearing the most about is hate speech, but it’s important to note that LGBTQ people are also disproportionately impacted by censorship.

LU: You came up with your own very specific set of indicators, but inspired by our methodology. Why did you choose to base yourself off of RDR’s methodology and how would you explain the thought process beyond the adaptation?

JO: We had been thinking about doing a scorecard and trying to decide how to go about that. We knew that we wanted to lean on someone with greater expertise. We looked to Ranking Digital Rights as an organization that is so well respected in the field. We wanted to do things in a rigorous way. We connected with RDR and you guys were so generous and amenable about partnering. RDR then connected us with Goodwin Simon Strategic Research, with Andrea Hackl (a former research analyst with RDR) as the lead research analyst for the project. That was such an amazing process and, yes, a lot of work. With Andrea, we went about developing the 12 unique LGBT-specific indicators and then Andrea attended some meetings with leaders at the intersection of LGBT, tech, and platform accountability and honed those indicators a little more and then dug into the research. For our purposes, the scorecard seemed like a really powerful way to illustrate the issues with the platforms and have them measured in a quantifiable way.

Though it’s called the “Social Media Safety Index,” we’re looking not only at safety, but also at privacy and freedom of expression. We developed our indicators by looking at a couple of buckets. The first being hate and harassment policies: Are LGBTQ users protected from hate and harassment? The second area was around privacy, including data privacy. What user controls around data privacy are in place? How are we being targeted with advertising or algorithms? Then the last bucket would be self-expression in terms of how we are, at times, disproportionately censored. Finally, there is also an indicator around user pronouns: Is there a unique pronoun field? Due to lack of transparency, we can’t objectively measure enforcement.

A clip from the 2022 GLAAD Social Media Safety Index Scorecard.

What we end up hearing the most about is hate speech, but it’s important to note that LGBTQ people are also disproportionately impacted by censorship. We’re not telling the platforms to take everything down. We’re simply asking them to enforce the rules they already have in place to protect LGBTQ people from hate.

One thing about self-expression: There’s a case right now at the Oversight Board related to Instagram that we just submitted our public comment on. A trans and non-binary couple had posted photos that were taken down “in error” or “unjustly”⸺they shouldn’t have been taken down. That’s an example of disproportionate censorship. And that relates back to another one of the indicators: training of content moderators. Are content moderators trained in understanding LGBTQ issues? And the corresponding recommendations we’ve made are that they should make sure to train their content moderators on LGBTQ-specific issues, they should have an LGBTQ policy lead, and so on.

SC-F: When you were putting together the indicators, were you thinking about the experience of the individual user or were you also thinking more so or equally about addressing broader trends that social media platforms perpetuate, including general anti-LGBTQ violence?

JO: I would say it’s a combination of both. The end goal is our vision of social media as a safe and positive experience for everyone, especially those from historically marginalized groups. I think it’s so important to state this vision, to say that it could be like this, it should be like this.

One of the things that we really leaned in on is the policy that Twitter established in 2018 recognizing that targeted misgendering and deadnaming of trans and non-binary people is a form of anti-LGBT and anti-trans hate. It is a really significant enforcement mechanism for them. And so in last year’s report we said everyone should follow the lead of Twitter and add an explicit protection as part of their hate speech policies. We met with TikTok following last year’s SMSI release and, in March of 2021, they added that to their policy as well. This was really great to see and significant when it comes down to enforcement. We continue to press Meta and YouTube on this. Just to be clear, targeted misgendering and deadnaming isn’t when someone accidentally uses someone’s incorrect pronouns. This is about targeted misgendering and deadnaming, which is not only very vicious, but also very popular.

SC-F: Did your research have any focus on policies that affect public-facing figures, in addition to policies geared toward the general user?

JO: In fact, over the last approximately 6-9 months, targeted misgendering and deadnaming has become pretty much the most popular form of anti-trans hate on social media and many of the most prominent anti-LGBTQ figures are really leaning into it.

Some particularly striking examples of its targets include Admiral Rachel Levine, a transgender woman who’s the United States Assistant Secretary for Health. There’s also Lia Thomas, the NCAA swimmer and Amy Schneider, who was recently a champion on Jeopardy. Admiral Levine has been on the receiving end of attacks from the Attorney General of Texas Ken Paxton, as well as from Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene. Most recently, Jordan Peterson, the right-wing extremist, attacked Elliot Page on Twitter, again using malicious targeted misgendering and deadnaming.

Platforms all have different policies related to public figures. In the Jordan Peterson example, Twitter took that down because it’s considered violative of their policy. But the YouTube video where he misgenders and deadnames Elliot Page like 30 times has more than 3 million views. And he’s expressing intense animosity toward trans people. YouTube did at least demonetize that video, as well as another Peterson video which expressed similar anti-trans views and outrageously described gender-affirming care (which is recognized as the standard of care by every major medical association in the U.S.) as “Nazi medical experiment-level wrong.” But they did not take the videos down despite their stated policy of removing content that attacks people based on their gender identity. So we continue to fight on these fronts that are about protecting individual people and the community in general.

If you look at TikTok and you look at Jordan Peterson’s channel on TikTok it’s like he’s a different person (than on YouTube, for example) because TikTok just has a very low threshold for that kind of garbage.

LU: Were there any unexpected or surprising findings to come out of this year’s research? Especially when we look at the differences in policies between various companies in addressing some of the above-mentioned issues?

JO: We were already pretty familiar with what the different policies are. The issue centers around enforcement and around the company culture or attitude toward enforcement. I think that the most surprising thing to me was actually that all the companies got such low ratings. I expected them not to do well. We know from anecdotal experience that they are failing us on many fronts, but I was really actually surprised at how low their ratings were, that none of them got above a 50 on a scale of 100.

Next year we’ll have new, additional indicators. I think there are some things that aren’t totally captured by the scorecard, but I’m not sure how to capture them. For instance, here’s an anecdotal observation that’s interesting to note about the difference between TikTok and the other platforms. (By the way, sometimes I’ll say a nice thing about one of the platforms and it’s not like I’m saying they’re so great or they’re better than everyone else, there are some things that some are better at, but they all failed and they all need to do better.) If you look at TikTok and you look at Jordan Peterson’s channel on TikTok it’s like he’s a different person (than on YouTube, for example) because TikTok just has a very low threshold for that kind of garbage. It’s clear that TikTok has said, “No you can’t say that stuff.” They’re monitoring the channel in such a way where it’s just not allowed. And, again anecdotally, it feels like Meta and YouTube have a much higher threshold for taking something down. There are nuances to these things. As LGBTQ people, we also don’t want platforms over-policing us.

LU: How hopeful are you that companies will do what needs to be done to create a safer environment given all the incentives they have not to?

JO: We do this work as a civil society organization and we’re basically saying to these companies: “Hey, you guys, would you please voluntarily do better?” But we don’t have power so the other thing that we’re doing is saying there needs to be some kind of regulatory solution. But, ultimately, there needs to be accountability to make these companies create safer products. Dr. Joan Donovan at the Shorenstein Center has a great piece that I often think about that talks about regulation of the tobacco industry in the 1970s and compares it with the tech industry today, looking at these parallels with how other industries are regulated and how there are consequences if you have an unsafe product. If the Environmental Protection Agency says, “You dumped toxic waste into the river from your industry, you have to pay a $1 billion fine for that,” well then the industry will say, “Okay, we’ll figure out a solution to that, we won’t do that because it’s going to cost us a billion dollars.” The industry is forced to absorb those costs. But, currently, social media and tech in general is woefully under-regulated and we, as a society, are absorbing those costs. Yes, these are very difficult things to solve but the burden has to be on the platforms, on the industry, to solve them. They’re multi-billion dollar industries, yet we’re the ones absorbing those costs.

It’s not like the government is going to tell them: “You can say this and you can’t say that.” That’s not what we’re saying. We’re saying that there has to be some kind of oversight. It’s been interesting to see the DSA [the European Digital Services Act] and to see things happening all over the world that are going to continue to create an absolute nightmare for the companies and they are being forced to deal with that.

Social media and tech in general is woefully under-regulated and we, as a society, are absorbing those costs. Yes, these are very difficult things to solve but the burden has to be on the platforms to solve them.

SC-F: You’ve already touched on the difficulty of measuring enforcement because of the lack of transparency, but from what you’re able to tell, at least anecdotally, do you see a wide schism between the commitments that are made and what plays out in the real-life practices of these companies?

JO: I have two things to say about that. Yes, we have incredible frustration with inadequate enforcement, including things that are just totally blatant, like the example I just mentioned of YouTube with the Jordan Peterson videos. It was an interesting thing to feel like, on the one hand, it’s a huge achievement that YouTube demonetized those two videos, which means they are saying this content is violative. But it’s extremely frustrating that they will not actually remove the videos. In YouTube’s official statement in response to the release of the SMSI they told NBC News: “It’s against our policies to promote violence or hatred against members of the LGBTQ+ community.” Which quite frankly just feels totally dishonest of them to assert when they are allowing such hateful anti-LGBTQ content to remain active. They say they’re protecting us, but this is blatant evidence that they are not. As a community we need to stand up against the kind of hate being perpetuated by people like Jordan Peterson, but even more so we should be absolutely furious with companies like YouTube that facilitate that hate and derive enormous profits from it.

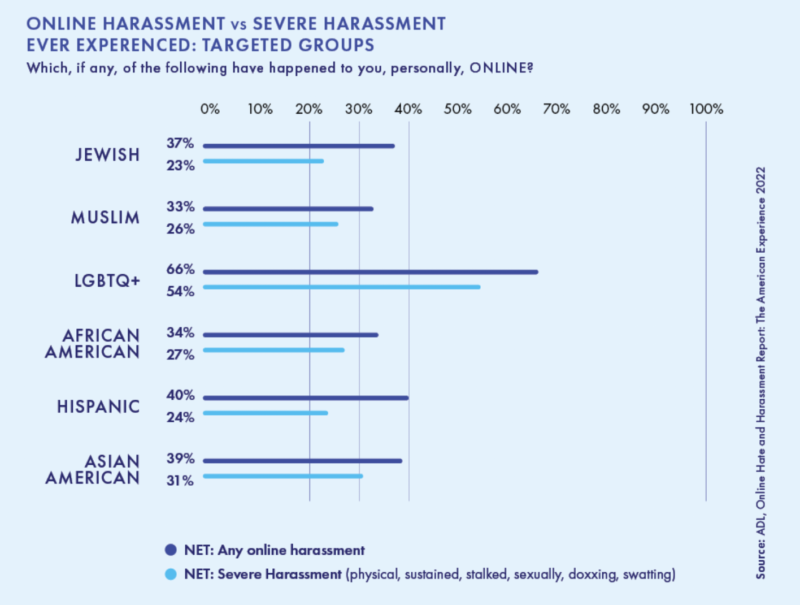

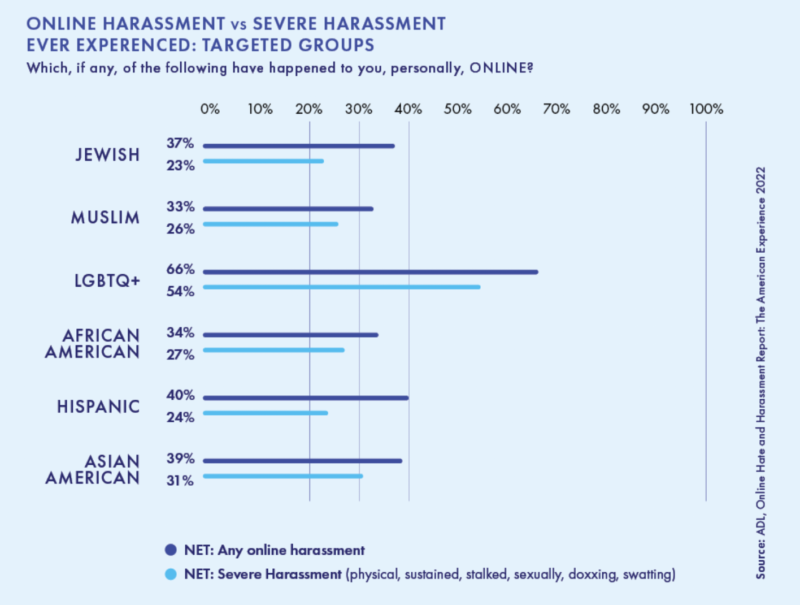

Source: GLAAD’s 2022 Social Media Safety Index.

In addition to our advocacy efforts pressing the platforms on their policies there are many other modes of activism we’re trying to be supportive of. The folks at Muslim Advocates have launched a lawsuit against Meta based on the concept of Facebook engaging in false advertising. Meta says that their platforms are safe, that their products are safe, but they’re not. I think it’s being referred to as an “experimental lawsuit.” It’s exciting to me that there are different kinds of approaches to this issue that are being tried out. Another approach is shareholder advocacy, there’s exciting stuff there. There are also things like No Hate at Amazon, an employee group opposing all forms of hate within the company, which actually did a die-in a couple months ago over the company’s sale of anti-trans books.

SC-F: Do you feel at all hopeful that the scorecard might lead to more transparency that would, eventually, allow for better monitoring of enforcement?

JO: I’m not naïve enough to believe that the companies are just going to read our recommendations and say “Oh wow, thank you, we had no idea, we’ll get right on that, problem solved, we’re all going home.” This kind of work is what GLAAD has done since 1985: create public awareness and public pressure and maintain this public awareness and call attention to how these companies need to do better. There are times when it feels so bad and feels so despairing like, “Oh, we had this little tiny victory but everything else feels like such a disaster.” But then I remind myself: This is why this work is so important. We do have small achievements and we have to imagine what it would be like, how much worse things would be, if we weren’t doing the work. I’m not naïve that this is going to create solutions in simple ways. It is a multifaceted strategy and, as I mentioned a minute ago, it is also really important that we’re working in coalition with so many other civil society groups, including with Ranking Digital Rights. It’s about creating visibility, creating accountability, and creating tools and data out of this that other organizations and entities can use. A lot of people have said, “We’re using your report, it’s valuable to our work.” In the same way that last year we pointed to RDR’s report in our 2021 SMSI report.

A lot of people have said, “We’re using your report, it’s valuable to our work.” In the same way that last year GLAAD pointed to RDR’s report in our 2021 SMSI report.

LU: That’s great. You had this huge impact already with TikTok this past year. In our experience as well, change is slow. But you’re moving the machinery within these companies. Tied to that, and to the impact you’re making with the SMSI, I think our last question for today would be: How do you envision the SMSI being used? Because, on one hand, GLAAD is doing their own advocacy, their own campaigning, but at the same time you’re putting this out there for others to use. Do you hope that the LGBTQ community and end users will use this data on their own? Do you expect that more community leaders and advocates in the field will use this information for their own advocacy? How do you see that playing out in the coming months and complementing the work GLAAD is doing?

JO: Thanks for saying that we’ve done good work.

One of the amazing things about the report is that it came out about three, four weeks ago, and we got incredible press coverage for it. And that’s just so much of a component: public awareness and people understanding that this is all such an enormous problem. But also building public awareness in the LGBTQ community. Individual activists and other colleagues being able to cite our work is very important: cite our numbers, cite the actual recommendations, cite the achievements.

It does feel really important that GLAAD took leadership on this. I was brought on two years ago as a consultant on the first Social Media Safety Index and we saw that this work was not being done. That was the first ever “Okay, let’s look at this situation and establish this baseline and state that this is obviously a problem, and here’s the big report.”

But at the same time, I just have a lot of humility because there are so many people doing this work. There are so many individual activists that inspire me, it’s so moving. Do you know who Keffals is? She’s a trans woman, a Twitch streamer in Canada. She does such amazing activism, such amazing work — especially standing up as a trans activist online and on social media, and just this past weekend she was swatted. Swatting is when someone maliciously calls the police and basically reports a false situation to trigger a SWAT team being sent to a person’s house. So they showed up at her house and busted down her door and put a shotgun in her face, terrifying her and taking her stuff and taking her to jail; it’s just horrifying. And, like doxing, it’s another common and terrible form of anti-LGBTQ hate unique to the online world which manifests in real-world harms. She just started talking about this yesterday and it’s all over the media. She’s putting herself on the line in this way and being so viciously attacked by anti-trans extremists Anyway, it’s so powerful for people like her to be out there, courageously being who they are, and they deserve to be safe. I’m grateful that we get to do this work as an organization and that it’s useful to others. And I’m just humbled by the work of so many activists all over the world.

If you’re a researcher or advocate interested in learning more about our methodology, our team would love to talk to you! Write to us at partnerships@rankingdigitalrights.org.